All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The lupus Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lupus Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lupus and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lupus Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported through a founding grant from AstraZeneca. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lupus content recommended for you

Management of general systemic lupus erythematosus

Do you know... Belimumab is a biologic agent used for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. A patient with which of the following disease characteristics would be mostly likely to benefit from treatment?

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has a variable presentation and prognosis, which makes it challenging to diagnose and manage. Presentation may vary between multisystemic or occasionally organ-specific1 and may occur any time between childhood and late adulthood (late onset SLE)2. As a result, treatment needs to be tailored to the patient depending on these factors, along with reproductive status.

In 2008, the first European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) recommendations for the management of SLE were published. New data since then necessitated an update, which was published in 2019.1 This article summarizes the 2019 recommendations, along with recent developments from subsequent clinical trials. This article will focus on extrarenal management of SLE and an accompanying article, which can be found here, will focus on the management of lupus nephritis (LN).

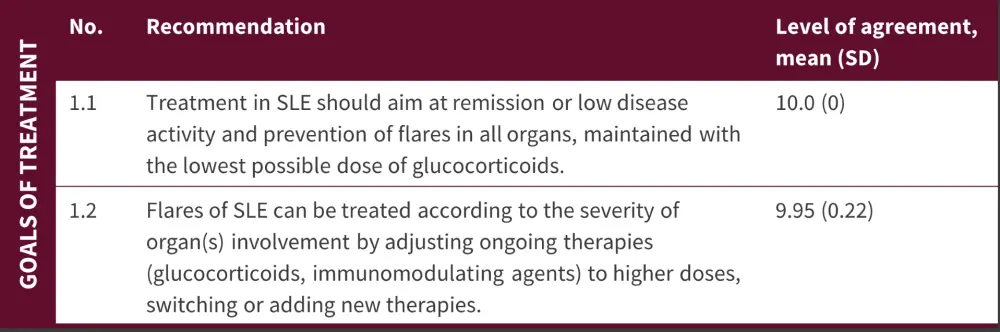

Goals of therapy

Complete remission of SLE is rarely achieved; therefore, the main goal of therapy is low disease activity, prevention of damage accrual, and the reduction of therapeutic side effects while improving quality of life. Low disease activity is defined as a Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) score ≤3 on antimalarials, or SLEDAI ≤4, a physician global assessment ≤1 with glucocorticoids (GCs; ≤7.5 mg prednisone), and immunosuppressive agents that are well tolerated. Low disease activity has shown similar results compared with remission with respect to damage accrual and prevention of SLE flare-ups. The EULAR recommendations for treatment goals are listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Goals of treatment*

