All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The lupus Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lupus Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lupus and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lupus Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported through a founding grant from AstraZeneca. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lupus content recommended for you

Neuropsychiatric manifestations in early vs late-onset SLE: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is more common in women of childbearing age, while late-onset SLE (ltSLE) is more prevalent among males. In older patients, the diagnosis of neuropsychiatric SLE is challenging due to polypharmacy and multiple comorbid conditions affecting the central nervous system.

Some models have been developed previously for the attribution of neurological symptoms to SLE; however, they lack specificity to ltSLE patients. Pamuk et al.1 recently conducted a systematic literature review and meta-analysis, published in Rheumatology, to evaluate the frequency and specific clinical manifestations of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (NPSLE) in older patients with SLE. Here, we summarize the key points below.

Methods

- A literature search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases to identify relevant studies published between 1959–2022.

- A forest plot was used to compare odds ratios of NPSLE incidence and manifestations across age groups. Pearson’s correlation test was used to determine associations between the presence of autoantibodies and clinical manifestations.

- The SLE cohorts were categorized as:

- Early-onset SLE (eSLE): SLE diagnosed at <50 years of age

- Childhood-onset SLE: SLE diagnosed at <18 years of age

- LtSLE: SLE diagnosed at ≥50 years of age

- Early-onset SLE (eSLE): SLE diagnosed at <50 years of age

Key findings

- Out of 2,438 search results, 44 studies met the eligibility criteria, involving a total of 17,865 eSLE and 2,970 ltSLE patients. Central nervous system involvement was identified in 3,326 patients (2,955 eSLE and 371 ltSLE).

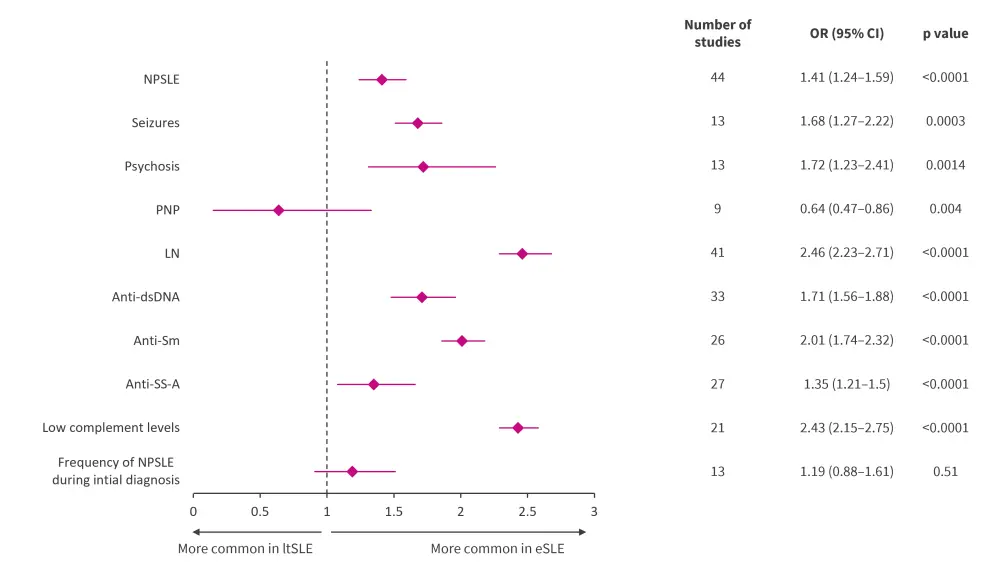

- Compared with the ltSLE group, the eSLE cohort had a significantly higher frequency of cumulative NPSLE, seizures, psychosis, lupus nephritis, anti-dsDNA, anti-Sm, anti-SS-A, and hypocomplementaemia. However, peripheral neuropathy was more common in the ltSLE group (Figure 1).

- The frequency of NPSLE did not differ between the eSLE and ltSLE groups at the time of initial diagnosis of SLE (Figure 1).

- In the eSLE group, the frequency of antiphospholipid syndrome was negatively associated with peripheral neuropathy (r = –0.84, p = 0.017). The presence of lupus nephritis was associated with hypocomplementaemia (r = 0.55, p = 0.015); however, there was no association between autoantibodies, hypocomplementaemia, and the clinical manifestations of NPSLE in either group.

- NPSLE was more frequent in childhood-onset SLE patients compared with the ltSLE group (odds ratio [OR], 1.53, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.16–2.01; p = 0.0025), but did not differ significantly compared with the eSLE group (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.82–1.16; p = 0.74).

Figure 1. Neuropsychiatric manifestations in early- vs late-onset SLE*

Anti-dsDNA, anti-double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid; Anti-Sm, anti-Smith; Anti-SS-A, Anti-Sjogren's Syndrome; CI, confidence interval; eSLE, early-onset systemic lupus erythematosus; LN, lupus nephritis; ltSLE, late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus; NPSLE, neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus; PNP, peripheral neuropathy; OR, odds ratio; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

*Data from Pamuk, et al.1

|

Key learnings |

|

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content