All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The lupus Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lupus Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lupus and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lupus Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported through a founding grant from AstraZeneca. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lupus content recommended for you

Editorial theme | Health-related quality-of-life in adolescent-onset and adult-onset SLE

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is associated with poor quality of life (QoL) when compared with rheumatic disease and the general population.1 Symptoms including rash, arthritis, and lupus nephritis can impact patients’ QoL and reduce survival.

Childhood-onset SLE now has a 10-year survival rate of more than 90%; however, these patients often experience worse outcomes and a higher mortality rate compared with adult-onset SLE. It is unclear if QoL is different in patients with adolescent-onset compared with adult-onset SLE. Here, we report data from the longitudinal LUMINA study examining the differences in QoL for patients with adolescent- and adult-onset SLE.1 This is the first article in our editorial theme on QoL in patients with lupus.

Study design1

Patients were selected from the LUMINA database, a multiethnic cohort of 640 patients with SLE from Texas, Alabama, and Puerto Rico, with a total of 95 and 375 patients with adolescent- and adult-onset SLE included in the study, respectively. Data were collected at baseline, Month 6, Month 12, and then yearly. The primary outcome measure was a 36-item self-reported survey (SF-36) which measured health-related QoL (HR-QoL). Answers were used to calculate a physical-component summary score (PCS) and mental-component summary score (MCS) for patients, with scores ranging from lack of function (score 0) to full function (score 100). HR-QoL was evaluated for adolescent- versus adult-onset SLE, considering sociodemographic variables, behavioral features, and co-morbidities.

Patient characteristics1

Patient characteristics for both groups at baseline, including sociodemographic and behavioral features, are shown in Table 1. For the purposes of this study, patients diagnosed at ≤24 years of age were classed as adolescent-onset and patients diagnosed at ≥25 years of age were classed as adult-onset. There was no significant difference in years of formal education or household income between the groups and the most frequently reported ethnicity was African American.

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics*

|

SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus. |

|||

|

Characteristic, % (unless |

Adolescent-onset SLE |

Adult-onset SLE |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Mean age at enrollment, years |

21.6 |

41.3 |

<0.01 |

|

Mean age at diagnosis, years |

19.7 |

39.3 |

<0.01 |

|

Female |

86.3 |

91 |

0.18 |

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

Caucasian |

23.3 |

30.9 |

|

|

African American |

33.7 |

31.2 |

|

|

Hispanic† |

43.2 |

37.9 |

|

|

Mean time in formal education, |

12.8 |

3.3 |

0.2 |

|

Low household income‡ |

38.9 |

28.7 |

0.07 |

|

Smoking |

6.3 |

16.0 |

0.01 |

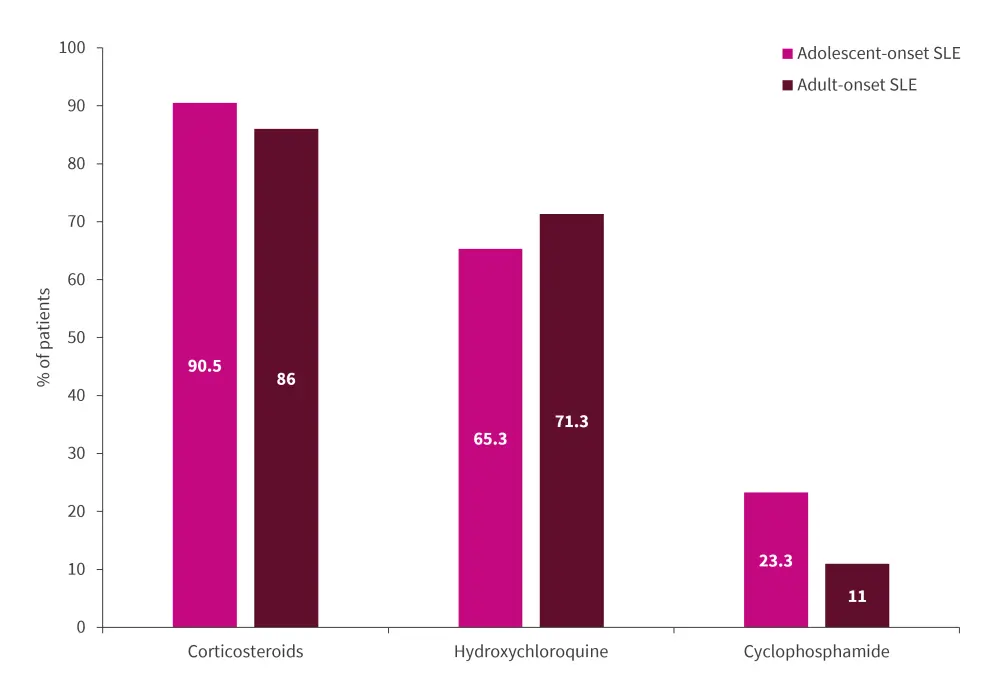

Disease features of both groups at baseline are shown in Table 2. Adolescent-onset patients had a much higher incidence of lupus nephritis, whereas neurocognitive impairment was higher in adult-onset patients; there was also significantly higher cyclophosphamide use in patients with adolescent-onset compared with adult-onset SLE (23% vs 11%; p < 0.01).1

