All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The lupus Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lupus Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lupus and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lupus Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported through a founding grant from AstraZeneca. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lupus content recommended for you

Immunosuppressive treatment patterns in patients with LN: A real-world study from the United States

Do you know... What percentage of patients with LN do not respond to existing treatments?

Lupus nephritis (LN) represents a serious complication associated with approximately 40% of people living with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Moreover, around 30% of people with LN do not respond to current treatment approaches.

As per the 2012 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines, patients with LN are recommended to undergo 6 months of induction therapy with immunosuppressants, such as cyclophosphamide (CYC) or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), alongside corticosteroids. It is then recommended that patients who respond undergo maintenance therapy with either MMF alone, or azathioprine (AZA) with or without corticosteroids. Patients who do not respond to induction treatment are recommended to switch from MMF to CYC and vice versa, with concomitant corticosteroids. Rituximab is also recommended for patients in whom induction therapy fails to yield a response, or who worsen during induction, with either MMF, CYC, or both. Calcineurin inhibitor use, or belimumab, may also be considered, although this doesn’t feature in the ACR guidelines.

However, there is a limited availability of real-world data concerning patients switching to alternate induction immunosuppressants, the proportion of patients successfully transitioning from induction to maintenance immunosuppressants or re-initiating induction immunosuppressants, and corticosteroids burden in this population.

To address the unmet need within the current treatment paradigm, Hunnicutt et al.1 published an article in Rheumatology and Therapy characterizing immunosuppressant treatment patterns among patients with LN in United States (US) routine care settings. Here, we are pleased to summarize the key findings.

Methods

This real-world, retrospective cohort study used US insurance claims data collected between 2012 and 2019. Patients diagnosed with LN in the 12 months preceding index data, prescribed with an immunosuppressant of interest (CYC, MMF, or AZA), and with 12 months of medical and drug coverage preceding the index date were included. Patients were categorized into induction and maintenance immunosuppressant cohorts based on the treatment they were receiving. The induction cohort included patients initiating CYC with MMF, but also receiving pulse corticosteroids. The maintenance cohort included patients initiating MMF without pulse corticosteroids, or AZA with or without corticosteroids.

The outcomes assessed were:

- time to switching between or re-initiating induction immunosuppressants;

- time to conversion to maintenance immunosuppressants; and

- corticosteroid treatment patterns.

Results

In total, 5,000 patients with LN were included, contributing to 5,516 treatment episodes. The baseline patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Around 80% of patients in both cohorts were female, with a mean age of 38.5 years (standard deviation [SD], 13.2) and 41.6 (SD, 12.6) years in the induction and maintenance cohorts, respectively. In the year preceding the index date, SLE-related conditions and healthcare utilizations were higher in the induction cohort compared with the maintenance cohort.

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics*

|

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin-II receptor blocker; AZA, azathioprine; CYC, cyclophosphamide; ED, emergency department; IV, intravenous; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; SD, standard deviation; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus. |

||||

|

Characteristic, % (unless otherwise stated) |

Induction immunosuppressant cohort |

Maintenance immunosuppressant cohort |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

