All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The lupus Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lupus Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lupus and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lupus Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported through a founding grant from AstraZeneca. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lupus content recommended for you

Incidence of serious infections in patients with SLE

Do you know... What bacterial strain is the most frequent cause of infections in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in a North Indian center?

There is a high risk of infection in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) due to the combination of immunosuppressive treatment and immune dysregulation. The prevalence of serious infectious events can range between 15% and 40%, depending on the study, with the majority being bacterial infections. Infection and disease activity remain the main causes of mortality for patients with SLE, with serious infection also predicting mortality in pediatric SLE.1

Data on the incidence of infection in patients with SLE is vital for effective treatment; however, there is a lack of data for patients in South Asia. To address this need, Aggarwal presented data on serious infection incidence and predictors of serious infection in North India at the American College of Rheumatology annual meeting (ACR Convergence 2022).1

Study design

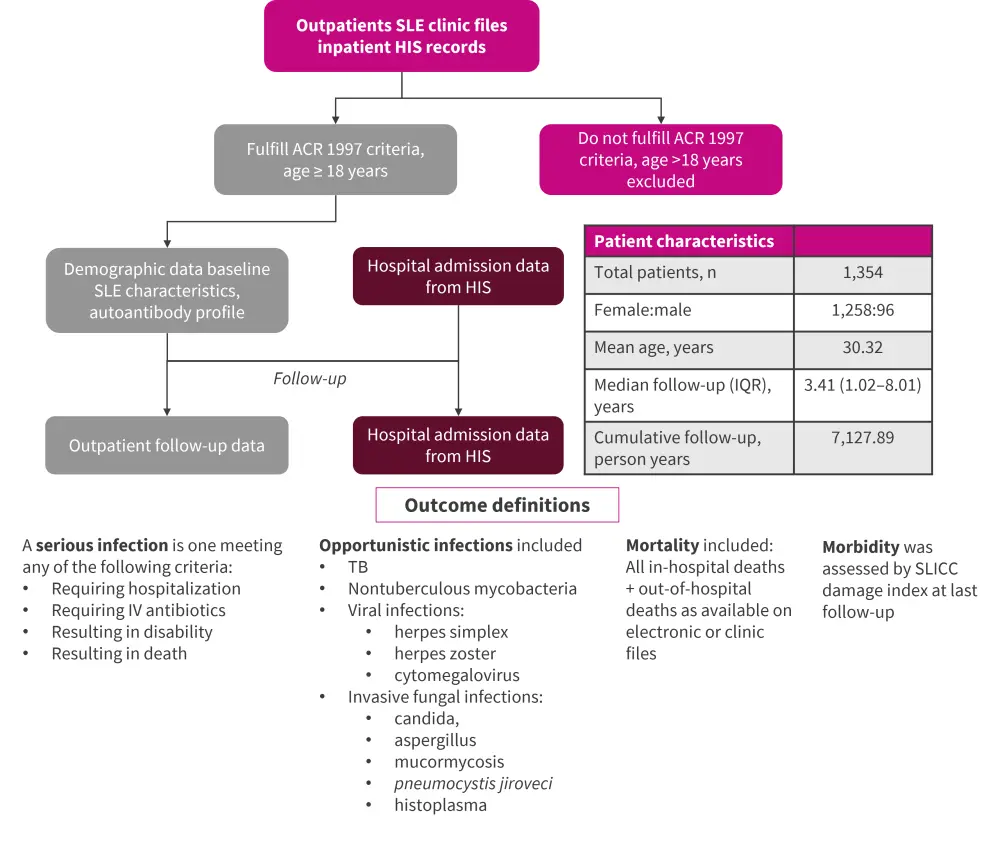

This was a single-center retrospective study conducted in North India to assess the incidence of serious infections (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study design, outcome definitions, and baseline characteristics*

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; HIS, hospital information system; IQR, interquartile range; IV, intravenous; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SLICC, Systemic lupus International Collaborating clinics; TB, tuberculous.

*Adapted from Aggarwal. et al.1

Results

In total 1,354 patients with SLE were included and the median follow-up was 3.4 years (range, 1.02–8.01 years). The most common clinical manifestations of SLE were constitutional, mucocutaneous, and arthritis; almost half of patients had nephritis (Table 1).

