All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The lupus Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lupus Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lupus and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lupus Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported through a founding grant from AstraZeneca. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lupus content recommended for you

Clinical considerations in the diagnosis and management of systemic lupus erythematosus

Do you know... Which of the following is most clinically associated with drug-induced lupus?

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex disease, with variable presentation and disease progression, making it challenging to diagnose and manage.1 However, the last few decades have seen significant progress in our understanding of the disease, the underlying pathophysiology and genetics, and the criteria to help diagnose and classify the disease. Published in Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology in January 2022, Xin Huang and colleagues1 provided a comprehensive review in which they considered the latest developments and research in SLE. Here, we provide a summary of the publication.

Incidence and demographics

SLE is recognized to be life-limiting and life-threatening during acute episodes, with a 2.6-fold increased risk of mortality in patients with SLE. The incidence varies from 0.3/100,000 person years to 23.2/100,000 person years in different countries, with variation arising from differences in genetic, socioeconomic, and environmental factors. Women of reproductive age are acknowledged to be at increased risk of SLE especially, with a female-to-male ratio estimated to be between 8:1 and 15:1.

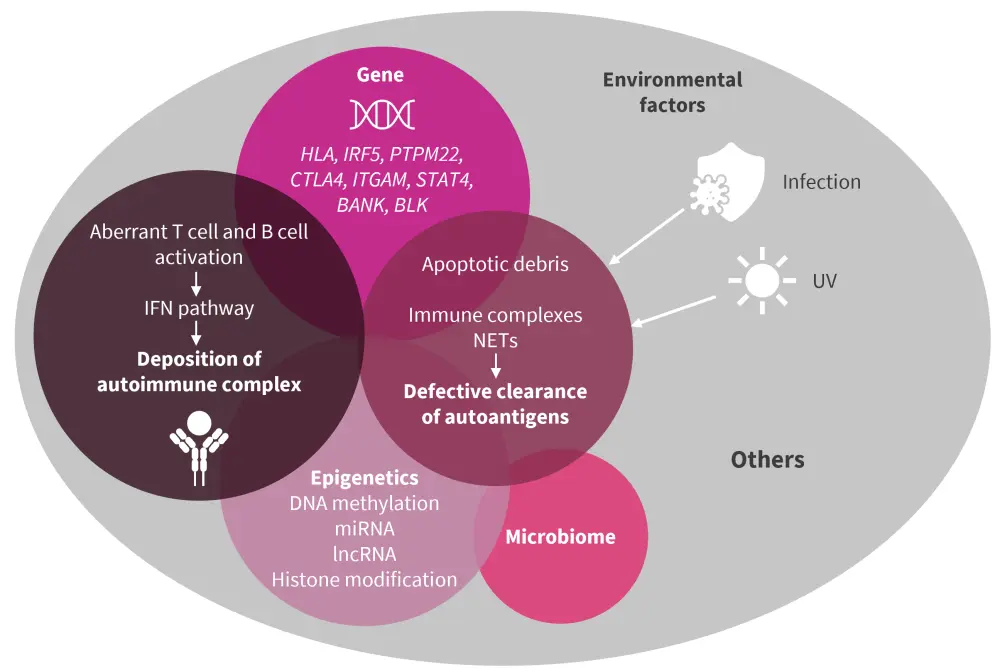

Pathophysiology of SLE

The pathophysiology of SLE is multifactorial, including genetic predisposition, epigenetic factors, immune dysregulation, abnormal gene expression, environmental risk factors and drivers, and loss of normal homeostasis. Ineffective removal of the waste products of apoptosis, immune complexes and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), impaired lymphocyte function, and stimulation of the interferon (IFN) pathway leads to the production of active autoimmune complexes. These complexes persist within the body, accumulate, and can spread to other areas where they are deposited in other organs and tissues, leading to subsequent localized inflammation and involvement (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Genetic and immune mechanisms underlying SLE*

IFN, interferon; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; miRNA, microRNA; NET, neutrophil extracellular trap; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; UV, ultraviolet.

*Adapted from Huang, et al.1

The disease process also features circulating autoantibodies, which target self-tissue. The most frequently detected autoantibodies are anti-nucleosome and RNA-binding protein antibodies. Following exposure to environmental triggers, apoptosis is initiated and often accelerated, with overproduction of nucleic debris and NETs. Particular antibodies, such as anti-nuclear antibodies and anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies, are strongly associated with SLE, as well as other autoimmune conditions, and have roles in diagnosis, prognostication, prediction of disease course, and monitoring for response to treatment (Table 1).