SD, standard deviation; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

*Adapted from Fanouriakis, et al.1

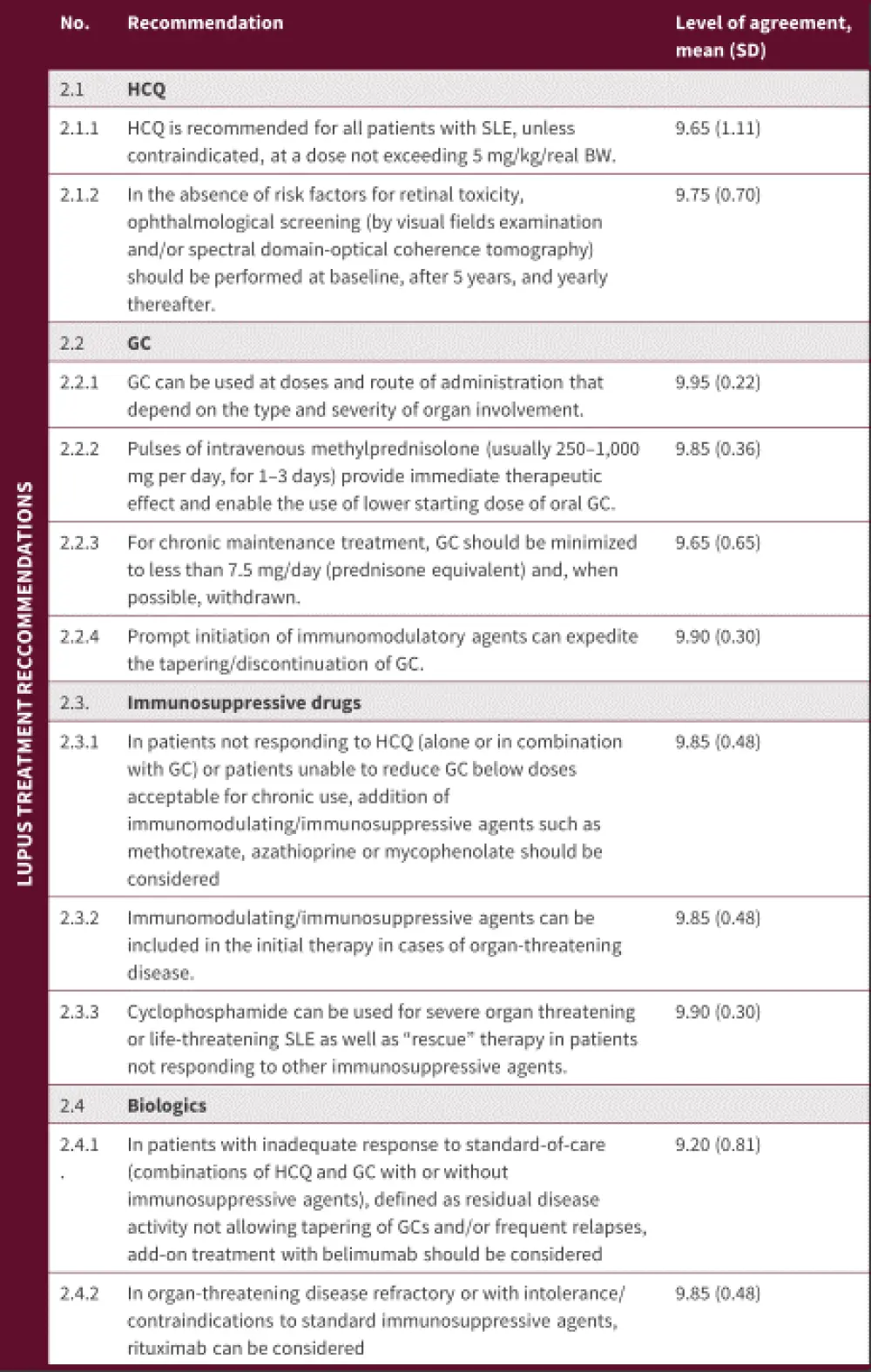

Treatment of lupus

The EULAR recommendations for treatment of lupus are summarized in Figure 2

Figure 2. Lupus treatment recommendations*

BW, body weight; GC, glucocorticoids; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; SD, standard deviation; SLE, systematic lupus erythematosus.

