All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The lupus Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lupus Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lupus and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lupus Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported through a founding grant from AstraZeneca. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lupus content recommended for you

Links between cardiovascular disease and autoimmune disease: Results from a large-scale observational study

Certain autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis, may be used to predict the risk of cardiovascular disease in clinical practice.1 The link between cardiovascular and autoimmune disease is thought to be largely due to an increased presence of inflammatory cytokines and autoantibodies associated with the pathophysiology of these diseases.

The contribution of autoimmune diseases, interactions with other cardiovascular disease factors, and the exact mechanism underlying any increased risk, is still uncertain. Despite previous studies into select inflammatory diseases and specific cardiovascular outcomes, large-scale studies into the cardiovascular risk associated with autoimmune diseases have not been performed. This has led to a lack of evidence to inform cardiovascular prevention guidelines in autoimmunity.1

Conrad et al.1 recently published their data from a large-scale observational study in the Lancet, which evaluated multiple autoimmune disorders and the risk of multiple cardiovascular diseases. The study aimed to determine whether, and to what extent, autoimmune diseases are associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease.1 We are pleased to provide a summary of their findings here.

Study design

A patient cohort was assembled from care records from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) and the GOLD and Aurum datasets, with data taken from January 1985 to June 2019. Patients were selected if they had an autoimmune disease, were aged <80 years at diagnosis, and were free from cardiovascular events for 12 months after their diagnosis (to minimize risk of reverse causality). A matched cohort was also created, matched on calendar time (individuals contributing to data 2 years before or after matched case individuals), age, sex, socioeconomic status, and region, with up to five matched individuals per patient. The matched cohort were free from cardiovascular disease for 12 months after study entry.

Overall, the study comprised a total of 2,549,279 participants, and the autoimmune disease cohort included patients with any of the 19 most common autoimmune diseases. Patient characteristics at baseline are presented in Table 1, with an average age of 47.2 years in the autoimmune disease cohort and 47.6 years in the control cohort. The majority of individuals were white (85.9% in the autoimmune disease cohort and 83.8% in the control cohort) and female (60.8% in the autoimmune disease cohort and 61.0% in the control cohort).

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics*

|

BMI, body mass index. |

||

|

Characteristic, % (unless otherwise stated) |

Autoimmune disease cohort |

Matched control cohort |

|---|---|---|

|

Age at index date, years |

47.2 |

47.6 |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

Female |

60.8 |

61.0 |

|

Male |

39.2 |

39.0 |

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

White |

85.9 |

83.8 |

|

Other |

14.1 |

16.2 |

|

Missing data |

5.4 |

13.4 |

|

Cardiovascular prevention therapy |

|

|

|

Aspirin |

8.5 |

5.7 |

|

Statins |

19.1 |

13.1 |

|

Type 2 diabetes |

7.0 |

3.2 |

|

Systolic blood pressure |

|

|

|

Mean, mm Hg |

130 |

130 |

|

Missing data |

35.9 |

47.3 |

|

BMI |

|

|

|

Mean, kg/m3 |

27.9 |

27.1 |

|

Missing data |

59.8 |

63.2 |

The number of patients within each autoimmune disease category, plus the number of matched cohort individuals, is given in Table 2. Of note, the study included 10,483 patients with SLE matched to 49,402 control individuals.