Table 1. Autoantibodies with clinical association to SLE*

|

SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus. |

||

|

Antibody |

Abbreviation |

Associations |

|---|---|---|

|

Anti-nuclear antibody |

ANA |

Strong association, but not specific to SLE |

|

Anti-double-stranded DNA antibody |

Anti-dsDNA |

Strongly associated with disease activity |

|

Anti-smooth muscle antibody |

Anti-Sm |

Highly specific antibody for SLE |

|

Anti-Sjögren's syndrome-related antibody |

Anti-SSA |

Associated with photosensitivity, ANA-negative SLE, and neonatal SLE |

|

Anti-U1 ribonucleoprotein antibody |

Anti-U1-RNP |

Marker of mixed connective tissue diseases |

|

Anti-histone antibody |

— |

Associated with drug-induced lupus |

|

Anti-ribosomal antibody |

— |

Associated with early onset of disease, occurrence of skin erythema, and diffuse neuropsychiatric events |

|

Anti-phospholipid antibody |

APLA |

Indicator of vascular inflammation, thromboembolic risk, and increased risk of neuropsychiatric events |

Genetic factors involved in the pathogenesis of SLE include human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex and genes related to T-cell activation and IFN pathways. Two HLA regions in particular carry SLE-associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms (HLA-DRB1 and HLA-DR3). In addition, other SLE-associated gene polymorphisms are seen in the genes listed below:

- IRF5

- PTPM22

- BANK

- BLK

- STAT4

- ITGAM

- CTLA4

However, in addition to the polymorphisms, environmental factors, such as ultraviolet (UV) light, infections, drugs, toxins, and diet, are required to drive the pathological process underlying SLE.

Other epigenetic processes, such as abnormal DNA methylation and aberrant RNA expression, are also involved in triggering the onset of SLE. Aberrant T-cell and B-cell activation and dysregulation of the IFN pathway, as a result of demethylation of genes, can lead to autoimmune disease. Furthermore, SLE can be induced in murine models with DNA-methylating inhibitors, such as azacitidine

In addition to the mechanisms described above, altered immune physiology is well established in the pathology of SLE, in particular the abnormal activity of immune mediator cells. This includes T-cell overactivity, impaired B-cell selection and clonal expansion, and loss of immune tolerance leading to a systemic state of autoinflammation. T helper and follicular helper cell populations become markedly increased, with a decrease in T regulating cells, which leads to an attenuated immune response.

