All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The lupus Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lupus Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lupus and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lupus Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported through a founding grant from AstraZeneca. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lupus content recommended for you

Editorial theme | Trajectories of depressive symptoms in SLE

Do you know... Which factor was found to be significantly associated with Class 4, the group reporting the most severe depression in patients with SLE?

Neuropsychiatric manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have a significant impact on a patient’s quality of life (QoL). Patients with SLE are more than twice as likely to experience depressive episodes (95% confidence interval [CI], 29.9–40.3%) than the general population. Specific symptoms of lupus, such as the presence of cutaneous manifestations, treatment, and non-SLE issues (other health, social, and environmental factors), can all be linked to depressive symptoms.1

How depressive symptoms change over time and factors that may be associated with more severe depression has not been examined in patients with SLE. Our previous editorial theme articles have focused on the health-related quality-of-life in adolescent-onset and adult-onset SLE and the impact of SLE and lupus nephritis on a patient’s body image. In the final article in our series on QoL in patients with SLE, we will discuss the impact of depression on patient QoL over time and the risk factors associated with depression, summarizing findings from an article by Chawal et al.1

Study design

In this prospective study, data was collected during annual telephone calls to patients with SLE for up to 12 years. All patients included in this study met the revised American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria for SLE.

The Systemic Lupus Activity Questionnaire (SLAQ) was used to measure disease activity, with a high score indicating increased disease activity.

Depression was evaluated by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). CES-D is a self-reporting assessment tool that measures mood through 20 items. Each item is scored from 0 to 3, for a composite score of between 0 and 60; a CES-D score of ≥24 indicated depression. Physical functioning and bodily pain scores were assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 (SF-36) questionnaire with scores ranging from 0 (poor health) to 100 (ideal health).

Results

Patients in this study (N = 763) were split into four categories according to their CES-D score using a trajectory model:

- Class 1 had very low CES-D scores (36%)

- Class 2 had low CES-D scores (32%)

- Class 3 had scores around the threshold for depression (22%)

- Class 4 had high CES-D scores (10%)

The majority of patients were female (92.4%), the mean age was 50.1 years, and the mean duration of disease was 15.6 years. There was a slight increase in the number of Hispanic and African American patients in classes 3 and 4; additionally, patients in this class had a lower level of education and employment than those in classes 1 and 2 (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics*

|

IQR, interquartile range; SLAQ, Systemic Lupus Activity Questionnaire; SD, standard deviation; SF-36, Short-Form 36; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus. |