*Adapted from Fanouriakis, et al.1

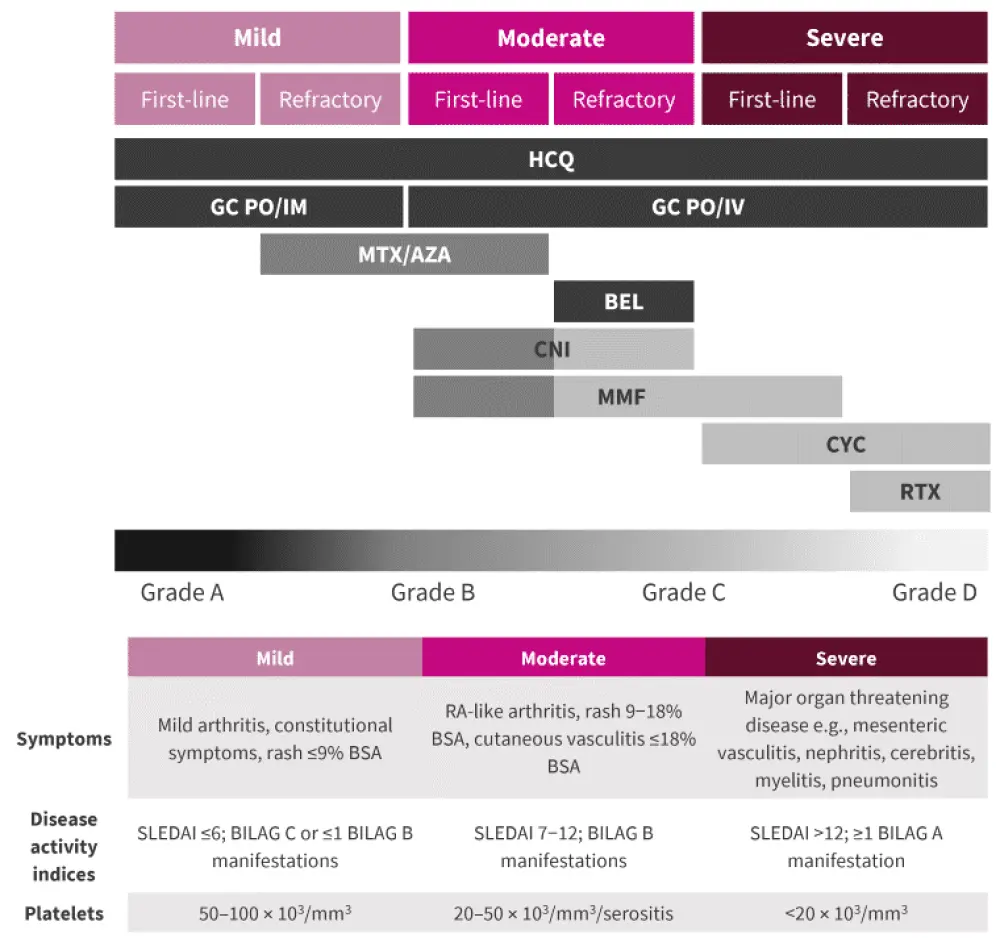

A summary of the management of patients with SLE is shown in Figure 3, with definitions of each category of severity also shown.

Figure 3. Lupus treatment overview*

BEL, belimumab; BILAG, British Isles Lupus Assessment Group Disease Activity Index; BSA, body surface area; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; CYC, cyclophosphamide; GC, glucocorticoids; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MTX, methotrexate; PO, per os; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RTX, rituximab; SLEDAI, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index.

*Adapted from Fanouriakis, et al.1

Hydroxychloroquine

The EULAR 2019 guidelines recommend hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) for all patients with SLE. Despite the many benefits associated with HCQ, treatment adherence may be poor. The main side effect of concern with HCQ use is retinopathy, and ophthalmological screening is recommended (Figure 2).

The main risk factors for retinopathy include:

- Treatment duration (odds ratio [OR], 4.71 for every 5 years use)

- Dose (OR, 3.34 for every 100 mg daily dose)

- Chronic kidney disease (adjusted OR, 8.56)

- Pre-existing retinal or macular disease (OR, not given)

A dose of <5 mg/kg is recommended for minimizing retinopathy; however, this is lower than the 6.5 mg/kg used to establish the efficacy of HCQ and no studies have confirmed the clinical benefit of HCQ at this dose. Quinacrine may be considered in patients with cutaneous disease and in cases of HCQ-induced retinal toxicity.

Glucocorticoids

As GCs can cause irreversible organ damage if used long-term, dosage should be limited to ≤7.5 mg/day prednisone or equivalent. Two tapering/discontinuation approaches can be considered to further minimize GC use and organ damage:

- Varied pulsed doses of intravenous methylprednisolone (dependent on disease severity and patient body weight)

- Early use of immunosuppressive agents

Immunosuppressive agents

Starting treatment with immunosuppressive agents may allow for earlier GC tapering and prevent flares of SLE. Agents commonly considered include azathioprine, methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil. Greater efficacy has been seen with methotrexate over azathioprine but the latter is more suitable if a patient is considering becoming pregnant. Mycophenolate mofetil is a potent immunosuppressant that is effective in both SLE and LN, but it is costly and due to its teratogenic potential, treatment should be stopped ≥6 weeks prior to conception. Recommendations for their use are described in Figure 2 and illustrated in Figure 3. Cyclophosphamide is recommended only for organ-threatening disease and is frequently used with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues to reduce negative effects on the ovarian reserve.