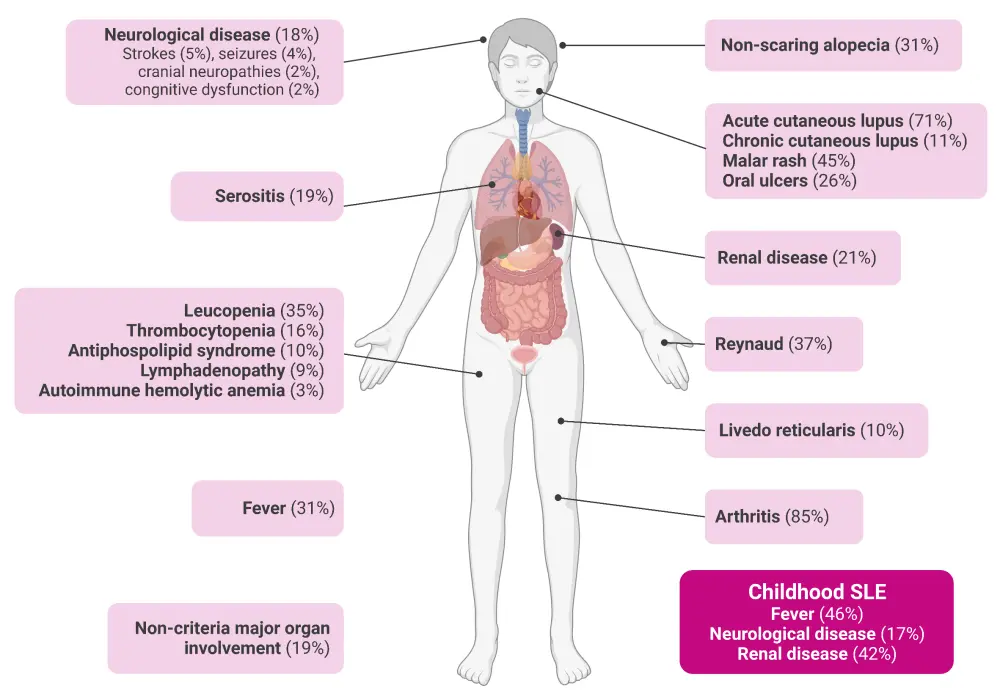

Presentation and clinical symptoms

The clinical symptoms of SLE vary greatly between individuals and share common features with other diseases, including other rheumatological conditions, infections, and hematologic conditions and malignancies. The skin, joints, muscles, kidneys, and blood vessels are most commonly affected in SLE (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Clinical manifestations of SLE*

SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

*Adapted from Fanouriakis, et al.2 Created with BioRender.com.

Diagnosis and classification of SLE

The diagnosis of SLE is complicated by its variable presentation, clinical heterogeneity, unpredictable disease course, and interpatient variation in the pattern, severity, and variation of flares. Although widely accepted as a systemic disease, SLE can be organ-dominant, both in terms of presentation and progression. SLE remains a clinical diagnosis, with some seronegative cases in whom diagnosis is dependent on the recognition of the disease manifesting in different organs and tissues (Table 2).

Table 2. Manifestations of SLE in different organ systems*

|

CLE, cutaneous lupus erythematosus. |

|

|

Organ/tissue |

Common manifestations |

|---|---|

|

Skin |

Can be isolated (i.e., CLE) or associated with systemic disease |

|

Kidney |

Strong predictor of morbidity and mortality |

|

Hematological system |

Leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, autoimmune haemolytic anaemia, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura |

|

Musculoskeletal |

SLE-related synovitis generally affects more than two joints |

|

Neuropsychological events |

Headache, mood disorders such as depression and anxiety, cognitive impairment, seizures, cerebrovascular disease, psychosis, myelopathy, aseptic meningitis, and peripheral nervous system involvement |

|

Pulmonary |

Asymptomatic pleural effusion/pleuritis, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and diffuse alveolar haemorrhage |

