All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The lupus Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lupus Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lupus and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lupus Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported through a founding grant from AstraZeneca. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lupus content recommended for you

Editorial theme | Risk factors for and prevention of organ damage accrual in patients with SLE

Do you know... To date, which of the following is the only validated tool for assessing organ damage in SLE?

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease characterized by diverse manifestations and multi-organ involvement.1,2 Organ damage refers to irreversible changes resulting from a complex interplay of several factors, including the disease itself, its treatment, and comorbidities.1,3

Despite the advancements in treatment strategies for SLE, the prevention of damage accrual remains an unmet need.1 Currently the SLE clinical trials have started integrating damage as an outcome measure, as recommended by both the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the FDA.4

In this first article in our editorial theme on organ damage accrual in SLE, we explore risk factors contributing to damage and strategies for prevention.

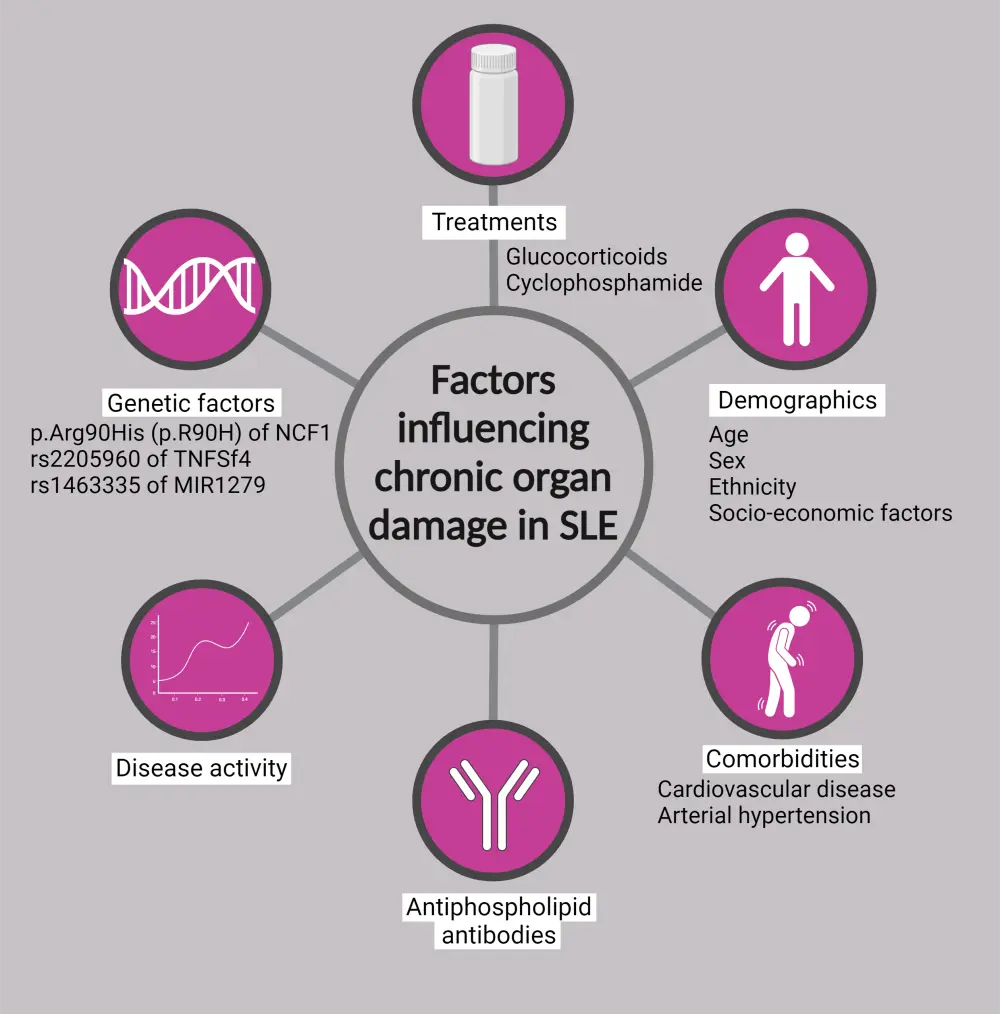

Risk factors1-5

As depicted in Figure 1, there are several contributing factors to damage accrual in patients with SLE.