MMF with pulse corticosteroids (n = 182) |

CYC with pulse corticosteroids (n = 190) |

MMF (n = 3,902) |

AZA (n = 1,242) |

|

|

Mean age (SD), years† |

37.6 (12.7) |

39.3 (13.6) |

41.5 (12.7) |

42.0 (12.4) |

|

Female† |

84.6 |

79.5 |

83.9 |

88.8 |

|

SLE-related conditions of interest‡ |

||||

|

Arthritis/arthralgia |

55.0 |

51.1 |

43.6 |

51.5 |

|

Myalgia/myositis |

18.1 |

12.6 |

10.4 |

14.5 |

|

Pleurisy/pleural effusion |

14.8 |

22.6 |

13.0 |

13.3 |

|

Rash |

34.6 |

37.9 |

31.2 |

34.3 |

|

Prior SLE-related medications of interest‡ |

||||

|

ACE inhibitors/ ARBs |

50.0 |

60.5 |

60.5 |

53.5 |

|

Antimalarials |

58.2 |

61.6 |

56.5 |

65.8 |

|

AZA |

6.0 |

12.1 |

10.2 |

36.2 |

|

Belimumab |

16.5 |

7.9 |

3.9 |

5.5 |

|

Cyclosporine |

1.1 |

2.1 |

2.5 |

1.7 |

|

IV CYC |

8.8 |

12.6 |

5.2 |

6.9 |

|

MMF |

32.4 |

48.4 |

46.2 |

27.8 |

|

Oral corticosteroids |

83.5 |

89.0 |

76.5 |

80.6 |

|

Rituximab |

14.3 |

9.0 |

2.2 |

4.0 |

|

Tacrolimus |

3.9 |

6.3 |

7.5 |

5.2 |

|

Healthcare utilization‡ |

||||

|

Any dialysis event |

7.7 |

12.6 |

11.4 |

9.5 |

|

Any hospitalization |

43.4 |

61.1 |

38.8 |

37.9 |

|

Any ED visit |

55.0 |

59.5 |

45.8 |

50.2 |

|

≥1 rheumatologist visit |

64.3 |

64.7 |

61.9 |

68.9 |

|

≥1 nephrologist visit |

64.3 |

69.5 |

65.7 |

56.7 |

Switching between or re-initiating induction immunosuppressant therapy

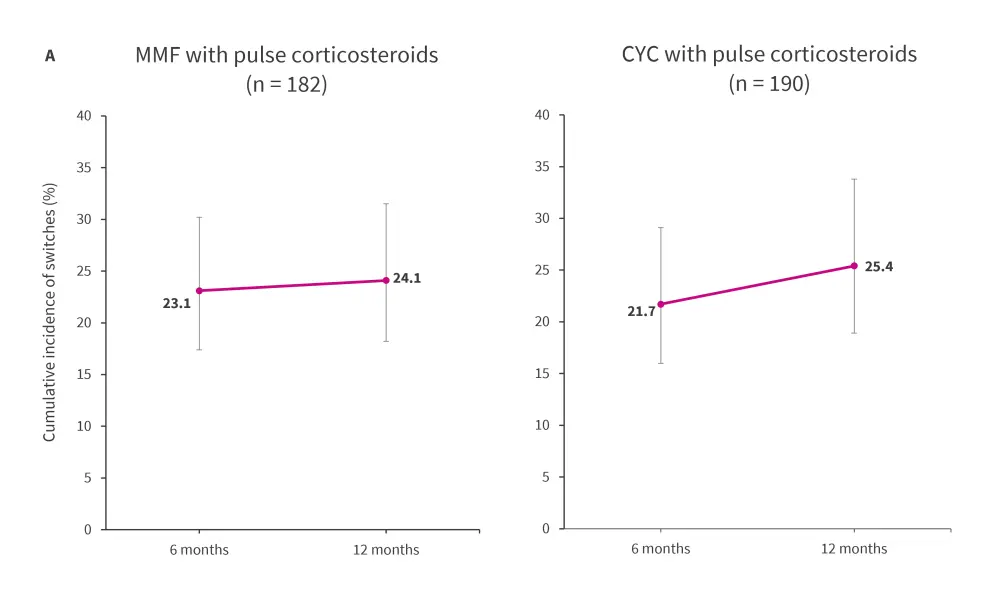

The induction immunosuppressant cohort comprised 372 treatment episodes, with 80 instances of transitioning to an alternative induction immunosuppressant observed within 12 months of treatment initiation, over a follow-up of 178 person-years. The cumulative incidence of treatment switches with MMF and CYC at 6 and 12 months of treatment initiation are presented in Figure 1A.

Over a follow-up period of 4,291.7 person-years, 1,023 re-initiations of induction immunosuppressant therapy within 48 months of treatment initiation were identified (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Incidence of transitioning between or re-initiating induction immunosuppressive treatment in the A induction and B maintenance cohorts*

AZA, azathioprine; CYC, cyclophosphamide; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; n, treatment episodes.