|

Cardiac |

Pericarditis, valvular heart disease, myocarditis, thrombosis, and arrhythmias |

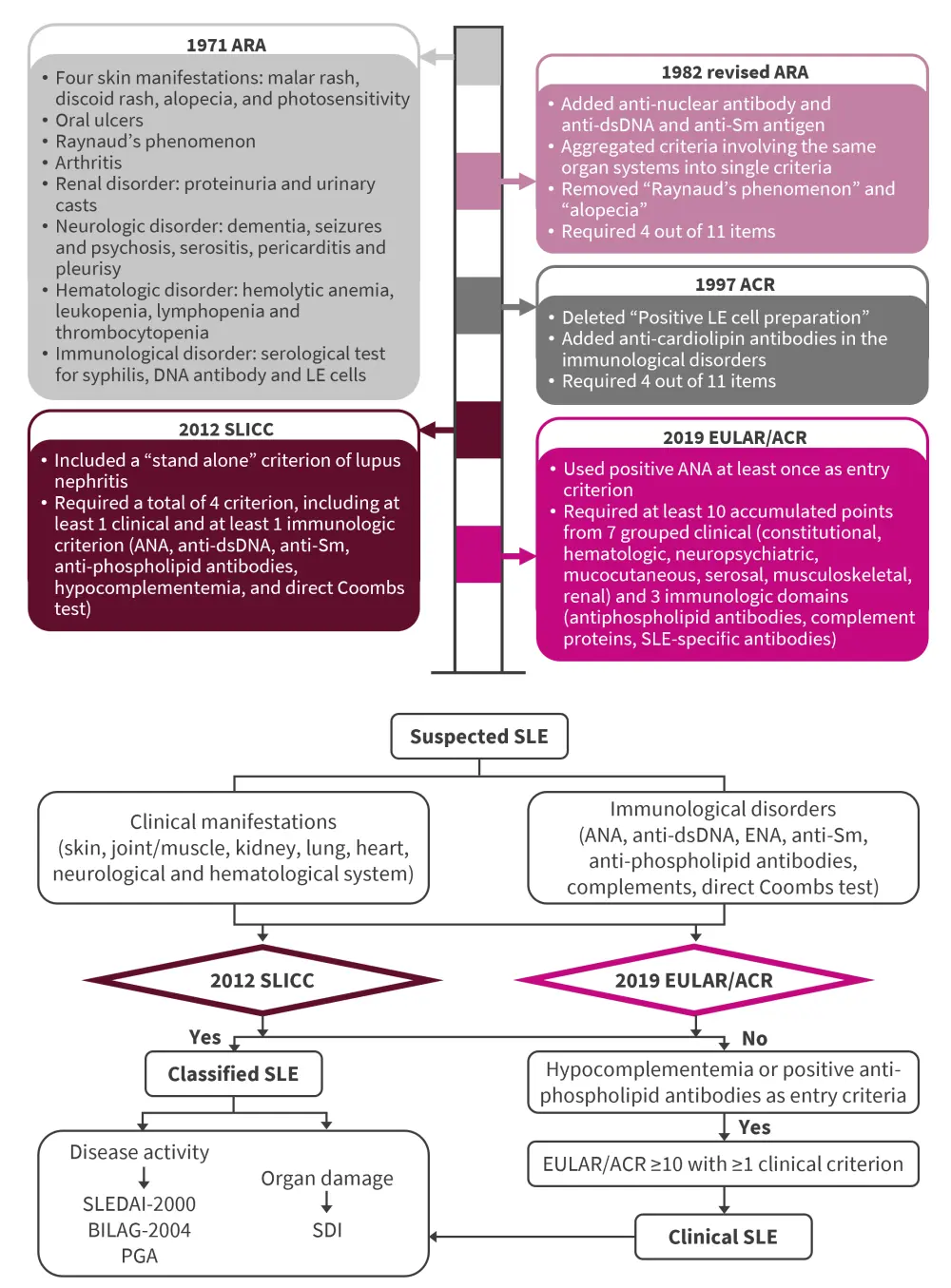

It is this complex clinical presentation and diagnosis of SLE that makes it a difficult disease to define. Classification criteria are essential to improve diagnostic accuracy and to facilitate homogeneous grouping of patients for inclusion in research studies and trials. Since the first classification criteria produced in 1971 by the American Rheumatology Association, multiple classification criteria have been produced, each evolving from the previous one (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Progression of SLE classification criteria from 1971 to 2019 and details of the 2012 and 2019 guidelines on the diagnosis of SLE*

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; ANA, antinuclear antibody; anti-Sm, anti-Smith; ARA, American Rheumatism Association; BILAG-2004, 2004 British Isles Lupus Activity Group; dsNA, double-strand DNA; ENA, extractable nuclear antigen; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; PGA, Physician Global Assessment; SDI, SLICC/ACR Damage Index; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SLEDAI-2000, SLE Disease Activity Index-2000; SLICC, Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics.

*Adapted from Huang, et al.1

Autoimmune changes can occur up to a decade before clinical manifestations of SLE. The most common symptoms reported before or within the first 12 months following diagnosis are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3. Symptoms reported in the first 12 months following diagnosis*

|

*Data from Huang, et al.1 |

|

|

Symptom |

Frequency, % |

|---|---|

|

Fatigue |

89.4 |

|

Joint pain |

86.7 |

|

Photosensitivity |

79.4 |

|

Myalgia |

76.1 |

|

Skin rash |

70.5 |

Treatment of SLE

The aims of treatment include the reduction of disease activity, remission of disease symptoms, management of acute flares, minimization of drug side effects, and prevention of damage accrual. This involves patient and family education and counselling on the signs and symptoms of disease progression, early recognition of acute flares, and treatment adherence and compliance, with the ultimate aim of maximizing quality of life and survival.

The Lupus Hub has previously reviewed the management and treatment of SLE and lupus nephritis.

Comorbidities and disease risk

Patients with SLE are at an increased risk of infection, due to both disease-related factors (e.g., leukopenia) and treatment-related factors (e.g., glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants). Patients with SLE also have an increased risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, osteoporosis, cancer, other autoimmune diseases, and drug toxicities. In terms of malignancy, patients with SLE are at a greater risk of hematologic, cervical, lung, liver, and breast cancers, among others.

Those diagnosed with SLE during childhood are at the greatest risk of significant comorbidities, including stroke, myocardial infarction, neurological problems, arthroplasty, and renal transplant, and they have worse organ involvement and accrue tissue damage more quickly.

Future challenges

A major challenge in the diagnosis of SLE remains the lack of widely accepted and utilized classification and diagnostic criteria, including those specifically for atypical, preclinical, and child-onset SLE. Further research in these areas will enable earlier targeted treatment and could prevent progression of the disease.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content