Biologics

B-cell targeting agents have shown promise for the treatment of SLE with belimumab recommended for inadequately controlled extrarenal SLE. Patients who are more likely to respond to belimumab have severe disease (SLEDAI >10), >7.5 mg/day GC dose, and serological activity such as low levels of C3/C4 or high anti-double stranded DNA titers.

Rituximab has had negative results in clinical trials therefore it is only used off label in severe LN or SLE that is refractory to other agents.

Organ-specific manifestations

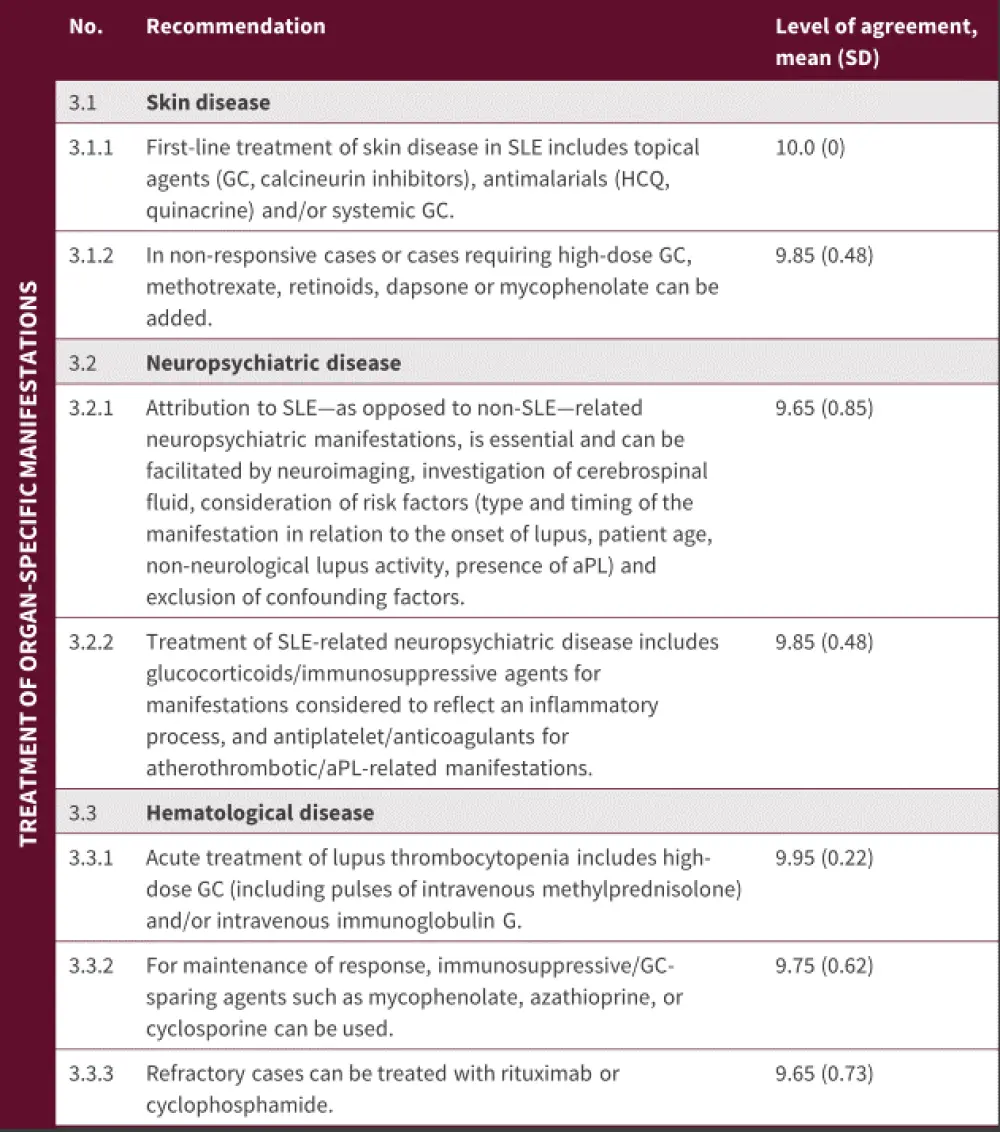

Figure 4. Treatment of organ-specific manifestations*

aPL, antiphospholipids; GC, glucocorticoids; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; SD, standard deviation; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