Table 1. Disease manifestations*

|

GI, gastrointestinal; NP, neuropsychiatric; APS, antiphospholipid syndrome. |

|

|

Features, % |

|

|---|---|

|

Constitutional |

74.2 |

|

Mucocutaneous |

69.5 |

|

Arthritis |

62.9 |

|

Myositis |

8.9 |

|

Hematological |

42.7 |

|

Serositis |

16.1 |

|

Nephritis |

48.4 |

|

NP lupus |

10.5 |

|

Cardiovascular |

3.1 |

|

Respiratory |

2.5 |

|

GI |

2.2 |

|

Vasculitis |

4.8 |

|

APS |

8.4 |

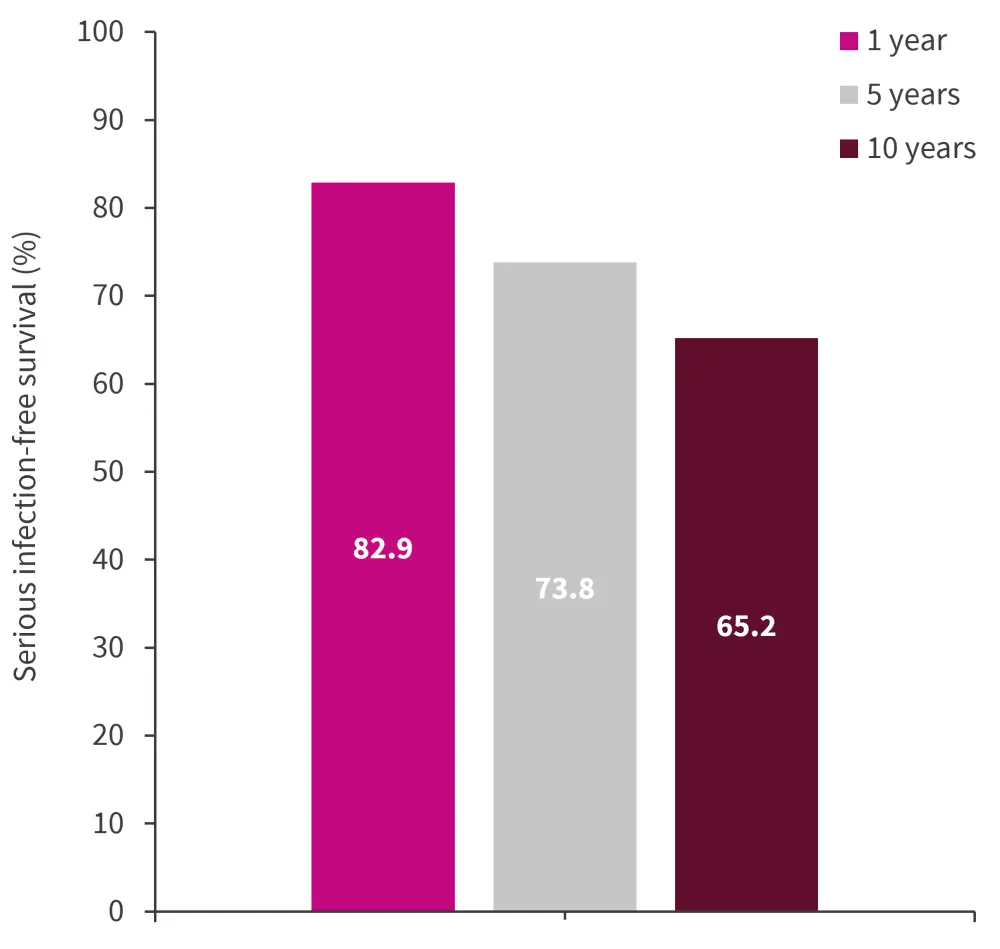

Overall, 22% of patients experienced infection during the study period, with 457 serious infectious events being recorded and 101 patients experiencing recurrent infections. The incidence rate of infections was 6.16 serious infections/100 person years. The number of infections was highest in the first year after diagnosis but then decreased at 5 and 10 years (Figure 2). Aggarwal highlighted that infection rates remained fairly similar over the last 20 years in this clinic.

Figure 2. Infection-free survival*

*Adapted from Aggarwal, et al.1

The most frequent site/type of infection were the lung, sepsis, abscess, and lower urinary tract.

