All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The lupus Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lupus Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lupus and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lupus Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported through a founding grant from AstraZeneca. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lupus content recommended for you

Network meta-analysis comparing the efficacy and safety of maintenance therapies for LN

Renal impairment is observed in up to 60% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and lupus nephritis (LN) remains the biggest cause of morbidity and mortality in these patients. The therapeutic management of LN involves an induction phase, which aims to induce disease remission. This is then followed by a maintenance phase, intended to prevent recurrence and progression to end-stage renal disease.

Among the immunosuppressive agents used to treat LN, cyclophosphamide (CYC) has long been considered the gold standard for inducing remission and preventing renal flares. However, its use requires careful consideration due to significant drug-related adverse effects, which include susceptibility to severe infections, bone marrow suppression, malignancy, and ovarian toxicity. Other immunosuppressive drugs used to treat LN include mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), azathioprine (AZA), and calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) such as cyclosporin and tacrolimus.

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated significant efficacy and safety of CNI, MMF, and AZA as maintenance therapies in patients with LN. However, there is a lack of head-to-head comparison data. Only a small number of RCTs have investigated the relative efficacy of these maintenance therapies, but the findings were ambiguous due to small patient populations.

To address this, Lee et al.1 performed a network meta-analysis (NMA) evaluating the relative efficacy and safety of CNI, MMF, and AZA as maintenance therapies in patients with LN. Below, we summarize the key findings from their article recently published in Zeitschrift für Rheumatologie.

Methods

A literature search was carried out using the keywords “lupus nephritis,” “maintenance treatment,” “tacrolimus,” “cyclosporine,” “mycophenolate mofetil,” and “azathioprine” in PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register to identify relevant articles until December 2022.

RCTs were screened based on the following inclusion criteria:

- assessed CNI or MMF versus AZA, or CNI versus MMF as maintenance therapy for LN;

- provided efficacy and safety outcomes of CNI, MMF, and AZA; and

- enrolled patients with biopsy-proven LN class III, IV, or V.

The efficacy outcome was LN relapse. The safety outcomes were; number of patient withdrawals due to adverse events (AEs), incidence of infection and leukopenia, and doubling of serum creatinine.

Bayesian NMA was conducted with a random effects model used as a conservative method. Relative effects were converted to probabilities that a certain treatment was best, second best etc. The ranking of the treatments was based on the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) and was expressed as a percentage, with 100% indicating that the treatment is the best, and 0% denoting the worst. A sensitivity analysis was conducted by comparing the random effects model with fixed-effects models.

Results

Overall, 967 studies were identified, of which 16 were selected for full-text review. A total of 10 RCTs (N = 884) met the inclusion criteria for meta-analysis. The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis*

|

AZA, azathioprine; CsA, cyclosporine; CYC, cyclophosphamide; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; NA, not available; TAC, tacrolimus. |

|||||||

|

Study |

Region/ country |

Sample size |

Induction treatment |

Drug dosage of maintenance treatment (n) |

Follow-up period, months† |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TAC/CsA |

