All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The lupus Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lupus Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lupus and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lupus Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported through a founding grant from AstraZeneca. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lupus content recommended for you

Management of lupus nephritis

Do you know... Managing lupus nephritis (LN) can be challenging, especially in populations with specific requirements. Which agent is recommended as part of the induction treatment regimen for pregnant patients with class III/IV LN?

The management of lupus nephritis (LN) has benefitted from the recent release of two guidelines, one from the European League for Rheumatism (EULAR) jointly with the European Renal Association (ERA) in 20191 and the other from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) in 20212.

While these guidelines are largely compatible, there had been updates in scientific evidence between the publication of the EULAR recommendations and the KDIGO guidelines. In their article published in Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation late in 2021, Anders et al.3, of ERA, sought to identify and clarify the differences between the two guidelines. We will summarize this publication, along with more recent updates that have taken place since it was published, in this summary article.

Treatment of LN3

Hydroxychloroquine

There are differences in how the starting dose of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is calculated between the KDIGO guidelines and EULAR recommendations, but for most adults it will not exceed 400 mg. Anders, et al. highlight some slight differences between the guidelines in screening for ocular complications. Most patients with LN will begin HCQ therapy at an early stage of chronic kidney disease, and therefore, annual ocular checks after 5 years of treatment are likely to be safe. However, they recommend that in patients with more advanced chronic kidney disease, annual ocular screening should be performed from treatment outset. Rarely, cases of HCQ toxicity as a persistent cause of proteinuria in LN may occur with Fabry-like zebra bodies being visible.

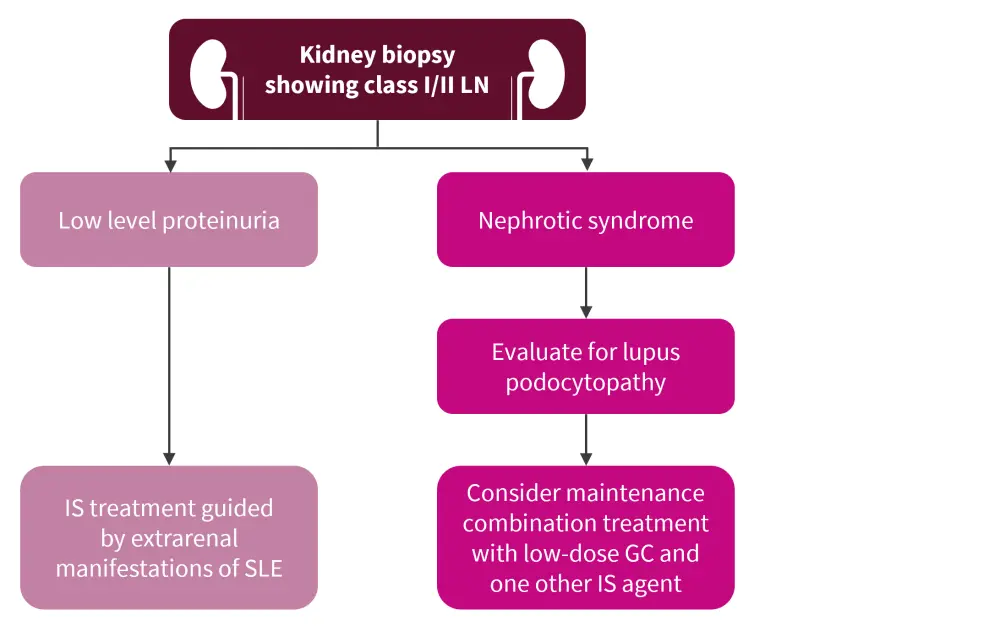

Class I/II LN management

The EULAR 2019 recommendations differ slightly from those shown in Figure 1 (adapted from the KDIGO 2021 guidelines2) in that no specific recommendations for immunosuppressive treatments are made aside from the therapy selected to manage general non-renal systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) symptoms. Repeat biopsies are advised in the EULAR recommendations if there is significant proteinuria to detect class changes.

Figure 1 also describes treatment for lupus podocytopathy, which is not included in the EULAR recommendations, but is a condition that may benefit from a specific diagnostic work-up and management strategy.