Table 2. Disease features, clinical features, and associated treatments at baseline*

|

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; SLAM, Systemic Lupus Activity Measure; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus. ‡Significant p values (less than 0.05) |

|||

|

Features, % (unless otherwise |

Adolescent-onset SLE |

Adult-onset SLE |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Malar rash |

49.5 |

51.2 |

0.82 |

|

Arthritis |

70.5 |

78.4 |

0.13 |

|

Lupus nephritis† |

55.1 |

29.1 |

<0.01‡ |

|

Seizures/psychosis |

13.7 |

7.7 |

0.10 |

|

Neurocognitive impairment |

10.6 |

22.4 |

0.01‡ |

|

Fibromyalgia |

4.2 |

6.7 |

0.48 |

|

Dry eyes |

22.3 |

28.5 |

0.25 |

|

Dry mouth |

20.2 |

30.8 |

0.04‡ |

|

Mean number of ACR criteria, n |

5.6 |

5.3 |

0.04‡ |

|

Mean SLAM score, n |

9.5 |

8.6 |

0.15 |

|

Anti-dsDNA antibodies |

75 |

53.1 |

<0.01‡ |

Medications taken by patients at baseline are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Medication use at baseline*

SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

*Adapted from Borgia et al.1

SF-36 scores in adolescent-onset SLE vs adult-onset SLE1

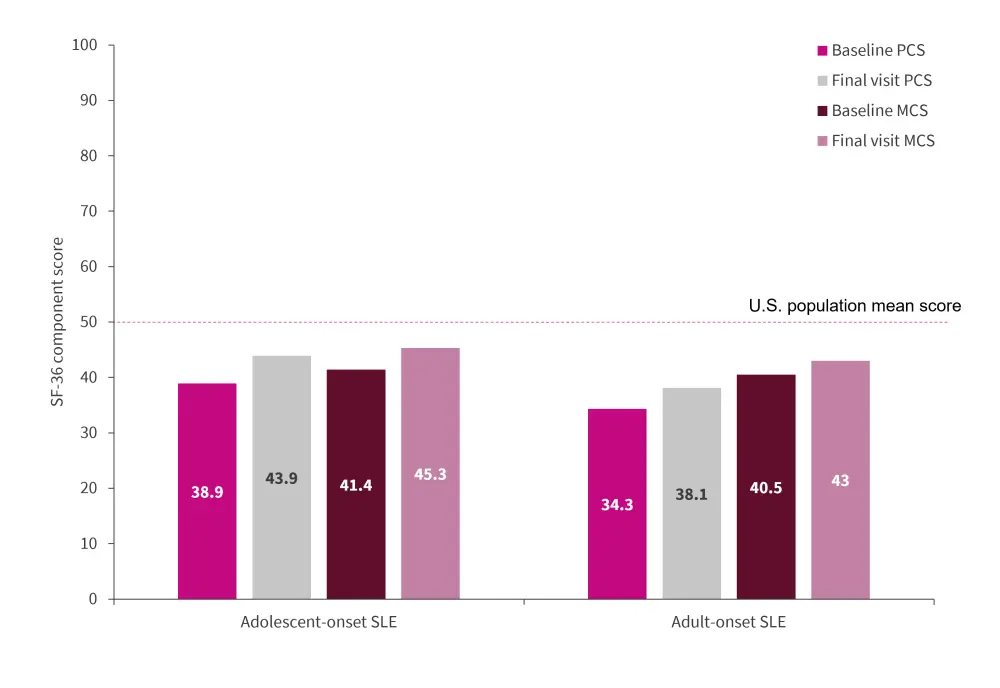

Both groups showed improvement in PCS and MCS scores from baseline to final visit (Figure 2). Minimal clinically important differences were defined as an increase of at least 2.1 for PCS and 2.4 for MCS. Both PCS and MCS scores for both groups showed minimal clinically important differences but remained below the general United States population mean score of 50.

Figure 2. Baseline and final visit PCS and MCS scores*

MCS, mental component summary score; PCS, physical component summary score; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; U.S; United States.

*Adapted from Borgia et al.1

Conclusion1

The only significant difference in medication use between groups was cyclophosphamide, which was higher for adolescent-onset patients; this is suggestive of more severe disease. In addition, adolescent patients met a higher number of American College of Rheumatology criteria at baseline than adult-onset patients, again indicating increased disease severity. Despite adolescent-onset patients experiencing more severe disease, they exhibited better physical functioning at baseline and at final visit compared with adult-onset patients.

Based on these findings, Borgia et al.1 postulate that younger patients with SLE may find adjustment to chronic disease easier compared to adult patients, translating into a higher self-reported PCS score. Despite there being no statistically significant trends in HR-QoL, there were clinically meaningful improvements in both PCS and MCS for both groups; this may be due to improved coping mechanisms. However, the authors were unable to assess whether PCS would decline beyond the 5-year follow-up as seen in similar studies. With this being the first longitudinal study comparing HR-QoL in adolescent- and adult-onset SLE, further studies of larger cohorts are warranted to elucidate the links between age and QoL.

Limitations of the study included the presence of unknown and unmeasured factors that affected HR-QoL. Moreover, the trends in HR-QoL were not shown to be statistically significant and no link could be established with time dependent variables. Borgia et al.1 concluded that the findings provide a clearer understanding of HR-QoL in adolescent and adult patients, highlighting the need for patient-centered approaches and interventions to improve HR-QoL for patients with SLE across age groups.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content