MMF |

AZA |

|||||

|

1 |

China |

123 |

MMF, TAC, CYC |

Trough level |

1.0–1.5 g/day |

2 mg/kg |

96 |

|

2 |

Sudan |

81 |

CYC |

NA |

22 mg/kg/day (n = 41) |

2 mg/kg/day |

36 |

|

3 |

China |

70 |

TAC, CYC |

Trough level 4–6 ng/mL |

NA |

2 mg/kg/day (n = 36) |

6 |

|

4 |

International |

227 |

MMF, CYC |

NA |

2 g/day |

2 mg/kg/day |

36 |

|

5 |

European |

105 |

CYC |

NA |

2 g/day |

2 mg/kg/day (n = 52) |

48 |

|

6 |

European |

69 |

CYC |

Trough level 200 ng/mL |

NA |

2 mg/kg/day |

14 |

|

7 |

Hong Kong |

62 |

MMF, CYC |

NA |

1 g/day |

1.5–2 mg/kg/day |

63 |

|

8 |

North America |

59 |

CYC |

NA |

0.5–3 g/day |

1–3 mg/kg/day |

25–30 |

|

9 |

China |

46 |

MMF, CYC |

NA |

1 g/day |

1.5 mg/kg/day |

12 |

|

10 |

Hong Kong |

42 |

MMF, CYC |

NA |

1 g/day |

1.5 mg/kg/day |

12 |

Efficacy

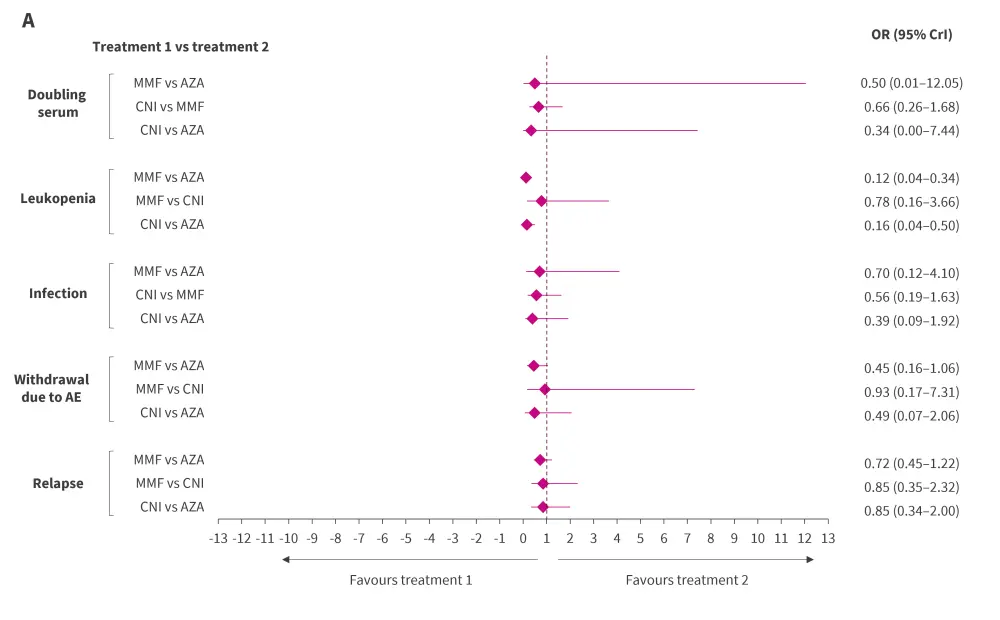

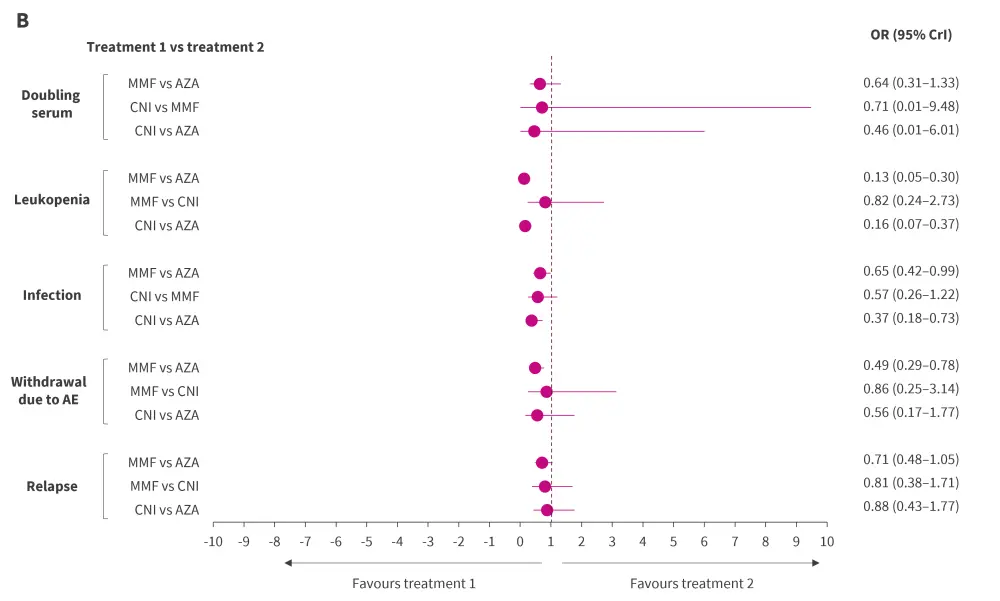

Although not statistically significant, MMF displayed a trend toward a lower relapse rate compared with AZA and CNI (Figure 1). The differences were similar between MMF vs CNI and CNI vs AZA.

