All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The lupus Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lupus Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lupus and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lupus Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported through a founding grant from AstraZeneca. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lupus content recommended for you

HCQ dose and risk of hospitalization in patients with SLE

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is a first-line treatment for patients with systematic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and its use is associated with a reduced risk of lupus flares, improved survival, and decreased cardiovascular and renal events.1

However, long-term use of HCQ is associated with increased risk of retinopathy.1 HCQ dosing has been examined in recent years with a reduction to <5 mg/kg/day recommended in the 2016 American Academy of Ophthalmology Guidelines,2 which would have decreased the dose for many patients who had previously been given 400 mg/day.

During the ACR Convergence 2022, Nestor1 presented data on whether this reduction in HCQ dosing leads to an increase in flares requiring hospitalization in patients with SLE compared with traditional doses.

Study design

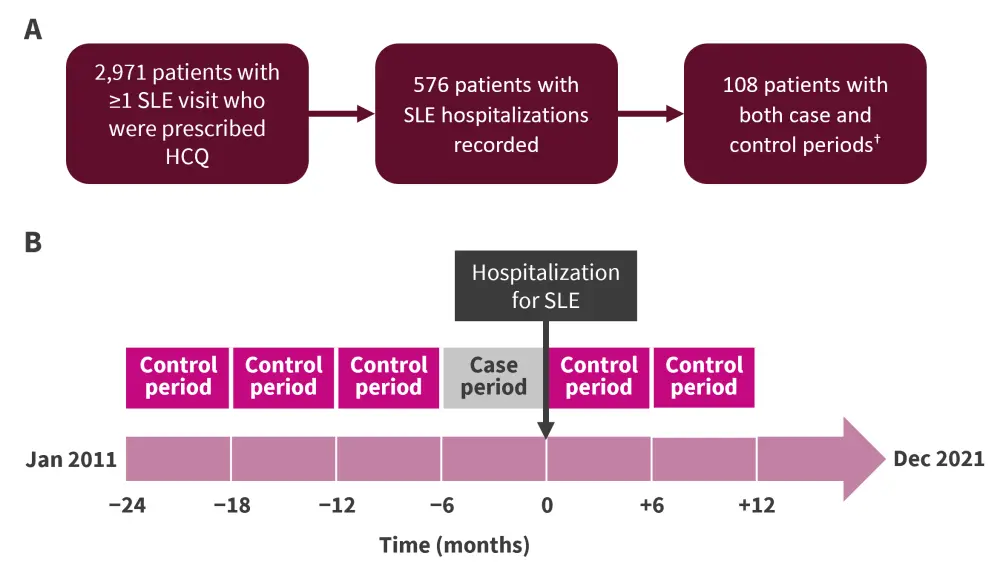

This was a case-crossover study using data from the Massachusetts General Brigham SLE cohort. Patients were selected as indicated in Figure 1.

Both the case and the control periods were 6 months long (Figure 1). The control period was a 6‑month period that did not end in hospitalization for SLE, whereas patients were hospitalized at the end of the 6-month case period. Up to three case periods and three control periods were allowed as part of the study, with preference given to control periods before the case period.

Figure 1. A Patient selection schema and B study design*

HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; SLE, systematic lupus erythematosus.

*Adapted from Nestor.1

†Both the case and control groups received HCQ.

The HCQ exposures examined included weight-based HCQ dosing (either low dose [≤5 mg/kg/day] or high dose [>5 mg/kg/day]) and non-weight-based (low dose [<400 mg/day] or high dose [400 mg/day]).

Results

Baseline characteristics for the whole cohort and the ones included in the case-crossover study are shown in Table 1. While the majority of patients in the total cohort were white (64.3%), in the case-crossover study there was an increase in the proportion of Black patients (32.4% in the case-crossover study vs 16.4% in the overall study) and Hispanic patients (11.1% in the case-crossover study vs 4.4% in the overall study).

Most patients (68.9%) weighed <80 kg in the case-crossover study and therefore should receive <400 mg/day HCQ according to current ophthalmology guidelines.

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics*

|

dsDNA, double stranded DNA; SD, standard deviation; SLE, systematic lupus erythematosus. |

||

|

Baseline characteristic, % (unless otherwise stated) |

Overall |

Case-crossover study |

|---|---|---|

|

Mean age, years (SD) |

44.7 (15.9) |

35.9 (15.2) |

|

Female |

91.0 |

91.7 |

|

Race/ethnicity |

|

|

|

White |

64.3 |

43.5 |

|

Black |

16.4 |

32.4 |

|

Asian |

6.1 |

5.6 |

|

Hispanic |

4.4 |

11.1 |

|

Other/unknown |

12.8 |

16.7 |

|

Mean weight, kg (SD) |

72.4 (19.4) |

72.1 (23.4) |

|

Weight <80 kg |

72.0 |

68.9 |

|

Mean height, cm |

163.3 (8.3) |

161.6 (8.9) |

|

Chronic kidney disease |

3.3 |

1.9 |

|

SLE serologies |

|

|

|

dsDNA antibody |

43.3 |

82.4 |

|

Low complement levels |

46.2 |

82.4 |

|

SLE medications |

|

|

|

Glucocorticoid |

15.5 |

13.9 |

|

SLE immunosuppressant |

8.2 |

9.3 |

The low-dose HCQ doses in both the weight-based and non-weight-based groups were associated with an increased odds ratio for hospitalization for SLE (Table 2).

Table 2. Odds ratio analysis for different dosing groups*

|

CI, confidence interval; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; OR, odds ratio; SLE, systematic lupus erythematosus. |

||||

|

HCQ dose |

Case periods, n |

Control periods, n |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR† (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Weight-based dose |

||||

|

High dose (>5 mg/kg/day) |

33 |

83 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

Low dose (≤5 mg/kg/day) |

84 |

156 |

4.68 (1.66−13.20) |

4.41 (1.50−12.98) |

|

Non-weight-based dose |

||||

|

High dose (400 mg/day) |

55 |

139 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

Low dose (<400 mg/day) |

63 |

101 |

3.78 (1.51−9.51) |

3.48 (1.33−9.13) |

This study had some limitations. Complete adherence to HCQ treatment was not monitored (e.g., dispensing records) and alternative reasons for lower HCQ dosing such a gastrointestinal or renal issues were also not accounted for; however, Nestor commented that chronic kidney disease prevalence was low in the study population.

Conclusion

This case-control study found that lower doses of HCQ were associated with an increased risk of hospitalization in patients with SLE. As a result of these data, the dosing of HCQ may need to be reexamined. Retinopathy is a side effect of long-term HCQ use, and while flares may be short-term, they result in increased organ damage. In addition, treatment of flares with other agents, such as glucocorticoids, can result in increased side effects. The speaker suggested that in order to overcome the risk of lupus flare resulting in hospitalization, increased HCQ dosing could be utilized earlier in the disease course or in those patients with more active disease.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content