Figure 1. Risk factors for chronic organ damage in SLE*

SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

*Data from Ceccarelli, et al.1 Created with BioRender.com

Disease activity1

Damage progression or accrual over time has been found to be significantly associated with disease activity, which is commonly measured by SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI), Safety of Estrogens in Lupus National Assessment-SLEDAI, British Isles Lupus Assessment Group, and Lupus Low Disease Activity State.

Antiphospholipid antibodies1

Antiphospholipid antibodies, which are detected in 31–71% of patients diagnosed with SLE, may contribute to organ damage, possibly through thrombosis and particularly in the nervous system. An association between antiphospholipid antibody-positivity and cardiovascular damage has been previously described on the Lupus Hub.

Treatments1,3

Although glucocorticoids continue to be the cornerstone of SLE management, they have been significantly associated with damage accrual.1 While certain complications related to corticosteroid therapy are reversible, such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity; others, such as avascular necrosis, osteoporotic fractures, and cataracts, constitute irreversible damage.3 Among immunosuppressants, cyclophosphamide has been associated with higher damage, particularly the development of premature ovarian failure.1

Genetic factors1

Studies have established a clear association between genetic factors and the risk of damage accrual, such as:

- p.Arg90His (p.R90H) of neutrophil cytosolic factor 1 with lupus nephritis;

- mannan-binding lectin deficiency with cardiovascular damage;

- variant rs2205960 of TNFSF4 with renal damage; and

- variant rs1463335 of MIR1279 with neuropsychiatric damage.

Demographic factors

Older age and disease duration1,3

As expected, a longer disease duration means a higher risk of damage, considering both the disease's natural progression and the impact of treatment. However, the disease duration and age at disease onset independently influence damage accrual.1,3

Sex1,3

Studies have indicated a higher influence of male sex on damage accrual, particularly in renal and cardiovascular (CV) areas.1,3 This could be due to shorter time to diagnosis and more unhealthy lifestyle behaviors among male patients.3

Ethnicity1

Afro-American ethnicity is associated with skin, renal, pulmonary, and CV damage. Other ethnicities, such as mestizos, Texan Hispanics, and Indians, also appear to have an increased risk of damage accrual.

Comorbidities1

Arterial hypertension is a common comorbidity in patients with SLE, often linked to kidney involvement. Presence of metabolic syndrome is associated with increased CV events,3 while increased homocysteine, or uric acid levels, are associated with damage progression.1

Socio-cultural background1

Uncontrolled disease, which can lead to damage, can also arise due to socio-cultural factors such as education, occupation, socioeconomic status, and access to care.

