All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The lupus Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lupus Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lupus and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lupus Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported through a founding grant from AstraZeneca. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lupus content recommended for you

Considerations for family planning in female patients with lupus

Do you know... What is the relative frequency of preterm birth in pregnant patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) compared with those in the general population?

The occurrence of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is notably higher in female patients of childbearing age. Despite advancements in the management of pregnancies with SLE, a higher risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes persists when compared with the general population.1

Here, we provide an overview of the potential impact of pregnancy on SLE and vice versa, risk factors for adverse maternal and fetal outcomes, the importance of preconception counseling, and drug compatibility during pregnancy in patients with SLE.

Impact of pregnancy on SLE

Disease flares

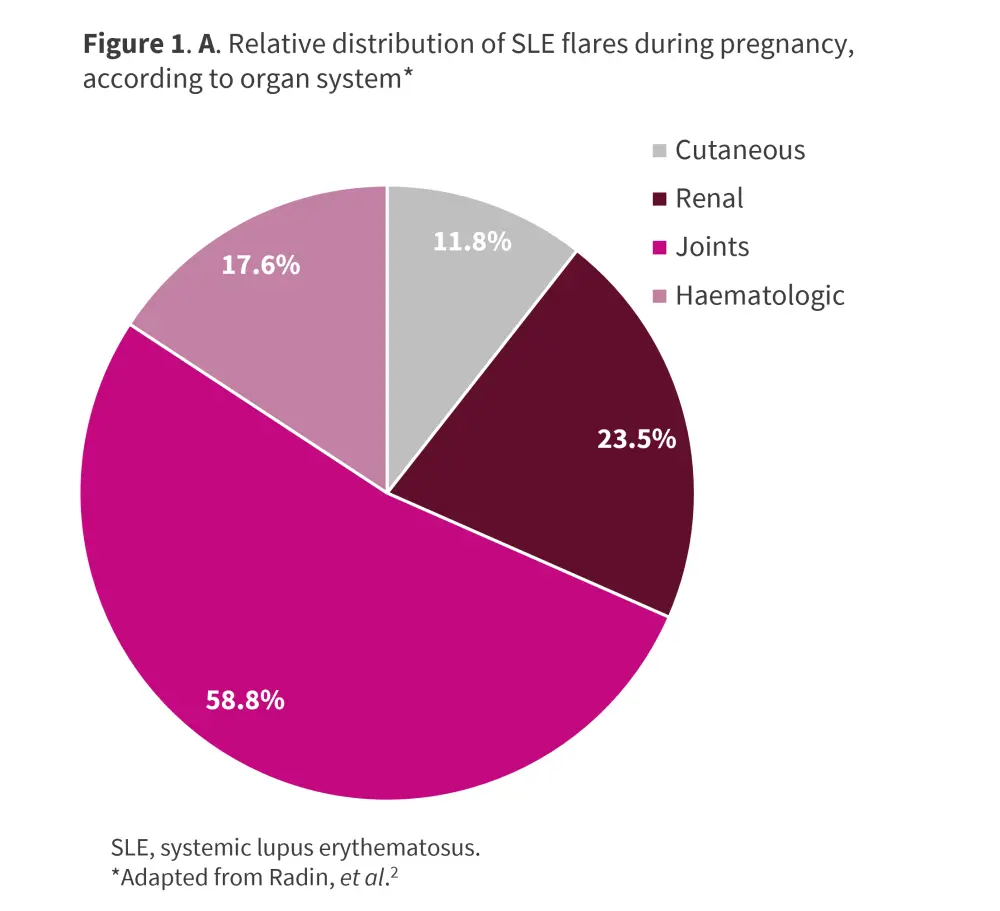

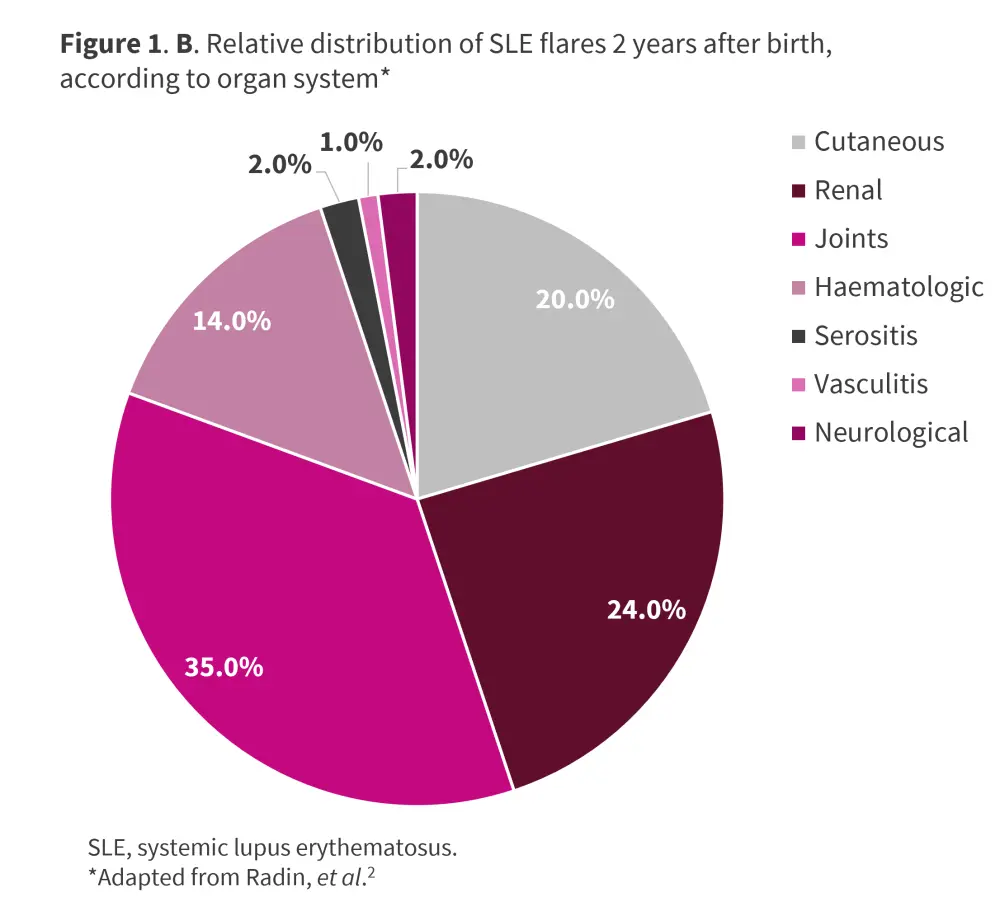

SLE typically follows a relapsing-remitting course, with flares manifesting at any point postpartum or during pregnancy; rates range between 25% and 70%. The most frequent manifestations include arthritis, hematologic, and skin-related symptoms.1 A multicenter, retrospective study conducted by Radin et al.2 in 119 pregnant patients with SLE evaluated disease activity at conception and predicted lupus flare up to 2 years after birth. At 2-year follow-up, 51.3% of patients had ≥1 flare after birth, with a mean of 0.94 flares per patient, and a median time to first flare of 9 months from birth. The most frequent flare manifestations were joint involvement, renal, cutaneous, and hematologic (Figure 1). The details of the study can be found here.

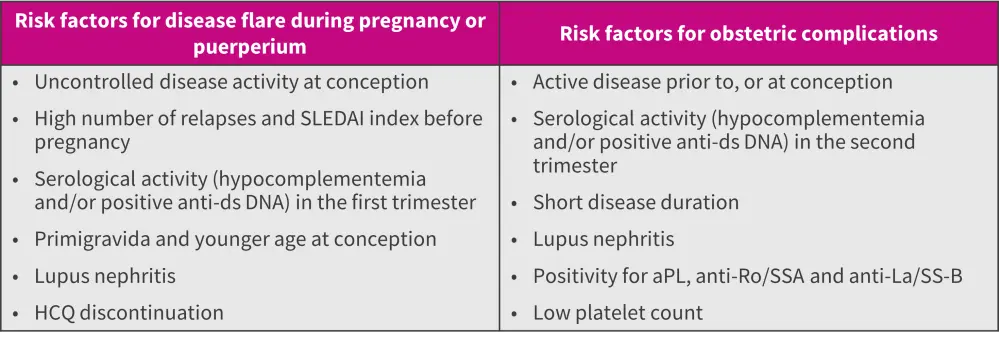

Several risk factors for flare during pregnancy have been identified (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Risk factors for SLE flare and pregnancy complications*

aPL, antiphospholipid antibodies; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; ds, double-stranded; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SLEDAI, SLE Disease Activity Index.