Table 2. Patient distribution according to autoimmune disease*

|

*Adapted from Conrad, et al.1 |

||

|

Variable |

Autoimmune disease cohort |

Matched control cohort |

|---|---|---|

|

Number of autoimmune diseases |

|

|

|

1 |

404,547 |

1,902,682 |

|

2 |

37,226 |

177,676 |

|

≥3 |

4,676 |

22,472 |

|

Connective tissue diseases |

160,217 |

761,918 |

|

Ankylosing spondylitis |

9,864 |

46,121 |

|

Polymyalgia rheumatica |

48,102 |

231,802 |

|

Rheumatoid arthritis |

66,796 |

318,456 |

|

Sjögren’s syndrome |

9,933 |

47,330 |

|

Systemic lupus erythematosus |

10,483 |

49,402 |

|

Systemic sclerosis |

2,159 |

10,310 |

|

Vasculitis |

37,940 |

178,494 |

|

Organ-specific diseases |

407,078 |

1,909,992 |

|

Addison's disease |

2,548 |

12,055 |

|

Coeliac disease |

24,895 |

115,692 |

|

Type 1 diabetes |

50,264 |

235,540 |

|

Inflammatory bowel disease |

49,214 |

230,236 |

|

Graves' disease |

44,001 |

207,508 |

|

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis |

7,630 |

35,650 |

|

Multiple sclerosis |

12,006 |

56,523 |

|

Myasthenia gravis |

2,171 |

10,319 |

|

Pernicious anemia |

32,910 |

156,887 |

|

Psoriasis |

185,178 |

869,184 |

|

Primary biliary cirrhosis |

4,612 |

21,973 |

|

Vitiligo |

23,709 |

109,914 |

Cardiovascular risk in whole study population

The primary endpoint of the study was the presentation of cardiovascular disease, with 12 cardiovascular conditions evaluated. Autoimmune diseases were considered individually and combined, in addition to analyses of subgroups of connective tissue diseases and organ-specific diseases. In combined analyses for patients with multiple autoimmune diseases, the first recorded autoimmune disease was used. Similarly, risk of each cardiovascular disease was considered individually and as a composite outcome of all 12 cardiovascular diseases included.

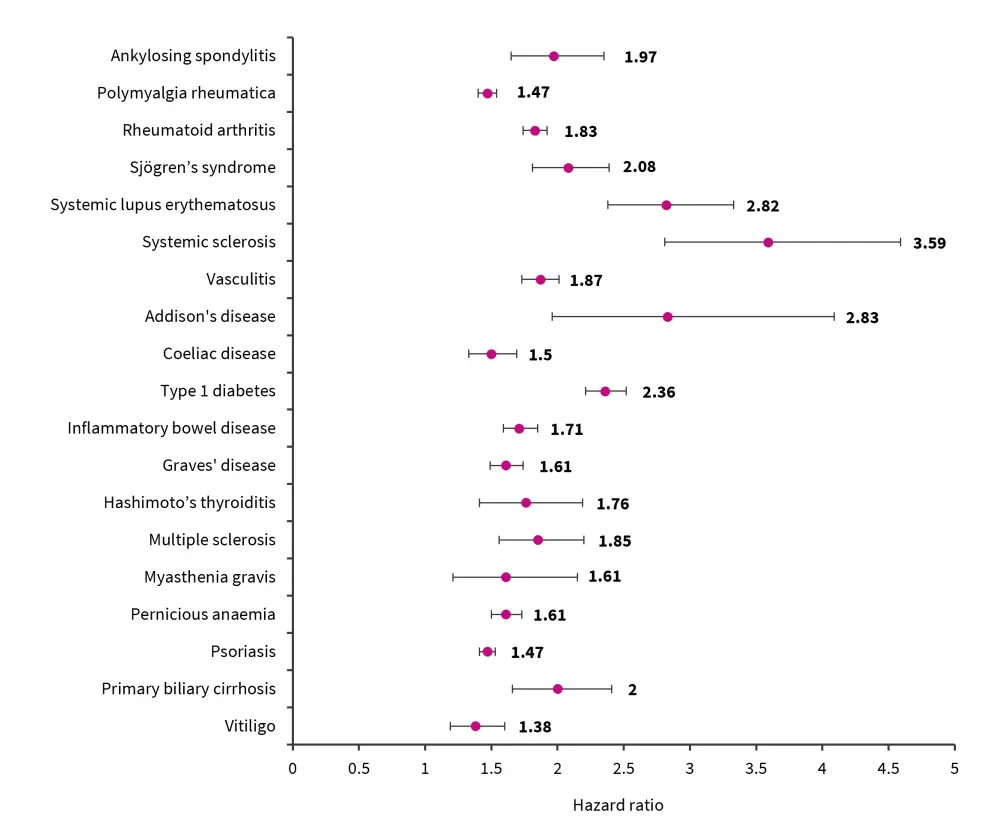

In the analyses, all 19 autoimmune diseases were associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, although the increased risk between patients with autoimmune disease and the matched controls varied for each disease (hazard ratios [HR] are shown in Figure 1). The autoimmune diseases associated with the highest risk for cardiovascular disease were systemic sclerosis, Addison’s disease, SLE, and type 1 diabetes. A total of 15.3% of patients with autoimmune disease, and 11.0% without, developed incident cardiovascular disease over a median of 6.2 years. The incidence rate of cardiovascular disease was 23.3 events and 15.0 events per 1,000 patient-years in the autoimmune cohort and matched control cohort, respectively (HR, 1.56; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.52–1.59).