Figure 1. Management of class I/II LN*

GC, glucocorticoids; IS, immunosuppressive; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

*Adapted from KDIGO Glomerular Diseases Work Group.2

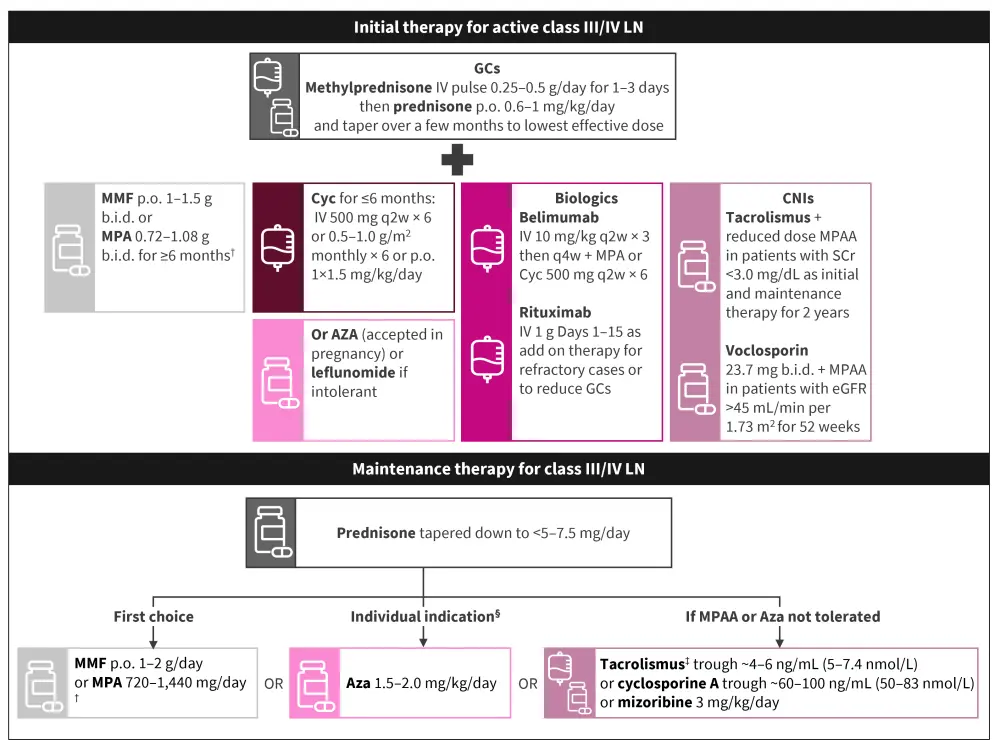

Class III/IV LN induction therapy3

Both guidelines recommend initial intravenous glucocorticoid (GC) treatment to reduce tissue inflammation in the kidney rapidly, followed by an oral GC regimen. Recent trial data have highlighted a trend towards a lower starting oral GC dose with a more rapid taper, suggesting this may be as effective as traditional dosing regimens. Figure 2 details the induction regimen recommended by the KDIGO guidelines, describing oral prednisolone at 0.6–1 mg/kg (max. 80 mg) and tapering to <5–7.5 mg/day over a few months, which is in contrast to the EULAR recommendations that suggest oral prednisone at 0.3–0.5 mg/kg/day for up to 4 weeks, tapered to ≤7.5 mg/day by 3–6 months.

With respect to treatment with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF)/mycophenolate acid (MPA), both guidelines make similar recommendations (Figure 2). However, the KDIGO guidelines recommend the preferential use of cyclophosphamide (Cyc) if suboptimal adherence is expected. In addition, the KDIGO guidelines make recommendations for specific populations; for patients at risk of infertility, of Asian, Hispanic, or African American ancestry, or who have had moderate to high Cyc exposure, MMF/MPA is preferred.

Alternative agents are covered in more detail by the KDIGO guidelines and include belimumab, following the recent U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)4 and European Medicines Agency (EMA)5 approvals, for the treatment of active LN, rituximab for repeated flares, and azathioprine (Aza) for pregnant patients. Belimumab is discussed further in the recent trial updates section below.

If patients cannot tolerate Cyc or MMF/MPA, calcineurin inhibitors may be considered following data from trials in Asia.

Class III/IV LN maintenance therapy3

While MPA/MMF are considered of equal efficacy to Aza by EULAR, KDIGO prefers the former following the results of the MAINTAIN study. However, the extended ALMS trial (NCT00377637) found Aza to be inferior to MMF and resulted in more frequent cytopenias. In addition, Aza is more compatible for patients contemplating pregnancy so may be recommended in specific circumstances (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Treatment for class III/IV LN*

Aza, azathioprine; b.i.d., twice daily; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; Cyc, cyclophosphamide; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GC, glucocorticoid; IV, intravenous; LN, lupus nephritis; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MPA, mycophenolate acid; p.o., oral; q2wk, every 2 weeks; q4wk, every 4 weeks; SCr, serum creatinine.

