All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The lupus Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lupus Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lupus and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lupus Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported through a founding grant from AstraZeneca. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lupus content recommended for you

Racial differences in CVD risk in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus

Do you know... A recent study by study Garg, et al., assessed the timing and predictors of incident cardiovascular disease in a predominantly Black population-based systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) cohort. At the 4-year follow-up, how many times higher was the annual stroke rate in Black women aged <55 years, compared with a healthy Black population?

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) represents a 3–5 fold higher mortality rate and accelerated risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in Black people and in particular young Black women compared with the general population.1

In general, Black people with SLE have a three times higher risk of developing end stage renal disease compared with White people with SLE. Moreover, it has also been noted that SLE is diagnosed at a three-fold higher rate in young Black women, who in turn have a three times higher risk of early death.1

As previous studies predominantly involved white patient cohorts, Shivani Garg, et al.,1 conducted a study to assess timing and predictors of incident CVD events in a population-based cohort of predominantly Black patients. The results were recently published in Journal of Rheumatology and we summarize the findings below.

Methods

Patients with SLE identified between 2002 and 2004 were defined by either the 1997 update of the 1982 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) revised classification criteria for SLE or meeting three ACR criteria with a confirmed SLE diagnosis by a board-certified rheumatologist. The USA renal data system database from 2002 to 2015 was used to validate and match patient cases of SLE with end stage renal disease after diagnosis. Patient race and ethnicity were recorded as listed in medical records.

Monitoring for CVD events began two years before diagnosis and continued for 13 years after diagnosis. Deaths from CVD events were defined as:

- Ischemic heart disease

- Cerebrovascular disease (including thrombotic and ischemic stroke, and transient ischemic attack)

- Peripheral vascular disease

Patients with baseline CVD were excluded from the study.

Results

A total of 336 patients diagnosed with SLE were included in the study and the mean age at diagnosis was 40 years. Selected patient characteristics can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Selected patient characteristics*

|

SD, standard deviation; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus. |

|

|

Characteristic, % (unless otherwise stated) |

All patients (n = 336) |

|---|---|

|

Racial groups |

|

|

White |

22 |

|

Black |

75 |

|

Asian |

3 |

|

Age at SLE diagnosis |

|

|

Mean age, years ± SD |

40 ± 17 |

|

<19 |

8 |

|

19 to <35 |

31 |

|

35 to <50 |

34 |

|

50 to <65 |

19 |

|

≥65 |

8 |

|

Sex |

|

|

Female |

87 |

|

Male |

13 |

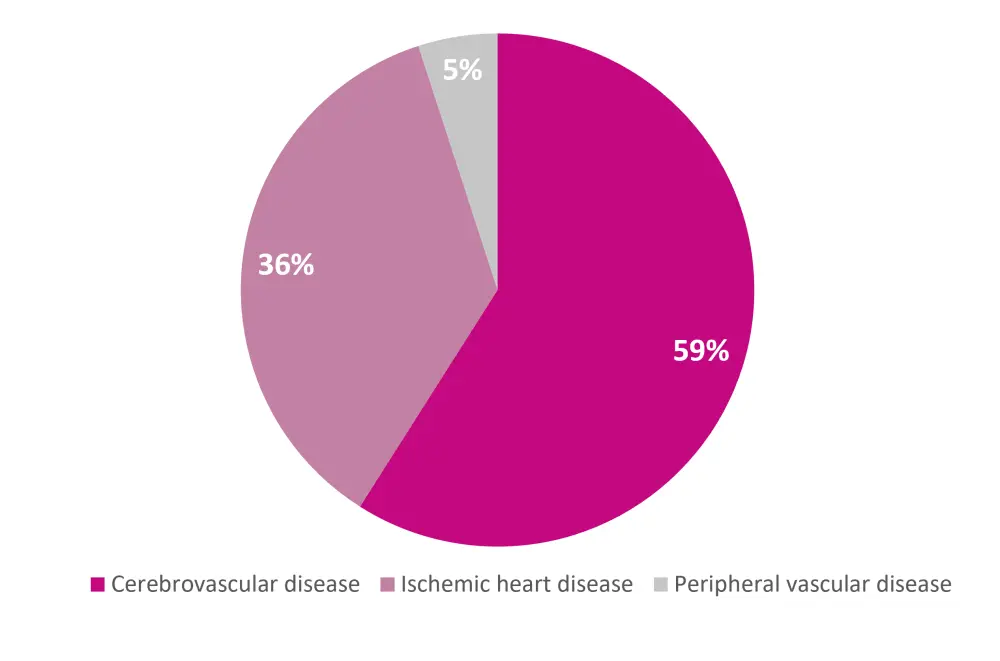

Overall, 56 (17%) patients were further diagnosed with incident CVD and specific cause of death was recorded (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CVD events in patients with SLE*

*Adapted from Garg, et al.1

The highest frequency of incident CVD occurred in the second year of diagnosis. In the first 12 years of diagnosis, 36 incident CVD events were recorded (31 women; 5 men). Notably, all but one event occurred in the Black patient cohort. A further 20 CVD events were identified in the final 3 years of the full 15-year surveillance period (18 women; 2 men), 17 of these were in Black patients and three in White patients.

Within the 4-year follow-up, the rate of strokes was higher in men and women diagnosed with SLE aged <40 years compared with the healthy population (2% and 3.9% vs 0.7% and 0.02%, respectively). Furthermore, there was a two times higher incidence of myocardial infarction and a seven times higher annual stroke rate in Black women diagnosed with SLE aged <55 years per 1,000 persons, compared with a healthy Black population (4.3% and 23% vs 2.3% and 2.9%, respectively).

Survival analysis

Differences in the timing of incident CVD stratified by race were investigated across the entire 15-year surveillance period.

- Analysis showed significantly increased incident CVD events in Black patients compared to non-Black patients with SLE (p < 0.0001).

- The sensitivity analysis which stratified Black and White racial groups showed a similar result (p < 0.0001).

- Competing risk analysis highlighted no statistical difference between cumulative incidence of CVD events.

- There was also no difference in cardiovascular related deaths compared to the cumulative incidence of non-CVD related deaths (p = 0.97).

Multivariable Cox model investigated the predictors of incident CVD and showed that:

- CVD rates in Black patients with SLE were 19-fold higher compared to non-Black patients with SLE in the first 12 years of the surveillance period (years -2 through 10) (p = 0.005).

- Over 15-year surveillance period, age ≥65 years at diagnosis (p = 0.01), renal disorder (p = 0.01) and discord rash (p = 0.002) diagnosis were all further predictors of CVD events.

A smaller Cox model, which was stratified by race, also highlighted that renal disorder, end stage renal disease, and age ≥65 years at diagnosis all remained predictors of CVD.

Multivariable analysis

Analysis showed Black patients with SLE had a seven times higher risk of CVD over a 15-year period compared to those in a healthy Black population. Again, age ≥65 years at diagnosis, renal disorder/end stage renal disease, and discoid rash were all multivariable predictors for higher CVD risk.

Conclusion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study investigating the risk, timing, and predictors of incident CVD events in a population predominantly comprising Black patients with SLE. This study has highlighted that CVD burden is 19-fold higher in Black patients with SLE, with the risk increasing from their second year of diagnosis. While discoid rash has been suggested as a new predictor for future CVD events, screening at a greater scope is needed and placing more emphasis on risk factor management could reduce disparities in patient outcomes.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content