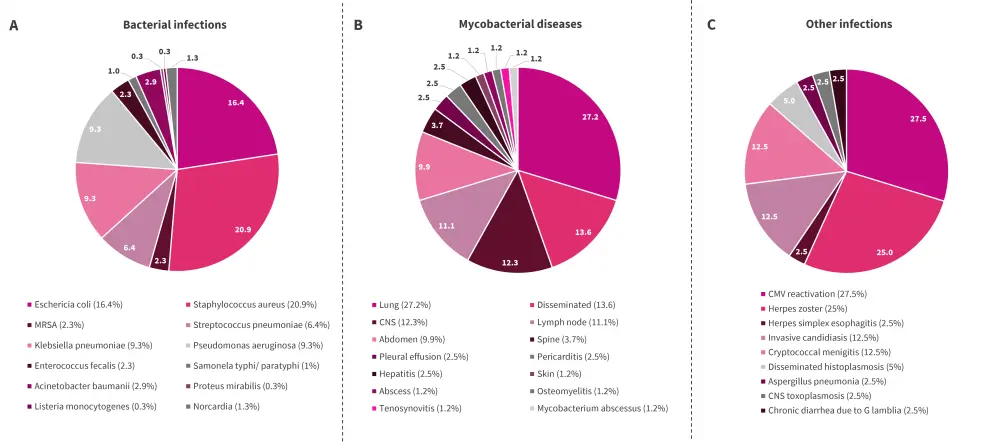

Bacterial infections were the most prevalent, making up 68% of serious infections; staphylococcus aureus, followed by E. coli, were the most common (Figure 3A). Mycobacterial diseases made up 22.7% of serious infections, of which 27.2% were in the lungs (Figure 3B). Of the 40 other infections recorded, the majority were viral and 27.5% were attributed to cytomegalovirus reactivation (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Pie charts showing A bacterial infectious agent, B locations of mycobacterial infections, and C other infections*

NS, central nervous system; CMV, cytomegalovirus; MRSA, multi drug resistant staphylococcus aureus.

*Adapted from Aggarwal, et al.1

Factors that were associated with an increased risk of serious infection included gastrointestinal manifestation of SLE and high daily steroid dose (Table 2). Model 1 (Cox proportional hazard model) investigated the first serious infection whereas model 2 (Anderson Gill modification) looked at recurrent serious infections; the same factors were significant in each group.

Table 2. Serious infection risk factors*

|

CI, cumulative incidence; HR, hazard ratio; GI, gastrointestinal; SLEDAI, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index. |

||||

|

Covariates |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HR |

95% CI |

HR |

95% CI |

|

|

GI lupus manifestation |

2.75 |

1.65–4.59 |

2.07 |

1.09–3.96 |

|

SLEDAI |

1.02 |

1.01–1.05 |

1.03 |

1.01–1.05 |

|

Daily steroid dose/10 mg |

1.65 |

1.55–1.76 |

1.43 |

1.36–1.51 |

|

Average cumulative steroid dose |

1.007 |

1.005–1.009 |

1.002 |

1.001–1.004 |

|

Albumin |

0.65 |

0.56–0.76 |

0.83 |

0.71–0.96 |

- The increase in serious infections was associated with a significant increase in the risk of mortality (p < 0.001);

- the hazard ratio increased with each increase in the number of infectious episodes experienced (Table 3); and

- patients with SLE and infection also accumulated more damage (as assessed by SDI score) than those who did not get infected.

Table 3. Multistate cox regression for mortality with each infection*

|

CI, cumulative incidence; HR, hazard ratio. |

||

|

Covariates

|

Model 3 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

HR |

95% CI |

|

|

Infection 1 |

18.2 |

11.8–28.1 |

|

Infection 1:2 |

32.7 |

16.9–63.0 |

|

Infection 2:3 |

81.6 |

29.9–222.7 |

Conclusion

Infections are a significant issue for patients with SLE, with an incidence rate of 6.16 serious infections occurring per 100 person years. The highest number of infections were recorded in the first year of disease and decreased over time. Most infections were bacterial, with lung infections seen most frequently. In India, where tuberculosis (TB) is still a major issue, patients with lupus have an increased incidence of TB compared to the rest of the population; lupus flares and extrapulmonary TB can present in a similar fashion, leading to diagnostic challenges. Aggarwal noted that questions for HCPs in this region could include “Should patients with SLE be screened for TB, and should TB prophylaxis be considered in patients undergoing intensive immunosuppressive treatment?”

Factors that associated with risk of infection included gastrointestinal manifestations of lupus, daily steroid dose, and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index score. Mortality rates increased in patients with infections compared with those without and increase with each subsequent infectious event. To overcome the limitations associated with this retrospective study, Aggarwal concluded by discussing a prospective study of 2,500 patients (INSPIRE cohort) to further elucidate the risk factors of infection for patients with Lupus in South Asia.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content