*Adapted from KDIGO Glomerular Diseases Work Group.2

†Preferred over cyclophosphamide if patient is of Asian, Hispanic, or African American ancestry.

‡Data mostly from Chinese patients.

§In patients contemplating pregnancy, or if MMF/MPA is unavailable, they are intolerant, or it is too costly.

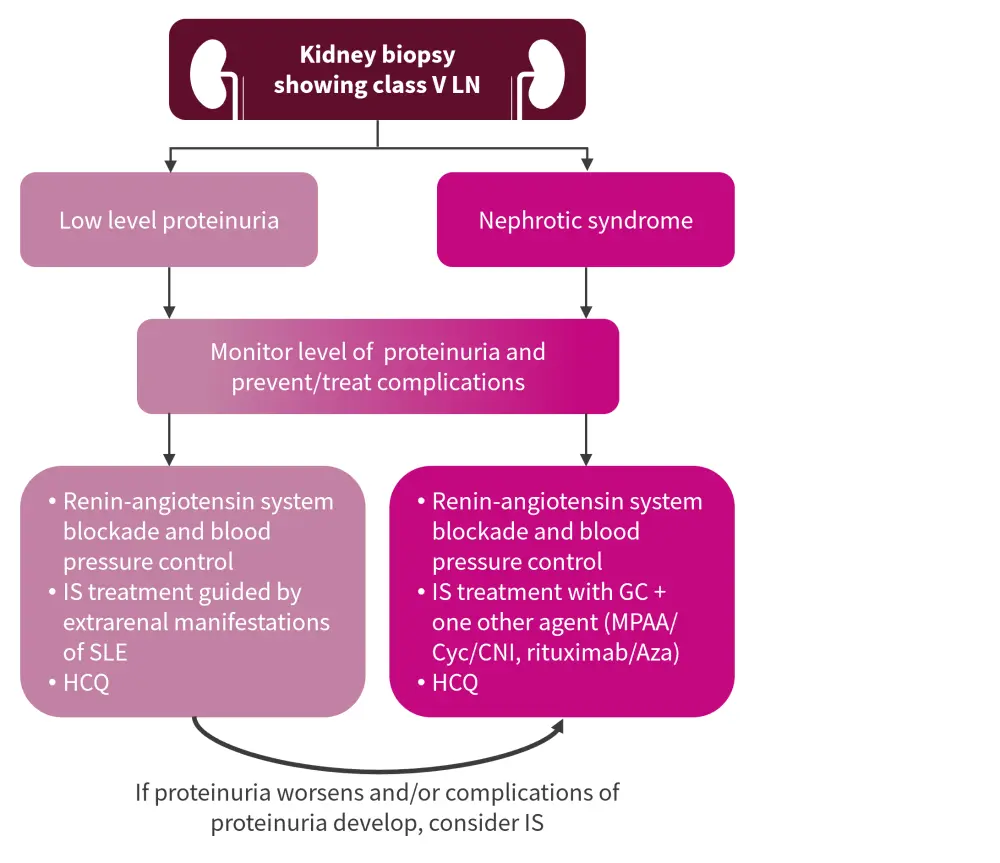

Class V LN management

The EULAR recommendations suggest the use of Cyc and tacrolimus, each in combination with GCs, in addition to the agents recommended by KDIGO, shown in Figure 3. However, this recommendation is based on data from Chinese patients only, and Anders et al.3 caution against extrapolating this to European patients, highlighting that more data are needed to support this recommendation.

Figure 3. Class V LN management*

Aza, azathioprine; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; Cyc, cyclophosphamide; GC, glucocorticoids; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; IS, immunosuppressive; LN, lupus nephritis; MPAA, mycophenolate acid analogs; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

*Adapted from KDIGO Glomerular Diseases Work Group.2

Failure of treatment

Both guidelines refer to a treatment target of proteinuria reduction to <0.5-0.7 g/24 hours at 12 months with glomerular filtration rate normalization/stabilization, but failure to achieve this is common in patients with LN. Both guidelines highlight the importance of assessing whether the lack of response is due to a patient being refractory to the treatment or lack of adherence. For patients with persistently active LN despite adequate dosing, both guidelines suggest a list of therapies, including rituximab, belimumab, and obinutuzumab. The EULAR recommendation also refer to the use of intravenous immunoglobulins and plasma exchange in these patients, though the evidence is from single-center uncontrolled studies of patients with SLE with/without LN.