*Adapted from Fanouriakis, et al.1

Cutaneous SLE

Effective broad spectrum ultraviolet sun cream and stopping smoking are strongly recommended for patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Recommendations for treatment are shown in Figure 4, with first-line treatment focused on topical agents and antimalarials, with or without systemic GCs. Almost 40% of patients do not respond to initial lines of therapy and in these patients, methotrexate is recommended as the next option. Thalidomide may be effective for cutaneous lupus erythematosus but is contraindicated in pregnancy. In addition, thalidomide carries a risk for irreversible polyneuropathy; therefore, it is only advisable as a rescue therapy in patients who have failed other treatments. In atypical or refractory cases, a skin biopsy may be advisable.

Neuropsychiatric disease

Treatment is dependent on the underlying cause of the neuropsychiatric disease. If it is thought to be the result of underlying inflammation, GC and/or immunosuppressive therapy may be indicated. For embolic/ischemic/thrombotic pathophysiologies, anticoagulants/antithrombolics are advisable (Figure 4). For patients with neuropsychiatric disease that encompasses both inflammatory and embolic/thrombotic/schemic pathophysological mechanisms, immunosuppressive and anticoagulant/antithrombotic therapies may be combined.

Hematologic disease

Thrombocytopenia and autoimmune hemolytic anemia may occur in patients with SLE and require anti-inflammatory/immunosuppressive treatment. On the other hand, autoimmune leukopenia, while common, rarely requires treatment. Treatment of these conditions is detailed in Figure 4.

