All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The lupus Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lupus Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lupus and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lupus Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported through a founding grant from AstraZeneca. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lupus content recommended for you

Risk factors associated with cardiovascular events in systemic lupus erythematosus

As previously reported on the Lupus Hub, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Several traditional cardiovascular and lupus-specific risk factors have been found to contribute to risk of cardiovascular events (CVE) in patients with SLE. Understanding this relationship is crucial to effectively manage cardiovascular risk.

Results of previous studies investigating factors associated with CVE in SLE are highly variable, this may be attributed to differences in study design, study population, number of centers included, and duration of follow-up.

To bridge the knowledge gap, Farina et al.1 recently published an article in Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism analyzing cardiovascular risk factors and SLE-specific factors associated with CVE in patients with SLE in a large, monocentric, ethnically diverse cohort of patients with long term follow-up.1 Below, we summarize the key findings.

Methods1

This observational retrospective study analyzed data from medical records of patients treated between 1979 and 2020 at the Lupus Clinic at University College London Hospital. Patients meeting the American College of Rheumatology revised classification criteria for SLE and having complete information on the start and end of follow-up, including occurrence and year of CVE, data regarding demographic and disease features, treatment history, and traditional cardiovascular risk factors, were included.

Regression analyses were used to test the association of all risk factors with CVE.

Results1

A total of 419 patients with SLE were included in the analysis. Median age at diagnosis was 31 years (Interquartile range [IQR], 23–40), 91% of patients were female, and 57% were Caucasian. Patients were followed up for a median duration of 13 years (IQR, 9–18) for up to 40 years.

Overall, 71 (17%) patients experienced at least one CVE, with instances of venous thromboembolic events (VTE; 50%), cerebrovascular attacks (CVA; 32.5%), and coronary artery disease (CAD; 17.5%). Mean age at CVE was 44 years (standard deviation [SD], 12), mean disease duration was 10 years (SD, 7), and median time from diagnosis to CVE was 8 years (IQR, 4–15).

Patients with CVE had a significantly higher prevalence of hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, and antiphospholipid antibody (aPL) positivity, and less frequent use of hydroxylchloroquine compared with patients without CVE. A descriptive comparative analysis of the demographic and disease characteristics of the study population is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Disease characteristics and cardiovascular risk factors of the study population*

|

Anti-dsDNA, anti-double-stranded DNA antibody; aPL, antiphospholipid antibody; CVE, cardiovascular event; IQR, interquartile range; SDI, Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics Damage Index score; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus. |

|||

|

Variable, % (unless otherwise stated) |

Patients who did not have CVE (n = 348) |

Patients who had CVE (n = 71) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Median age at diagnosis (IQR), years |