Relapse therapy

The EULAR recommendations do not mention this area, but the KDIGO guidelines recommend the same use of therapy as in the first episode, but highlight the cumulative Cyc exposure risk, which may necessitate altering the first-line agent used.

Pregnancy

The majority of patients with LN are women of child-bearing age, therefore guidance for fertility and pregnancy-related issues is important. Pregnancy outcomes can be poor both in patients with active LN and untreated disease. The two guidelines agree on which drugs to avoid and which are recommended if a patient is or is considering becoming pregnant. Neither the KDIGO guidelines or the EULAR recommendations detail risks factors for pre-eclampsia, such as obesity, chronic kidney disease stage, and proteinuria level, or discuss the impact of anti-Ro and anti-phospholipid antibodies.

Pediatrics

Both guidelines state that pediatric patients with LN should be treated in a similar fashion to adult patients, though the KDIGO guidelines do note that issues, such as dose adjustment, growth, fertilty and psychological issues, need to be considered with this population.

Recent trial updates6

Belimumab

While belimumab is already included in the KDIGO guidelines, recent trials have provided interesting data. The efficacy of belimumab was recently tested in the BLISS-LN phase III trial (NCT01639339). The primary endpoint was renal response; 43% of patients treated with belimumab and current standard of care (SoC) achieved this compared with 32% in the placebo + SoC arm (odds ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.0–2.3; p = 0.03). The risk of renal-related events (a composite endpoint of end-stage kidney disease, doubling of serum creatinine, increased proteinuria or impaired kidney function or kidney disease-related treatment failure) or death, was less in patients treated with belimumab, and both treatment groups had similar safety profiles.

Post hoc analysis also investigated belimumab’s efficacy in patients who remained on the study after 24 weeks when MMF and glucocorticoids were tapered. These patients treated with belimumab demonstrated a reduced risk of renal relapse (hazard ratio, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.28–0.72) and a lower rate of estimated GFR (eGFR) decline (eGFR slope difference, 3.61; 95% CI, 0.15–7.06) compared with the placebo group.

Voclosporin

Voclosporin was examined in two randomized control trials in multiethnic patients following positive data on the role of calcineurin inhibitors for patients with LN in Asian populations. The phase II AURA-LV (NCT02141672) and phase III AURORA (NCT03021499) trials assessed the safety and efficacy of voclosporin in larger cohorts of patients with LN. In the AURORA trial, voclosporin produced a complete renal response rate (CRRR) at 52 weeks of 41% vs 23% in the placebo group (odds ratio, 2.65; 95% CI, 1.64–4.27). Voclosporin was approved by the U.S. FDA in January 2021 in combination with MMF for the treatment of patients with LN.7

Obinutuzumab

Obinutuzumab is a humanized type II anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody that has been investigated in the NOBILITY phase II trial (NCT02550652) in patients with LN. Obintuzumab achieved a CRRR of 35% vs 23% with placebo at 52 weeks and 41% vs 23% at 104 weeks, without any significant safety concerns.

Anifrolumab

Anifrolumab has been tested in patients with general SLE in the TULIP trials but patients with LN were excluded from these. To test anifrolumab in patients with LN, a separate phase II TULIP-LN trial (NCT02547922) was performed. However, anifrolumab did not meet its primary endpoint at 52 weeks (relative difference in 24-hour urine protein−creatinine ratio) when the combined anifrolumab treatment groups were compared with the placebo group. When comparing just the intensified anifrolumab regimen treatment group with the placebo group, anifrolumab outperformed placebo, with a CRRR of 45.5% vs 31.1%, respectively (p = 0.162), and herpes zoster infection was higher in the treatment group.

Conclusion

Having two recently published guidelines for clinicians treating patients with LN is hugely beneficial for the field. The two guidelines provide mostly consistent recommendations, with the few differences being highlighted in this article. Some of the differences between the KDIGO guidelines and EULAR recommendation may be due to the different geographical scope of the panels (with KDIGO having a more international outlook), the split of expertise areas of the healthcare professionals on the panels, or the lack of evidence in particular areas. With the advent of new agents being introduced to the field, updates to both guidelines may be forthcoming and could see the addition of belimumab and voclosporin for younger patients, those with relapsing disease or proteinuria, or for patients with disease-related or GC damage.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content