Figure 1. Hazard ratios per autoimmune disease*

*Data from Conrad, et al.1

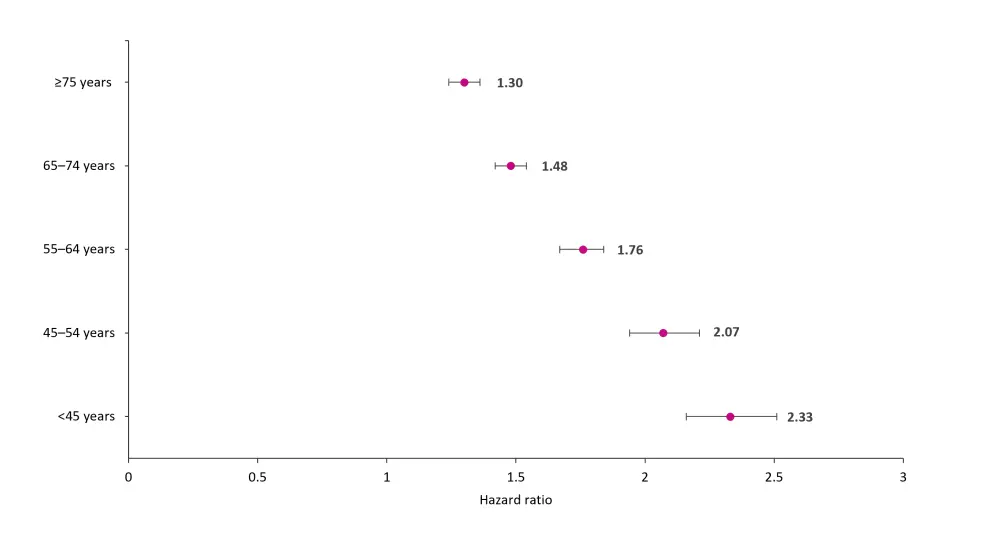

Among the subgroups analyzed (sex, age, socioeconomic status, and calendar year), the highest risk associated with autoimmune disease was age; younger individuals had a higher risk compared with older individuals (unadjusted HRs are shown in Figure 2).

Figure 2. Hazard ratios per age group*

*Adapted from Conrad, et al.1

Cardiovascular disease in the autoimmune disease cohort occurred at a significantly younger age than in individuals in the control cohort (mean age, 67.7 years [standard deviation, 14.1] vs 70.4 years [standard deviation, 13.2]; p < 0.0001). In addition, the risk of cardiovascular disease increased along with the number of autoimmune conditions:

- One autoimmune disease: HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.37–1.45

- Two autoimmune diseases: HR, 2.63; 95% CI, 2.49–2.78

- Three or more autoimmune diseases: HR, 3.79; 95% CI, 3.36–4.27

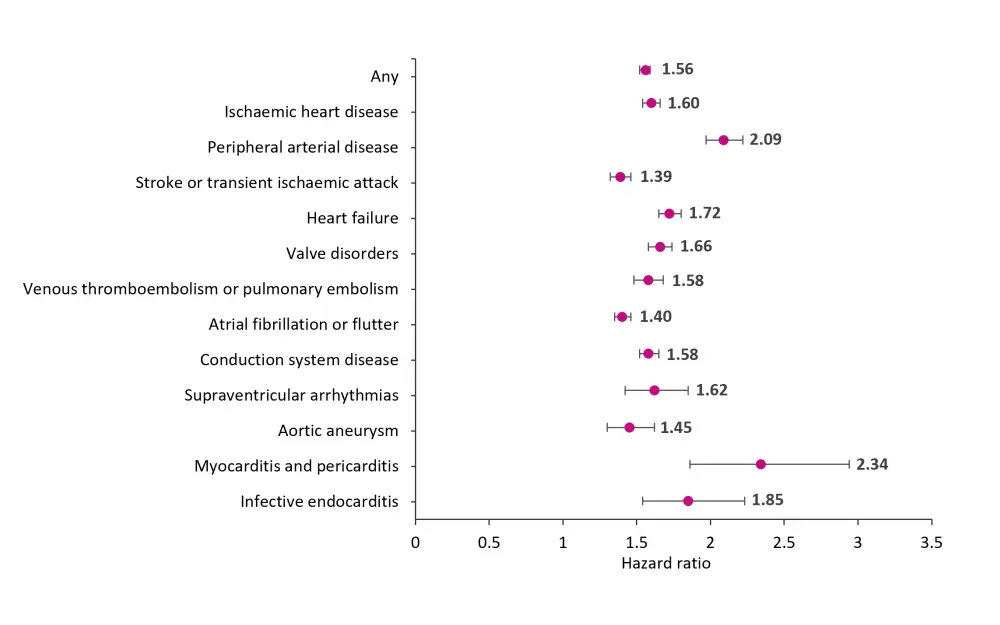

The risk was highest for cardiovascular diseases, such as myocarditis and pericarditis, peripheral artery disease, and infective endocarditis, in patients with autoimmune disease (Figure 3). The authors also observed an increased risk for infection-related heart diseases in patients with autoimmune disease but noted that this may be due to the drugs used in the treatment of autoimmune disease, making patients more susceptible to infections. The excess risk of cardiovascular disease seen in patients with autoimmune disease could not be entirely explained by other classic cardiovascular risk factors, such as age, sex, body mass index, socioeconomic status, cholesterol, smoking, type 2 diabetes, and blood pressure. In addition, analysis further showed that patients with autoimmune disease had a higher risk for mortality associated with cardiovascular disease, when compared with the matched cohort.