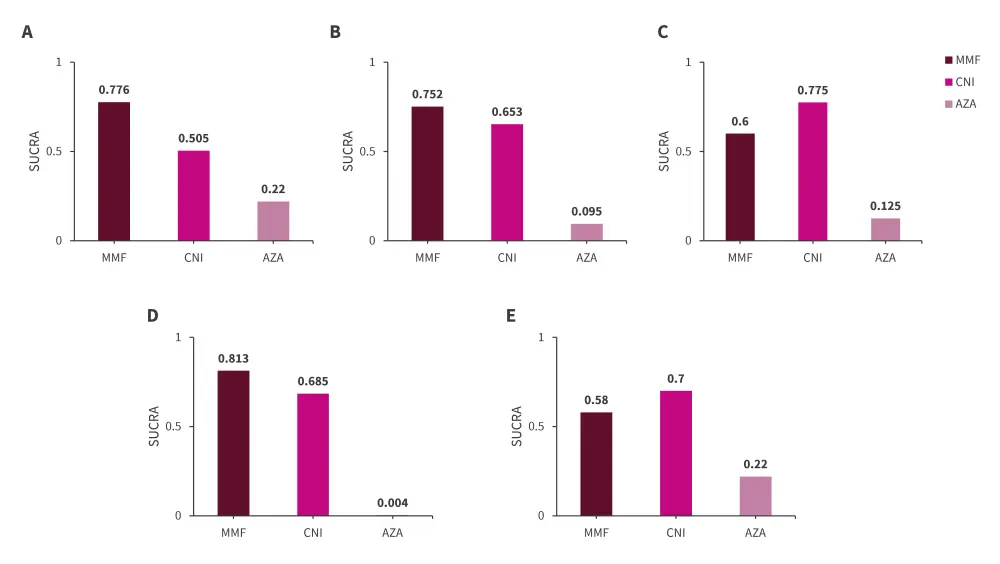

The SUCRA-based ranking probability indicated that MMF exhibited the highest probability of being the best treatment in terms of renal relapse rate, followed by CNI and AZA (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Bayesian NMA results of relative efficacy and safety of CNI, MMF, and AZA using A random and B fixed effects model*†

AE, adverse event; AZA, azathioprine; CrI, credible interval; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; NMA, network meta-analysis; OR, odds ratio.

*Pooled results were considered statistically significant if 95% CrI did not contain a value of 1.

†Adapted from Lee, et al.1

Figure 2. Ranking probability of CNI, MMF, and AZA based on SUCRA accessing A renal relapse, B withdrawal due to AEs, C number of infections, D leukopenia, and E doubling serum creatine*

AE, adverse events; AZA azathioprine; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; SUCRA, surface under the cumulative ranking curve.

*Adapted from Lee, et al.1

Safety

The number of patient withdrawals due to AEs, incidence of infection, and doubling of serum creatinine levels tended to be lower in the CNI and MMF groups compared with AZA group, although this difference was not statistically significant. However, the incidences of leukopenia were significantly lower with MMF and CNI than AZA.

As per ranking probabilities based on SUCRA, MMF appeared to be the best treatment in terms of number of patient withdrawals and incidence of leukopenia, followed by CNI and AZA. However, when considering incidence of infection and doubling serum creatinine CNI had the highest probability of being the best treatment option, followed by MMF and AZA (Figure 2).

Inconsistency and sensitivity analysis

Inconsistency plots between direct and indirect estimates depicted a low likelihood of network inconsistencies significantly affecting the NMA results. Furthermore, the outcomes from both the random effects (Figure 1A) and fixed effects (Figure 1B) models displayed a consistent pattern for the odds ratios, affirming the robustness of the results obtained.

Conclusion

The NMA findings revealed that MMF was the most effective at preventing relapse in people with LN; however, there were no significant differences. CNI was then the next best treatment in terms of relapse outcomes and had lower infection and doubling serum creatinine risk. Both MMF and CNI had more favorable safety profiles than AZA.

The limitations of this NMA including a limited sample size for tacrolimus, diversity in the study design and patient characteristics, not covering all the elements of drug efficacy and safety, and varying definitions of renal relapse, induction therapy employed, severity of the illness, drug dosage, and duration of follow-up used across the studies. Further studies are warranted to comprehensively evaluate the relative efficacy and safety of CNI, MMF, and AZA in a broader sample size to identify the best maintenance treatment for LN.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content