||||

|

Characteristic, % (unless stated |

Class 1 (n = 277) |

Class 2 (n = 241) |

Class 3 (n = 167) |

Class 4 (n = 78) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Female |

91.3 |

91.3 |

92.2 |

100.0 |

|

Mean age, years |

49.1 |

50.7 |

50.6 |

51.0 |

|

Deceased |

8.3 |

13.7 |

16.2 |

10.3 |

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

Caucasian |

72.2 |

73.0 |

71.4 |

68.5 |

|

Hispanic |

6.6 |

6.9 |

9.9 |

8.2 |

|

African American |

5.0 |

5.2 |

9.3 |

9.6 |

|

Asian |

11.2 |

8.2 |

5.6 |

6.8 |

|

Other |

5.0 |

6.9 |

3.7 |

6.8 |

|

Missing |

6.5 |

3.3 |

3.6 |

6.4 |

|

Education |

|

|

|

|

|

Less than high school |

0.4 |

1.7 |

9.0 |

2.0 |

|

High school graduate |

7.2 |

10.4 |

1.8 |

9.0 |

|

Some college |

24.5 |

31.1 |

31.1 |

26.9 |

|

Associate degree/ trade |

15.2 |

14.9 |

20.4 |

32.1 |

|

College graduate |

29.6 |

22.0 |

22.2 |

6.4 |

|

Graduate/ professional |

23.1 |

19.9 |

0.2 |

7.7 |

|

Employment status |

|

|

|

|

|

Employed |

62.5 |

46.5 |

33.5 |

21.8 |

|

Missing |

1.8 |

0.4 |

2.4 |

0 |

|

Income |

|

|

|

|

|

Above the poverty line |

93.0 |

93.3 |

84.0 |

69.2 |

|

Mean disease duration years |

15.9 |

15.9 |

14.9 |

15.6 |

|

Mean disease activity |

2.4 |

2.4 |

2.6 |

2.4 |

|

Mean SLAQ (IQR) |

2.5 (2.4) |

4.3 (2.4) |

5.3 (2.6) |

15.6 (8.6) |

|

SLE-induced renal issues |

15.2 |

22.0 |

23.4 |

32.1 |

|

Median SF-36 physical functioning (IQR) |

85 (60–95) |

60 (30–80) |

45 (25–60) |

30 (20–45) |

|

Median SF-36 bodily pain (IQR) |

50 (41–55) |

41 (33–46) |

37 (29–42) |

29 (25–37) |

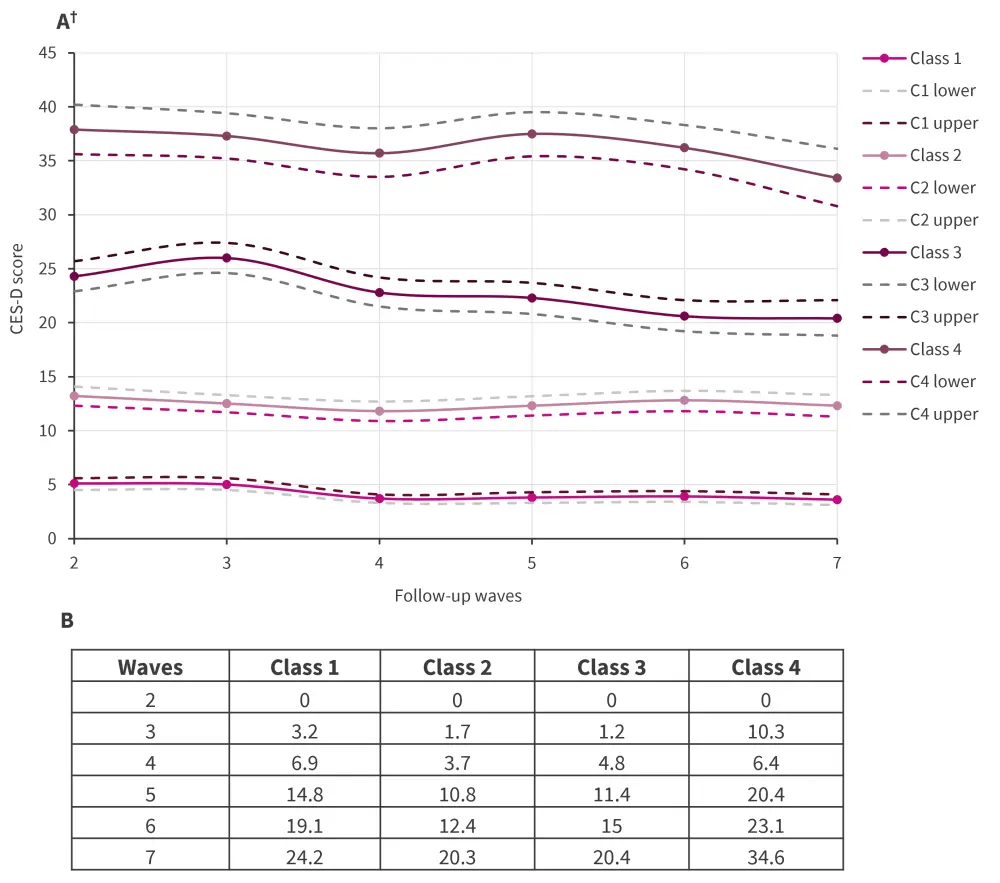

Patients usually remained in their original classes over the six waves of follow-up, whereas average CES-D scores showed small variations over time. There was also a decline in the number of patients over time, with Class 4 showing the highest level at 34.6% by follow-up wave seven (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A Mean depression scores over time and B percentage drop-out per group*

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

*Adapted from Chawla et al.1

†Dotted lines represent the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals of the CES-D score.

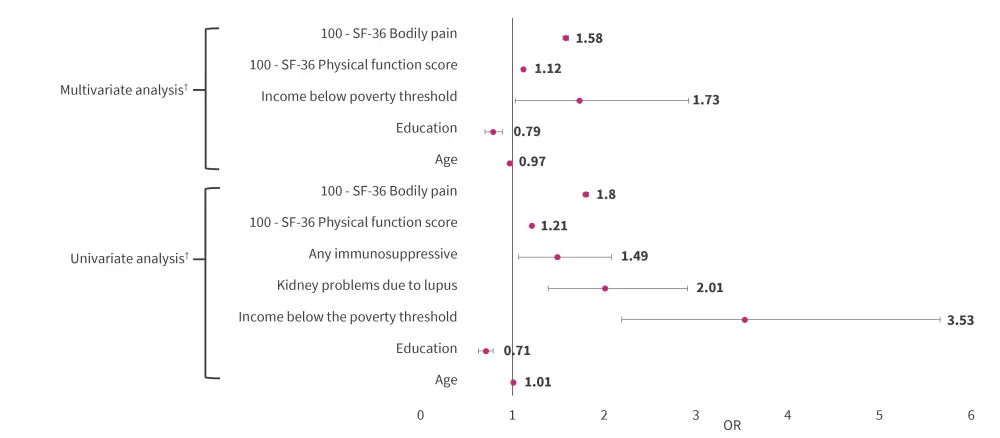

The odds ratios (OR) for different variables were examined for worse depression trajectories, as shown in Figure 2. Five categories were significant following multivariate analysis, including

- higher education levels (OR, 0.79; p = 0.0002);

- income below poverty threshold (OR, 1.73; p = 0.004);

- low SF-36 physical function score (OR ,1.12; p < 0.0001);

- low SF-36 Bodily pain score (OR, 1.58; p < 0.0001); and

- age (OR, 0.97; p = 0.0002).

Figure 2. Odds ratio estimates for significant variables (n = 581)*†

SF-36, short form-36.

*Adapted from Chawla et al.1

†Sample only includes patients with a posterior probability of >0.80.

Limitations

The authors noted several limitations of this study, including the lack of a depression diagnosis and the self-reported nature of the data, patients reported symptoms using the CES-D and SLAQ tools during telephone interviews, which may have biased the data. Some symptoms (fatigue and poor sleep) of depression and SLE overlap, which may elevate CES-D scores. Some effort was made to compensate for this by increasing the threshold for depression classification. Anxiety was not investigated and rate of patient drop-out during the study may have skewed the data.

Conclusion

In this prospective longitudinal study of patients with SLE, age and income level were associated with lower CES-D depression scores. This study had a median duration of disease of 15.6 years; however, further research investigating the trajectory of depression scores from the time of SLE diagnosis could provide further insight. Income level below the poverty line, low SF-36 bodily pain scores and low SF-36 physical functioning scores were also associated with higher depression scores.

Recognizing the importance of these risk factors may facilitate improved screening of patients with SLE and enable more effective targeting of mental health support.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content