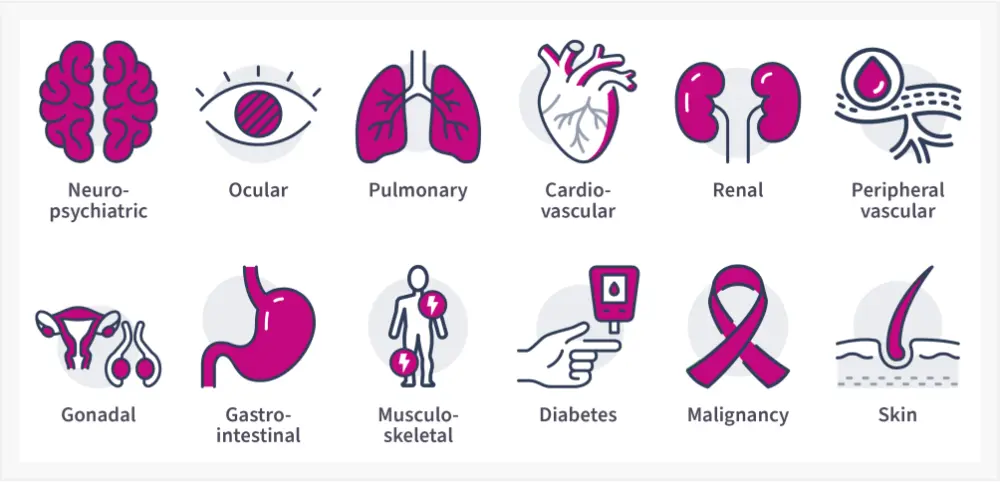

Assessment of organ damage

To date, the only validated index for evaluating organ damage in SLE is the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics Damage Index (SDI), which measures irreversible change in an organ or system persisting for ≥6 months since SLE onset.1,3 It comprises 41 items spanning 12 different organ systems, as represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Organ domains included in SDI*

SDI, Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics Damage Index.

*Adapted from Ceccarelli, et al.1

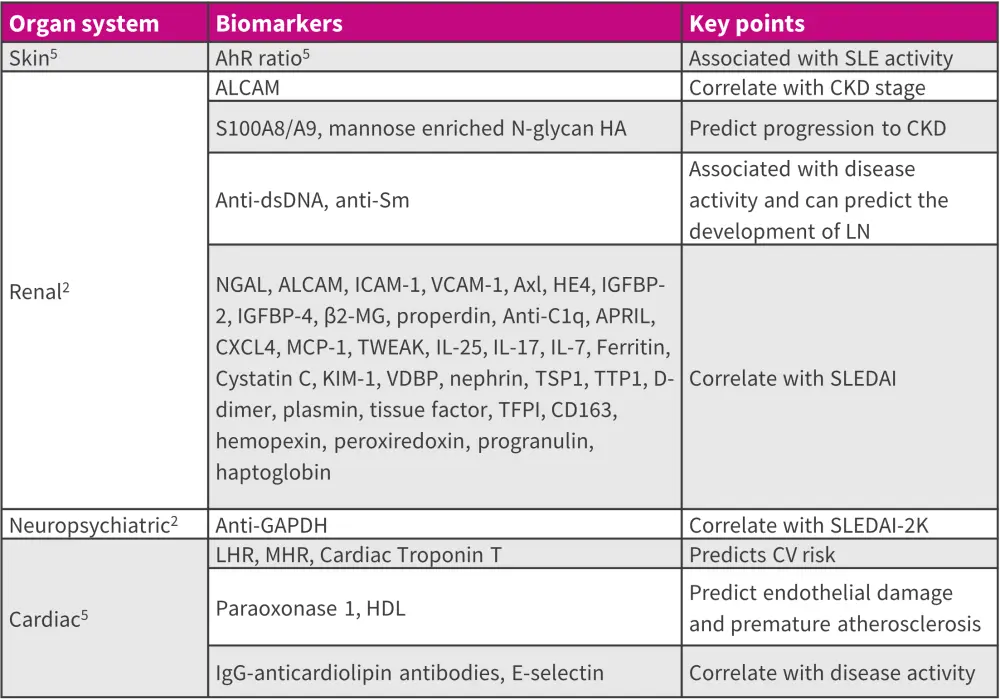

The SDI covers events after SLE diagnosis. However, organ damage could accrue in a prodromal period prior to official SLE diagnosis (Figure 3).4 With acknowledgment of the limitations of the existing SDI, an international collaboration is in progress between Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics, the Lupus Foundation of America, and the American College of Rheumatology to update the SDI.4

Figure 3. Disease onset and subsequent organ damage accrual*

SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SDI, Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics Damage Index.

*Adapted from Barber, et al.4

Based on the SDI, two patient self-administered tools were developed, namely the Lupus Damage Index Questionnaire (LDIQ) and the Brief Index of Lupus Damage (BILD).3 Recently, a new outcome has been proposed, the Lupus Comprehensive Disease Control (LupusCDC), a condition defined by the achievement of remission and the absence of damage progression.1

The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology/American College of Rheumatology criteria to assess organ damage in patients with SLE and lupus nephritis has been previously published on the Lupus Hub.