*Data from Hunnicutt, et al.1

The error bars represent 95% confidence interval

Conversion to maintenance immunosuppressive therapy

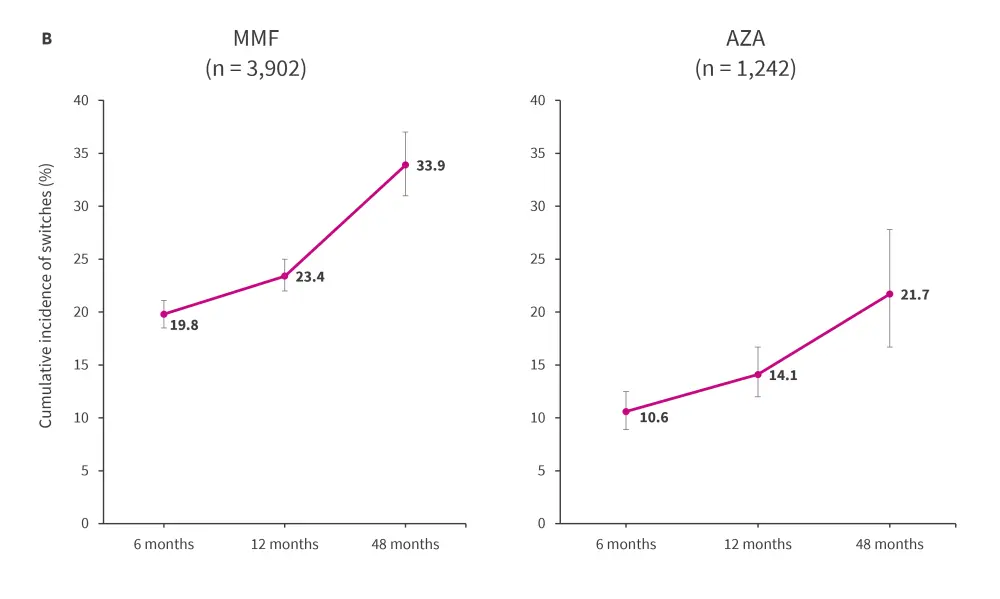

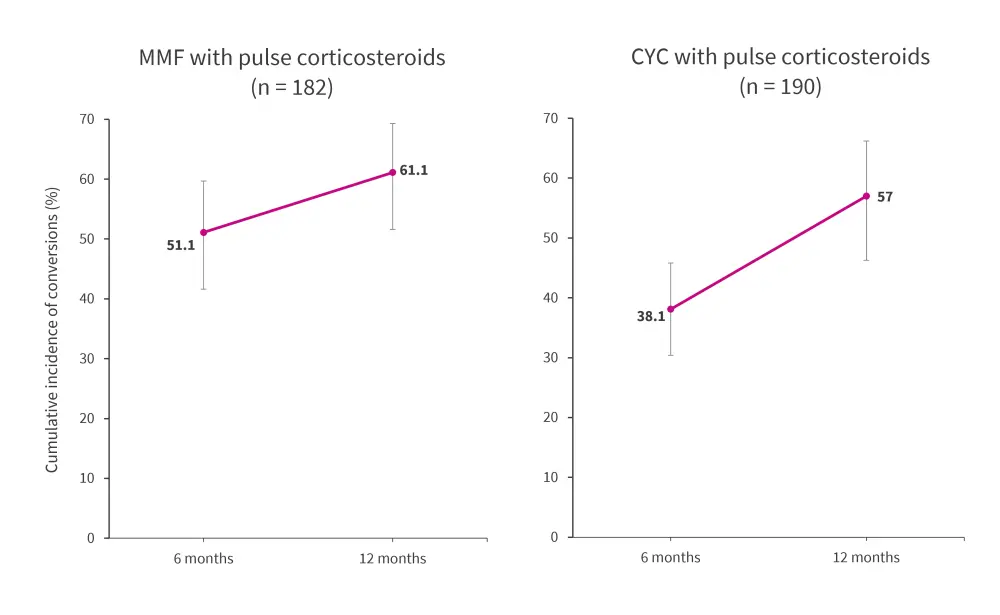

Within a year of treatment initiation, 138 conversions to maintenance immunosuppressants were observed during 144.2 person-years of follow-up (Figure 2). At 12 months, the cumulative incidence of conversion to maintenance immunosuppressive therapy was 59.6% (95% confidence interval [CI], 52.4–66.1) among the total cohort. Irrespective of whether patients received MMF or CYC induction therapy, a greater proportion of patients switched to maintenance with MMF than AZA.

Figure 2. Incidence of converting to maintenance immunosuppressives within the induction cohort*

CYC, cyclophosphamide; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil.

*Data from Hunnicutt, et al.1

Corticosteroids burden

Despite an overall decrease in use of oral corticosteroids among patients in the induction cohort during follow-up, 50.8% of patients continued to use oral corticosteroids at any dosage and 21.5% remained on high (≥7.5 mg/day) prednisone equivalent doses at 12 months.

The pattern of oral corticosteroids use was similar between CYC and MMF, whereas the use of pulse corticosteroids seemed to be lower with MMF versus CYC during follow-up.

Patients in the maintenance immunosuppressant cohort reported gradual decrease in use of oral corticosteroids at any dose from 61.4% to 44.1% at 24 months of follow-up. While the use of daily high prednisone equivalent doses also decreased, 15.8% of them continued to be on high doses at 24 months.

Conclusion

This real-world study found that a quarter of the patients with LN initiating immunosuppressants switched to an alternate treatment, while at least a fifth in the maintenance immunosuppressant cohort recommenced induction therapy at 12 months. This suggests that a substantial number of patients do not exhibit an adequate response to existing therapies for LN. Furthermore, despite an initial decline in oral corticosteroid use, half of the patients were still using them at 12 months of follow-up, indicating the corticosteroid burden in these patients.

The study had several limitations, including limited clinical information, the potential for disease misclassification within claims databases, with the use of prescription claims as a proxy measure instead of actual use, a relatively smaller number of patients in the induction cohort compared with the maintenance cohort, and the likelihood that patients within claims databases may have a higher prevalence of chronic conditions, which could limit the generalizability of the study findings to the broader US population.

The study highlights the unmet needs within the current treatment strategies for LN, and emphasizes the need for more efficacious, well-tolerated, and corticosteroid-sparing treatments alternatives.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content