Figure 3. Hazard ratios per cardiovascular disease*

*Data from Conrad, et al.1

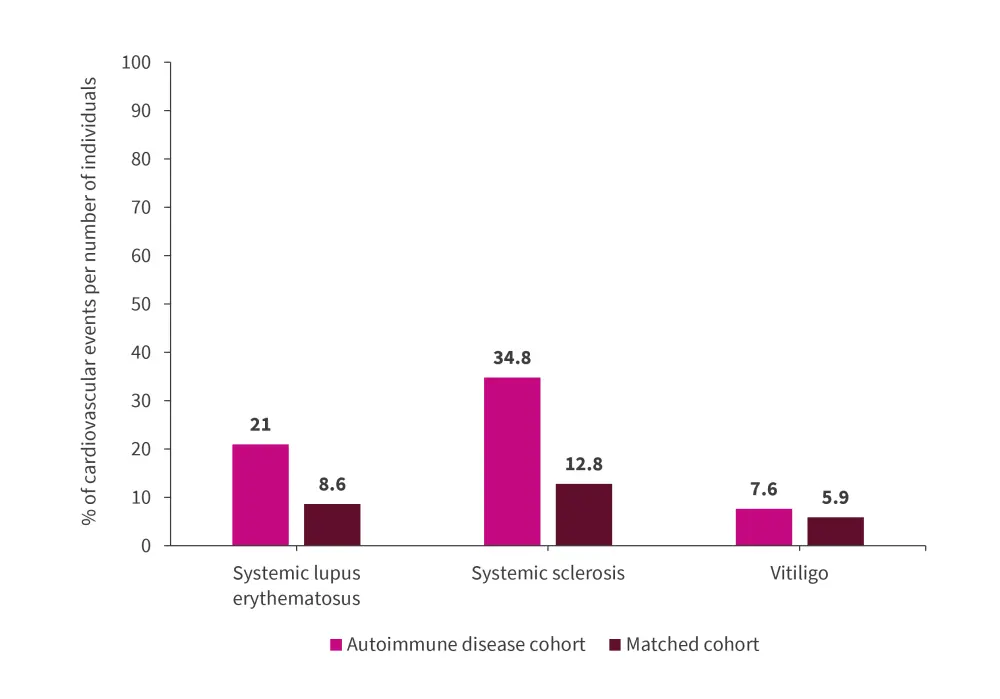

Risk among patients with SLE

In total, there were 2,204 cardiovascular events in patients with SLE. The percentage of cardiovascular events per the number of individuals with SLE compared to the matched cohort is shown in Figure 4, alongside systemic sclerosis, which had the largest difference in cardiovascular events between the cohorts, and vitiligo, which had the least difference.

Figure 4. Percentage of cardiovascular events per number of individuals with systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, or vitiligo*

*Data from Conrad, et al.1

Conclusion

The findings published by Conrad, et al. support previous work demonstrating an increase in cardiovascular risk associated with autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and SLE. All 19 autoimmune diseases studied were associated with an increased cardiovascular risk, which suggests that autoimmunity may actually be the risk factor and that the contribution this makes to cardiovascular disease in these individuals may be greater than previously thought. This was particularly striking in younger individuals, leading to premature cardiovascular disease and associated mortality and disability.

Analysis of risk between autoimmune disease and cardiovascular disease in this study did not consider any drug therapy taken by patients, such as antirheumatics or steroids. In addition, using health record databases relies on the data being accurately inputted at the time; though studies have assessed the validity of diagnoses in the CPRD and reported a positive predictive value of 90% for many conditions. Conrad, et al. highlight that the large cohorts established in this study allowed for stratified analysis and wide representation, highlighting the higher cardiovascular risk in autoimmune diseases with systemic pathology, such as SLE, compared with more localized disease, such as vitiligo.

Although risk of cardiovascular disease was found to be similar in a grouped analysis of connective tissue diseases (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.63–1.74) and organ-specific autoimmune diseases (HR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.56–1.64), autoimmune diseases with autoantibody-mediated pathology, such as SLE, were associated with higher cardiovascular risk. The pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease in SLE is well documented, with autoantibodies, nucleic acids, and complex lipids participating in various pathways which contribute to immune complex-associated endothelial damage, thrombocytopenia, and thrombosis.

The results of this study demonstrate that autoimmune diseases (such as SLE) are an inherent risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease, and as such patients may benefit from strategies to reduce this risk as a part of routine autoimmune disease management.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content