Prevention and treatment

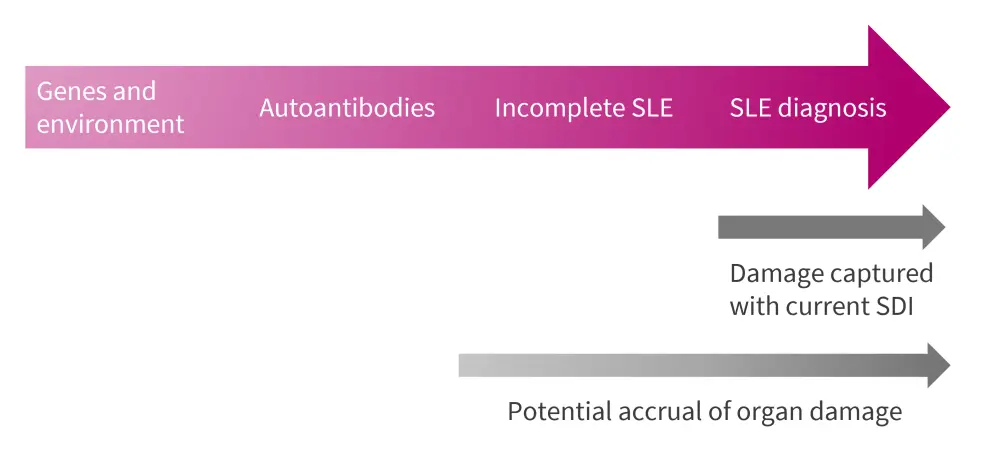

One critical aspect in the management of SLE is the identification of reliable biomarkers for early diagnosis, and for monitoring disease activity and prognosis.2 The key biomarkers for the commonly affected organ systems in SLE are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Biomarkers associated with organ damage in SLE*

AhR ratio, ratio of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in Th17 cells to that in Treg; ALCAM, activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule; ANA, antinuclear antibody; APRIL, a proliferation inducing ligand; BAFF, B lymphocyte activating factor; CLE, cutaneous lupus erythematosus; DNase I, deoxyribonuclease I; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; Gas6, Growth arrest-specific protein 6; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; ICAM, intracellular adhesion molecule; IGFBP, insulin-like growth factor binding proteins; Ig, immunoglobulin; IL, interleukin; KIM, kidney injury molecule; LHR, low-density granulocytes-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio; MHR, monocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein; SLEDAI, SLE Disease Activity Index; TWEAK, tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; Sm, Smith; Treg, T regulatory cell; TFPI, tissue factor pathway inhibitor; VGLL3, vestigial like family member.

*Adapted from Ding, et al.2 and Yu, et al.5

The treat-to-target recommendations by the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology, as previously published on the Lupus Hub, emphasize achievement of remission or low disease activity to prevent chronic organ damage accrual.1,4

Additionally, given the beneficial effects of antimalarials in preventing disease flares, reducing corticosteroids use, and positively influencing various metabolic risk factors, these should be used in patients with SLE unless contraindicated.3 Further, novel treatments with better disease control and corticosteroid-sparing properties, such as belimumab, are clinically beneficial in protecting patients with SLE from damage accrual.3

Conclusion

Given the multifactorial etiology of SLE, several factors contribute to damage accrual. Recognizing non-modifiable factors (age, gender, ethnicity, and genetics) can identify those at risk for aggressive disease. Addressing modifiable factors (corticosteroids, disease activity, and hypertension) involves appropriate treatment of comorbidities and lifestyle adjustments.1,3

Implementing a multidimensional approach that emphasizes early diagnosis and appropriate management strategies to prevent flares, control disease activity, and minimize corticosteroid usage can significantly reduce the onset of damage.1,3

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content