All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The lupus Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lupus Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lupus and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lupus Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported through a founding grant from AstraZeneca. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lupus content recommended for you

Editorial theme | Impact of SLE and LN on patients’ QoL and body image

Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can be at risk of anxiety and depression due to the impact of their symptoms on their daily life, physical functioning, and fear about the future.1,2 However, which symptoms are most burdensome and whether having lupus nephritis (LN) adds to this risk is unclear. In addition, SLE may cause visible signs of disease, such as skin rashes and alopecia, which can cause body image disturbance (BID) in patients, but how great an impact this has on a patient’s quality of life (QoL) remains to be examined.1,2

This editorial theme article will examine the impact of LN and SLE on QoL, summarizing the findings of Hu and Zhan,1 published in Immunity, Inflammation and Disease, and Chen et al.2 published in BMJ Open.

This is the second editorial theme article in a series exploring QoL in patients with SLE. The first article in this series was on health-related QoL in adolescent and adult-onset SLE and can be found here.

Impact of LN and SLE on QoL1

Study design

To investigate the impact of SLE and LN on QoL, 150 patients were enrolled in a case control study that included patients with SLE and LN (LN cohort; n = 50), patients with SLE but not LN (non-LN SLE cohort; n = 50), and healthy controls (HC cohort; n = 50). Patients were assessed for anxiety and depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) following enrolment on to the study. HADS for anxiety (HADS-A) was used to assess a patient’s anxiety level and a score >7 was considered to indicate anxiety. HADS for depression (HADS-D) was used to assess depression in patients and a score >7 was taken to indicate depression.

Eligibility criteria for patients with LN included:

- Diagnosed as LN according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria

- Aged >18 years

Exclusion criteria included:

- A history of hematologic malignant disease or cancer

- Pregnancy or lactating

Results

Patient characteristics were only provided for the LN cohort (Table 1). Patients had a median disease duration of 55.5 months and 44% were classified as having Class IV LN.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients with SLE and LN*

|

IQR, interquartile range; LN, lupus nephritis; SD, standard deviation; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SLEDAI, systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index. |

|

|

Characteristic, % (unless otherwise stated) |

LN cohort (n = 50) |

|---|---|

|

Mean age ± SD, years |

46.3±16.7 |

|

Sex |

|

|

Female |

86.0 |

|

Male |

14.0 |

|

Median disease duration (IQR), months |

55.5 (2.0–122.0) |

|

Median SLEDAI score (IQR) |

9.0 (6.0–15.8) |

|

LN classification |

|

|

Class II |

10.0 |

|

Class III |

12.0 |

|

Class IV |

44.0 |

|

Class V |

10.0 |

|

Class V+III |

8.0 |

|

Class V + IV |

16.0 |

|

Median LN activity index (IQR) |

8.0 (5.0–10.0) |

|

Median LN chronicity index (IQR) |

3.0 (2.0–4.0) |

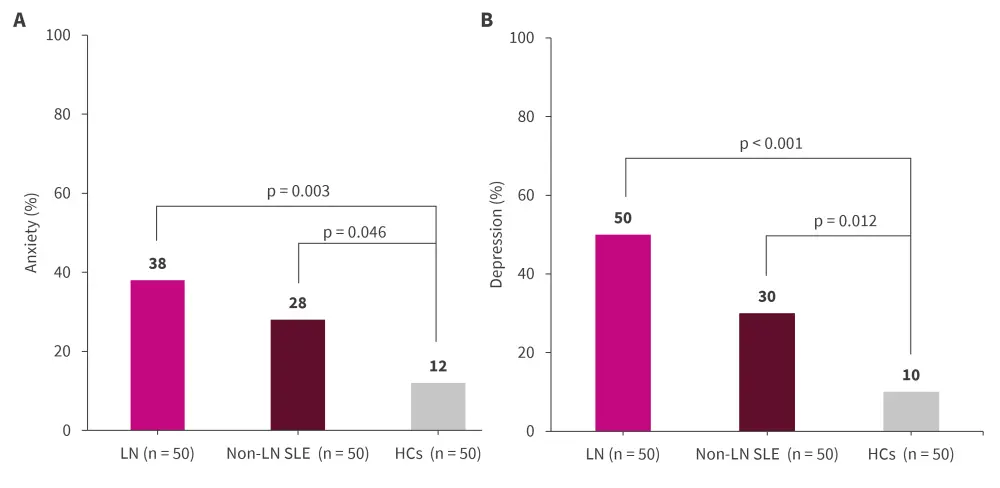

There was a significantly higher rate of anxiety (HADS-A >7) in patients with LN compared with the HCs (p = 0.003; Figure 1). Patients with non-LN SLE also experienced significantly increased rates of anxiety, but this was less than in the LN group (p = 0.046). A similar trend was seen with respect to depression.