Comorbidities

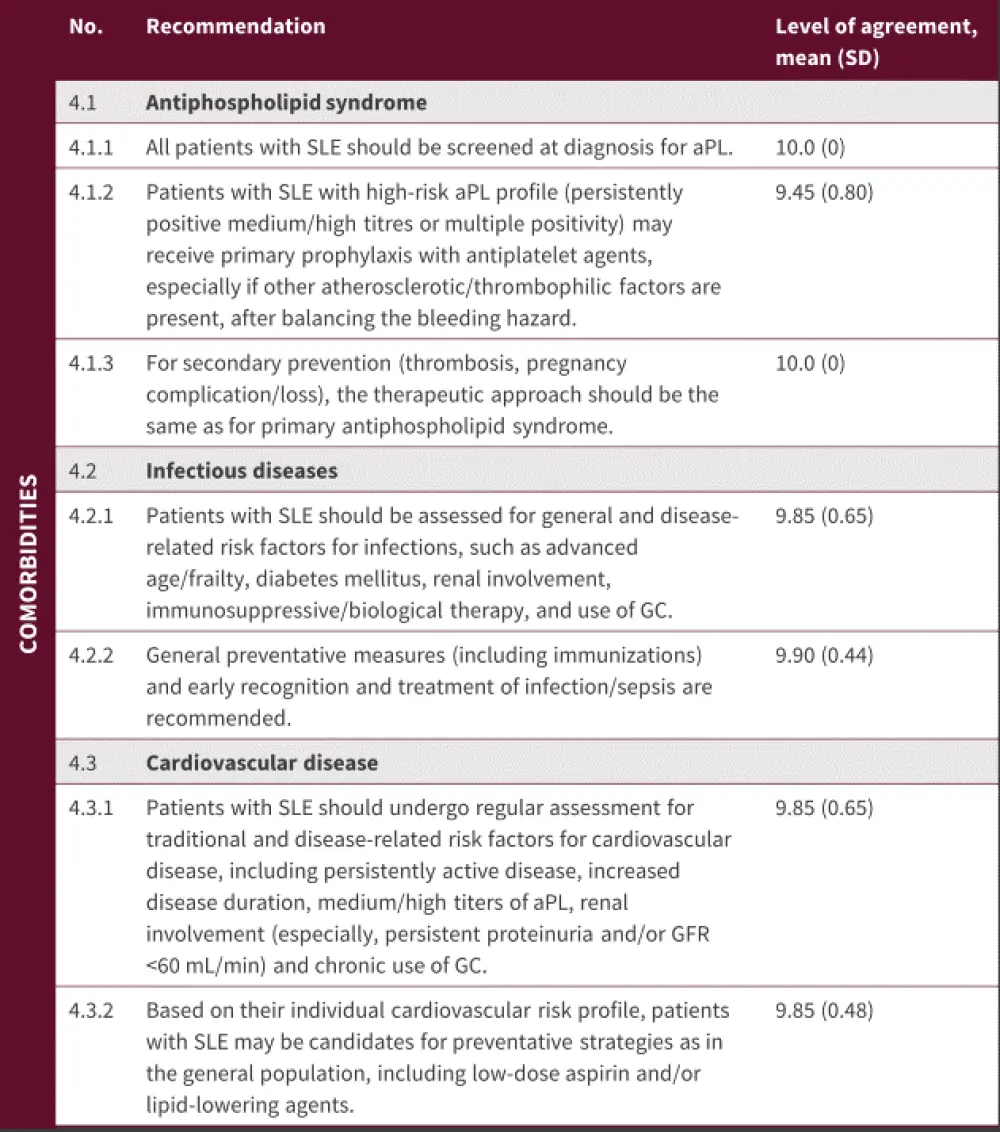

Figure 5. Comorbidities*

aPL, antiphospholipid antibodies; GC, glucocorticoids; GFR, glomerular filtrate rate; SD, standard deviation; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

*Adapted from Fanouriakis, et al.1

Antiphospholipid syndrome

Patients with SLE and carrying antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) are at risk of thrombotic and obstetric complications, which can result in increased damage build-up. Carriers of aPL with SLE may benefit from low-dose aspirin, though it is unclear whether this is effective only in those with a high-risk aPL profile. These patients may also benefit from anticoagulant treatment. Screening for aPL is recommended for all patients with SLE (Figure 5), and the guidelines suggest that treatment of antiphospholipid syndrome in the context of SLE should be the same as treatment of primary antiphospholipid syndrome.

Infections

As patients with SLE have many risk factors that predispose them to infections, prevention should be proactive, combining general preventive measures with timely recognition and treatment (Figure 5). Vaccination against seasonal influenza and pneumococcal infection are recommended for patients during stable periods, and prompt diagnosis and treatment of sepsis is essential.

Cardiovascular disease

Patients with SLE are at risk of cardiovascular disease due to multiple risk factors, as listed in Figure 5. Statins may be used in patients with SLE based on their lipid levels and the presence of other traditional risk factors.

Update on ongoing trials

Anifrolumab, a monoclonal antibody against the type I interferon receptor subunit 1, has been investigated for the treatment of general extrarenal SLE in two phase III randomized control trials called TULIP-1 and -2.3

Using the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG)-based Composite Lupus Assessment (BICLA) system in the TULIP-1 trial, patients treated with anifrolumab showed an improved response rate compared with the placebo. However, the study failed to meet its primary endpoint, the SLE Responder Index (SRI)-4. BICLA includes partial responses and gives greater weight to skin symptoms over joint disease compared with SLEDAI-based SRI.

A BICLA response was recorded in 47.8% of patients treated with anifrolumab compared with 31.5% in the placebo group in the TULIP-2 trial (p = 0.001). Patients who mainly had skin disease seemed to benefit the most from treatment with anifrolumab, which allowed a decrease in GC treatment. There was an increase in herpes zoster in patients treated with anifrolumab compared with placebo (7.2% vs 1.1%, respectively) but all cases were cutaneous and resolved without cessation of therapy.

Conclusion

Management of patients with SLE continues to be challenging, with the myriad of disease presentations along with patient risk factors and comorbidities adding to the challenge. The EULAR 2019 guidelines provide current recommendations for clinical practice; however, they act only as a snapshot in time so will require regular updating. The results of the TULIP-1 and -2 trials may feature in the next version of the guidelines, with anifrolumab being added to earlier lines of therapy for patients with SLE.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content