30 (22–39) |

33 (25–41) |

0.076 |

|

Female |

92 |

87 |

0.246 |

|

Ethnicity |

|||

|

Caucasian |

55 |

66 |

0.087 |

|

South Asian |

18 |

14 |

0.415 |

|

African/Caribbean |

24 |

16 |

0.123 |

|

Other |

3 |

4 |

0.549 |

|

Raised BMI† |

46 |

51 |

0.462 |

|

Ever smoker |

28 |

35 |

0.240 |

|

Hypertension |

34 |

39 |

0.306 |

|

Hypercholesterolemia |

28 |

41 |

0.035 |

|

Diabetes |

4 |

10 |

0.027 |

|

Lupus nephritic |

33 |

38 |

0.428 |

|

Anti-dsDNA positivity |

53 |

66 |

0.653 |

|

Decreased C3 |

45 |

48 |

0.714 |

|

aPL positivity |

27 |

58 |

<0.001 |

|

Use of hydroxylchloroquine |

89 |

80 |

0.049 |

|

Median SDI (IQR) |

0 (0−1) |

1 (0−2) |

0.123 |

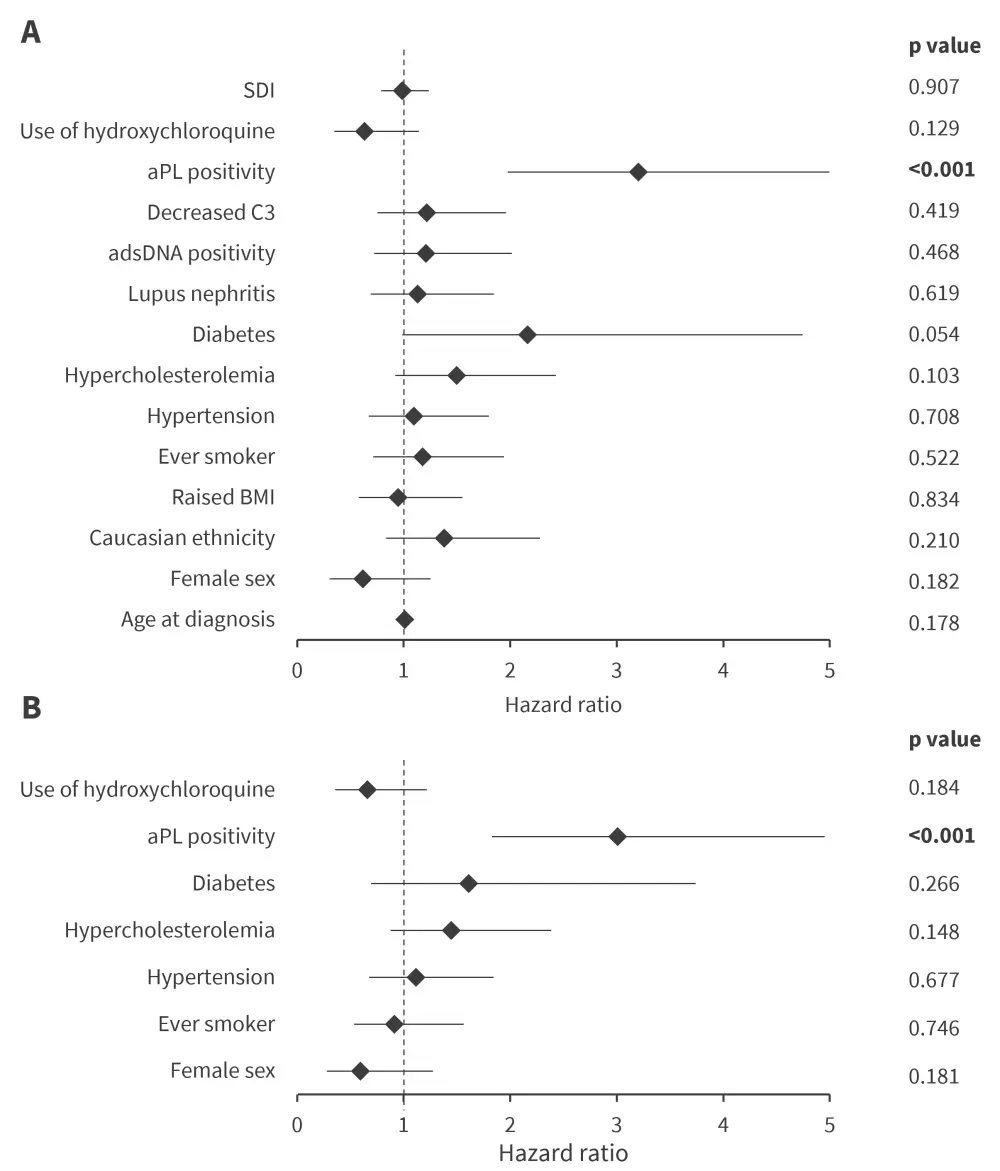

In univariable Cox proportional hazards analysis, a significant association was found between aPL positivity and CVE; however, the remaining variables did not exhibit significant associations (Figure 1A). Among aPLs, either lupus anticoagulant (22%) or anti-cardiolipin antibodies (26%) were significantly associated with CVE (p < 0.001).

The multivariable Cox proportional hazards model further confirmed aPL positivity to be the sole factor significantly associated with CVE (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Association between independent variables and CVE using A univariable and B multivariable Cox regression analysis*

aPL, antiphospholipid antibody; adsDNA, anti-double-stranded DNA antibody; BMI, body mass index; CVE, cardiovascular event; SDI, Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics Damage Index score.