Figure 1. Rates of A anxiety and B depression*

HC, healthy control; LN, lupus nephritis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

*Adapted from Hu and Zhan.1

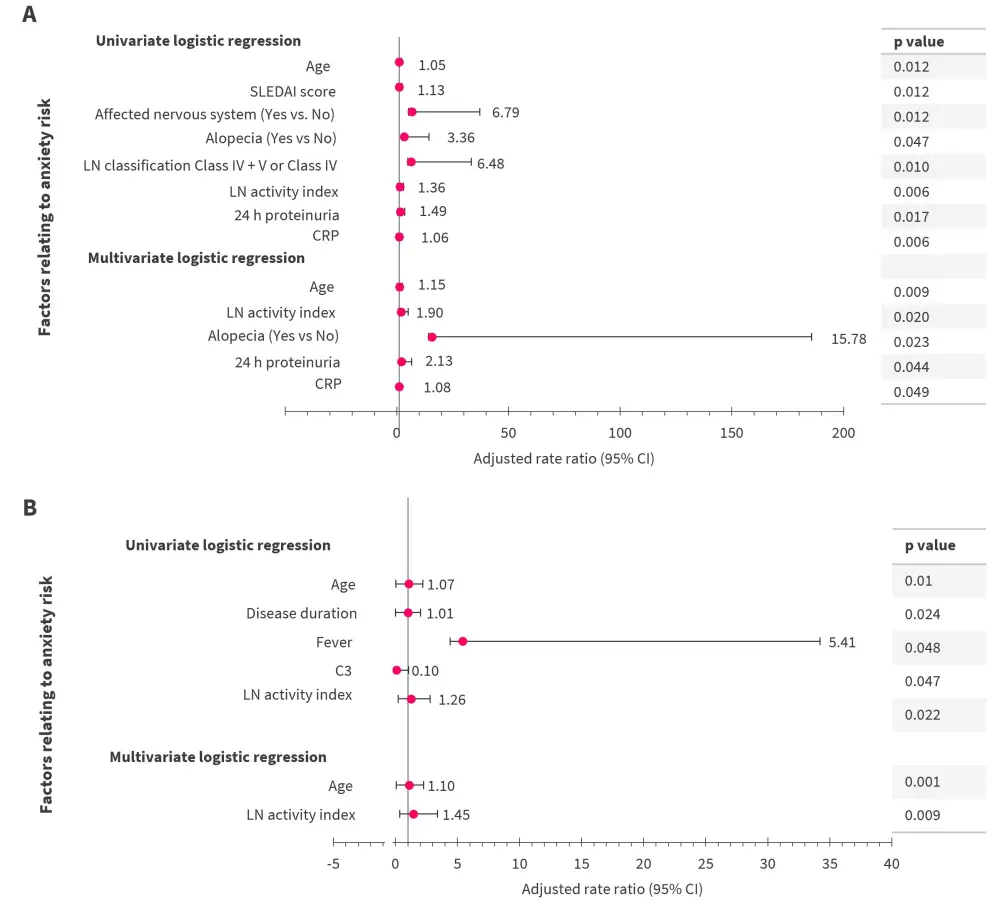

Factors that were associated with an increased risk for anxiety and depression were also investigated across the whole cohort and the factors that were found to be significant are shown in Figure 2. Age, LN activity index, whether a patient had alopecia, 24-hour proteinuria, and c-reactive protein (CRP) remained significantly associated with increased risk for anxiety following multivariate analysis.

The only factors that were significantly associated with depression following multivariate analysis were age (p = 0.001) and LN activity index (p = 0.009; Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Significant factors relating to A anxiety and B depression according to univariate and multivariate analyses*

CI, confidence interval; CRP, c-reactive protein; LN, lupus nephritis; SLEDAI, systematic lupus erythematosus disease activity index.

*Adapted from Hu and Zhan.1

The HADS-A score was found to be significantly correlated with LN classification (p = 0.021) while the same was not true for the measure of depression, HADS-D.

Limitations

This study was limited by its small sample size and due to it being a single-center study. The HADS scores were subjective and filled out by the patient so may be liable to bias.

Impact of SLE on body image2

Study design

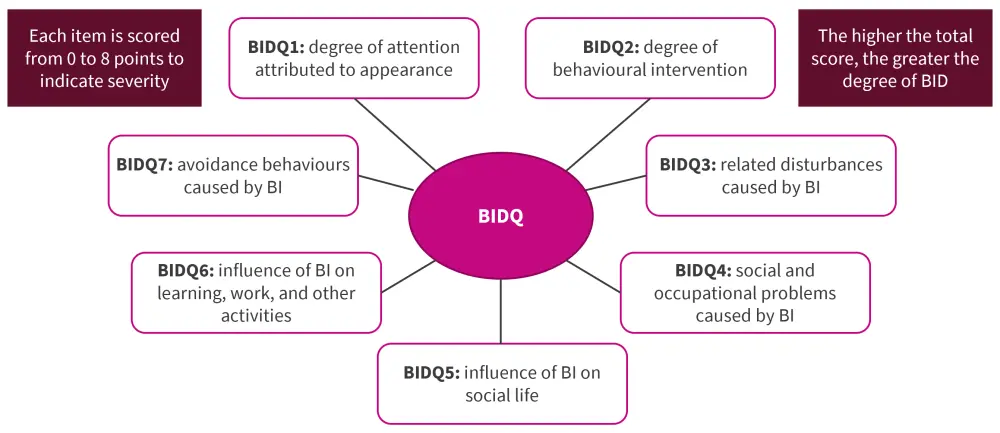

Patients with SLE (n = 230) were given a BID questionnaire (BIDQ; scoring system shown in Figure 3) to assess the impact SLE had on their BI. In addition, the HADS tool, the Multi-Dimensional Fatigue Inventory-20 (MFI-20), Body Image Quality of Life Inventory (BIQLI), and systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index (SLEDAI) were used to assess anxiety and depression, fatigue, BID with QoL, and disease activity, respectively.

Eligibility criteria included:

- Patients meeting the 1997 ACR revised criteria for the classification of SLE

- Aged ≥18 years

- Disease duration >6 months

Figure 3. BID questionnaire scoring system*

BU, body image; BID, body image disturbance; BIDQ, body image disturbance questionnaire.

*Data from Chen, et al.2

There was a 93.48% response rate to the questionnaires. The majority of patients were female and >50% were aged 18−35 years. Most patients had no SLEDAI score (62.79%) and 30.7% had comorbidities (Table 2). Correlations of the variables shown in Table 2 with BID were assessed and significant correlations were found for education level, comorbidities, and SLEDAI scores.

Results

Table 2. Patient characteristics*

|

BMI, body mass index; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SLEDAI, systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index. |