*Data from Farina, et al.1

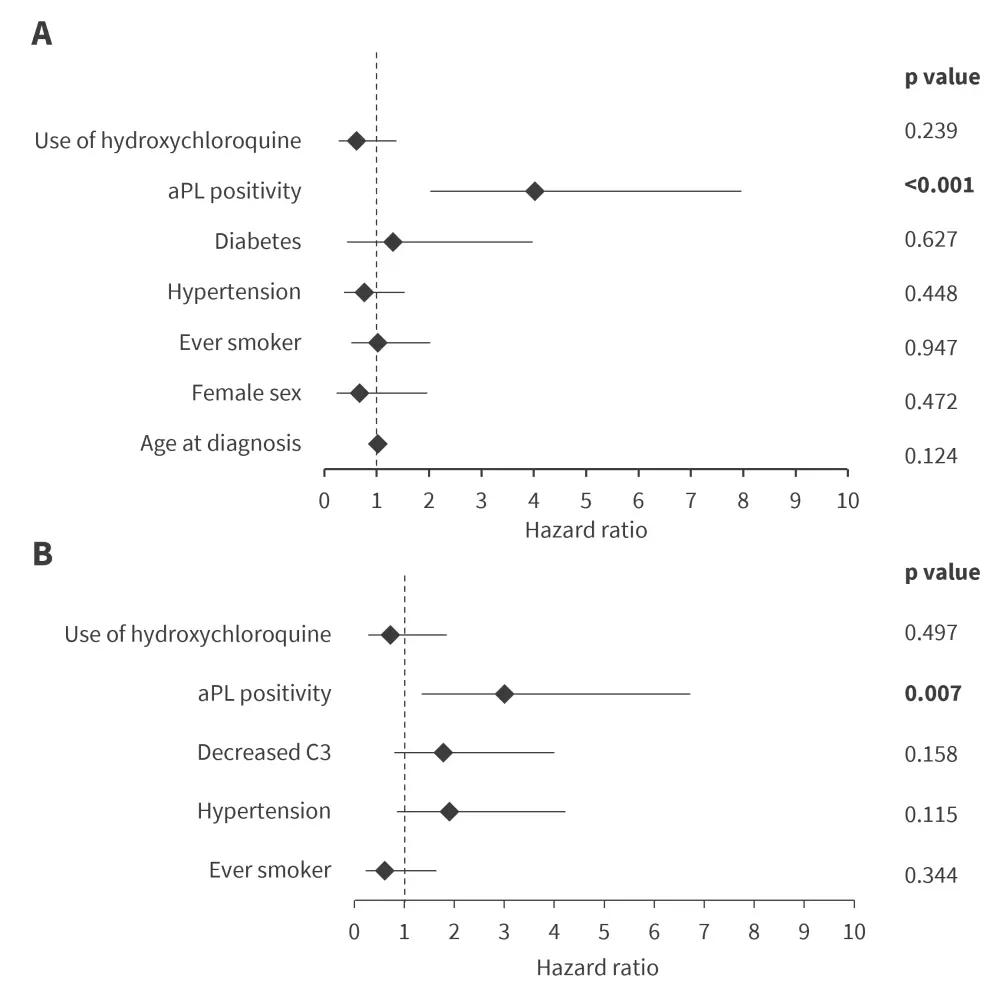

While analyzing for different types of CVEs using multivariable Cox regression, only aPL positivity was found to be significantly associated with both VTE and CVA (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Multivariable Cox regression analysis of association of independent variables with A VTE and B CVA*

aPL, antiphospholipid antibody; CVA, cerebrovascular attack; VTE, venous thromboembolic event.

*Data from Farina, et al.1

In a subgroup of 212 patients with available data on cumulative dose of glucocorticoids, Cox regression analysis revealed a significant association between glucocorticoid cumulative dose and CVE (hazard ratio [HR] per 1,000 mg, 1.029; 95% confidence Interval [CI], 1.008–1.050; p = 0.006).

Additionally, SLE diagnosed before 2000 demonstrated strong association with adverse cardiovascular outcome (HR, 4.39; 95% CI, 2.64–7.28; p < 0.001).

Among the traditional cardiovascular risk factors, Log-rank test revealed significant association between diabetes and CVE (p = 0.046), albeit observed in a small number of patients.

Conclusion1

These findings confirmed the high prevalence of CVE among patients with SLE; around one in every five patients in the study population experienced at least one CVE. The study revealed a strong association between aPL positivity and CVE, including both CVA and VTE. Additionally, glucocorticoid therapy and diagnosis of SLE before 2000 were also found to be associated risk factors.

The authors noted several limitations of this study, including its retrospective nature which did not allow identification of predictors of CVE. Additionally, time-dependent co-variates and some potentially relevant factors, such as physical exercise, could not be assessed. Finally, there’s a possibility that patients with persistent aPL positivity could have different risk to those who are positive only once.

Further, randomized clinical trials are warranted to validate the study hypothesis.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content