|||

|

Characteristic |

Percentage |

r |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Sex |

|

0.063 |

0.359 |

|

Female |

97.67 |

|

|

|

Male |

2.33 |

|

|

|

Age, years |

|

−0.08 |

0.243 |

|

18−35 |

52.1 |

|

|

|

36−60 |

45.58 |

|

|

|

60 |

2.32 |

|

|

|

BMI, kg/m2 |

|

0.025 |

0.715 |

|

<18.5 |

11.16 |

|

|

|

18.5−24.9 |

72.1 |

|

|

|

>24.9 |

16.74 |

|

|

|

Marital status |

|

0.094 |

0.169 |

|

Married |

82.33 |

|

|

|

Education level |

|

0.17 |

0.012† |

|

>9 |

50.7 |

|

|

|

Employment |

|

−0.119 |

0.081 |

|

Yes |

54.42 |

|

|

|

Income |

|

0.004 |

0.953 |

|

<¥15,000 |

28.37 |

|

|

|

¥15,000–¥33,000 |

47.91 |

|

|

|

>¥33,000 |

23.72 |

|

|

|

Tobacco use |

|

−0.067 |

0.327 |

|

No |

98.6 |

|

|

|

Alcohol use |

|

|

|

|

No |

97.21 |

|

|

|

Exercise |

|

|

|

|

No |

60.47 |

|

|

|

Clinical factors |

|

|

|

|

Course of disease |

|

0.005 |

0.945 |

|

≤3 years |

30.7 |

|

|

|

3−10 years |

47.44 |

|

|

|

>10 years |

21.86 |

|

|

|

Comorbidities |

|

0.265 |

<0.001§ |

|

Yes |

30.7 |

|

|

|

SLEDAI |

|

0.208 |

0.002‡ |

|

No |

62.79 |

|

|

|

Mild |

26.05 |

|

|

|

Moderate |

9.3 |

|

|

|

Severe |

1.86 |

|

|

|

Use of NSAIDs |

|

0.003 |

0.961 |

|

≤7.5mg/day |

80 |

|

|

With all scoring systems except BIQLI, a higher score meant increased severity in the item being measured. The BIQLI score when positive can be interpreted as a positive effect, zero indicates no effect, and negative is read as a negative effect. The results of these measures of anxiety, depression, fatigue, and BID are shown in Table 3, with patients with SLE having a mean BIDQ score of 23.04. Patients gave physical fatigue the highest score out of the different measures of fatigue (27.06).The BIQLI results had three elements with a negative mean score, including self-evaluation, relationship, and emotional.

Table 3. Anxiety and depression, MFI-20, BIDQ, and BIQL scores*

|

BID, body image disturbance; BIQLI, Body Image Quality of Life Inventory; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MFI20, Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory-20; SD, standard deviation; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus. |

|||

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Min, max |

|---|---|---|---|

|

BIDQ |

23.04 |

11.90 |

0, 54 |

|

HADS-A |

6.94 |

4.53 |

0, 21 |

|

HADS-D |

6.49 |

4.51 |

0, 21 |

|

Fatigue |

|

|

|

|

Physical fatigue |

27.06 |

6.29 |

13, 39 |

|

Mental fatigue |

11.14 |

3.03 |

4, 18 |

|

Power drop |

8.31 |

2.87 |

3, 15 |

|

Reduced activity |

7.70 |

2.64 |

3, 15 |

|

MFI-20 |

54.21 |

11.63 |

26, 81 |

|

BIQLI |

|

|

|

|

Self-evaluation |

−0.24 |

5.22 |

−12, 12 |

|

Relationship |

−0.47 |

5.95 |

−18, 18 |

|

Emotional |

−0.55 |

4.20 |

−9, 9 |

|

Lifestyle |

1.49 |

5.92 |

−15, 15 |

|

BIQLI |

0.31 |

16.59 |

−51, 51 |

Correlation between BID and HADS-A, HADS-D, MFI-20 and BIQLI were assessed and BID was found to be significantly correlated with all scores (p < 0.01 for HADS-A, HADS-D, and MFI-20; and p < 0.05 for BIQLI dimensions).

Predictors of BID were analyzed and included:

- MFI-20 (p < 0.001)

- HADS-D (p < 0.001)

- Comorbidities (p < 0.01)

- SLEDAI (p < 0.05)

Conclusion

Anxiety and depression levels were found to be highest in patients with LN and SLE, followed by patients with non-LN with SLE, compared with HCs, in the study by Hu and Zhan.1 The factors that increased the risk of anxiety included aging, higher LN activity score, 24-hour proteinuria, CRP, and alopecia, while depression risk was impacted by age and LN activity score.

Possible explanations as to why these factors increase anxiety could include the following:

- As people age, mobility decreases and the number of comorbidities tends to increase. This makes symptoms harder to manage and causes patients to have to rely on help from family or external organizations, which in turn may incur increased costs. All of this may lead a patient to feel less in control of their life and leave them vulnerable to anxiety and depression.

- CRP as a marker of systemic inflammation and ongoing inflammation may be associated with increased susceptibility to anxiety and depression. This association has been noted in previous studies.3,4

- Alopecia can cause a dramatic change in a person’s appearance and may make patients less confident at social events or at work. As a result, experiencing alopecia can increase the risk of depression and anxiety.

- More severe LN could be associated with increased anxiety and depression as it could reduce a patient’s ability to do their normal daily and social tasks. Anxiety related to progression of LN could also be a factor.

Changes in physical appearance and functioning can be a great concern to patients with SLE and impact BI. In the study by Chen et al.2, BID was found in patients with SLE and was significantly correlated with depression, disease activity, fatigue, and presence of comorbidities. As part of the management of SLE, it is important to be aware of these factors and understand that patient’s experiencing BID may show avoidant behaviors, while experiencing increased fatigue and disability. Interventional measures to assist patients with BI, alongside the management of the physical symptoms of SLE, could increase a patient’s QoL.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content