*Adapted from Zucchi, et al.1

Lupus nephritis1

During pregnancy or postpartum, diagnosis of new lupus nephritis (LN) was reported in 4–30% of patients with SLE; those with a previous history of LN carried a 20–30% risk of experiencing relapse during their pregnancy.

Impact of SLE on pregnancy

Infertility3

The existing literature highlights that women with SLE struggle to conceive. Furthermore, there is an increased likelihood of miscarriage and pregnancy-related disorders influenced by immunological factors, such as the presence of anticardiolipin antibodies.

Maternal outcomes

Preeclampsia

Preeclampsia affects up to 30% of SLE pregnancies compared to 3.4% of all pregnancies in the United States.2 Risk factors of preeclampsia in female patients with SLE include renal involvement, thrombocytopenia, and antiphospholipid antibody (aPL) positivity.1

Emerging evidence suggests that natural killer (NK) cells play a pivotal role in maintaining a pro-inflammatory microenvironment in the decidua of healthy pregnancies. Inadequate activation of NK cells leads to poor decidual artery remodeling and increases the risk of preeclampsia. Hence, the presence of NK cells and endothelial progenitor cells in the blood may serve as biomarkers for early diagnosis of preeclampsia.3

Hypothyroidism3

Thyroid disease is more prevalent in pregnant patients with SLE compared with those in the general population. In addition, hypothyroidism and auto-immune thyroid disease, characterized by the presence of thyroid antibodies with or without thyroid dysfunction, are common in female patients with SLE.

Neurological symptoms3

SLE can affect the central nervous system, with manifestations ranging from headache and cognitive impairment to life-threatening conditions, such as memory loss, seizures, and stroke. While stroke and transient ischemic attacks are less common in SLE, the presence of aPL antibodies is believed to be a contributing factor to arterial and venous thrombosis.

Infection3

Given that pregnancy itself is associated with a weakened immune state, SLE increases the risk of infection in pregnant women; SLE is caused by immune system dysregulation and excessive autoantibody production.

Fetal mortality

Pregnancy loss is one of the most prevalent maternal complications, observed in around 16.5% of patients with SLE1,2; with risk factors including active disease and low complement or positive anti-double-stranded DNA in the second trimester.1

Fetal outcomes

Preterm birth

Preterm birth is one of the most common obstetric complications, affecting about 30–40% of patients with SLE compared with 12% in the general population.1

The major risk factors for preterm birth in pregnant patients with SLE include activation of the maternal or fetal hypothalamus-pituitary axis, local and systemic inflammation from infections, autoantibodies, lowered estrogen levels, and treatment with oral prednisone.3 Preterm births are more commonly observed in patients with disease activity at conception, due to increased inflammation and autoantibodies, immunological alterations, and medications.3 In addition, SLE patients have higher rates of cesarean delivery compared with the general population.1

IUGR and SGA neonate1

Studies have reported a higher incidence rate of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) in female patients with SLE compared with the general population (5.3% vs 1.6%). The incidence is highest during active disease at conception or in the 6 months preceding pregnancy. One of the major risk factors for IUGR in SLE pregnancies is the presence of aPL.

Also, the incidence rate of small for gestational age infants is reportedly significantly higher in SLE pregnancies compared with the general population (25% vs 4.5%). However, in recent years, the IUGR and small for gestational age rates have declined to 2.6% and 12.2%, respectively, reflecting improvements in SLE management during pregnancy.

Neonatal lupus syndrome

Neonatal lupus occurs due to the transplacental passage of autoantibodies, anti-Ro/SSA, and anti-La/SS-B from mother to child, usually during the second trimester of gestation.1,3

The most common manifestation of cardiac neonatal lupus is congenital heart block, which needs pacing for survival.1,3 In cases of mothers with anti-Ro/SS-A and previous children with congenital heart block, the risk increases to up to 18%.1,3 The key risk factors for obstetric complications in SLE pregnancies are listed in Figure 2.

The Lupus Hub has previously presented an expert opinion on ‘What do HCPs need to know about neonatal lupus’.

Preconception counseling1

Preconception counseling with the patient and their partner is required to prevent unplanned pregnancies, stratify the single-patient pregnancy risk, and minimize adverse pregnancy outcomes through proper education and appropriate treatment. The key objectives of a preconception visit are outlined in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Goals of preconception counseling*

*Adapted from Zucchi, et al.1

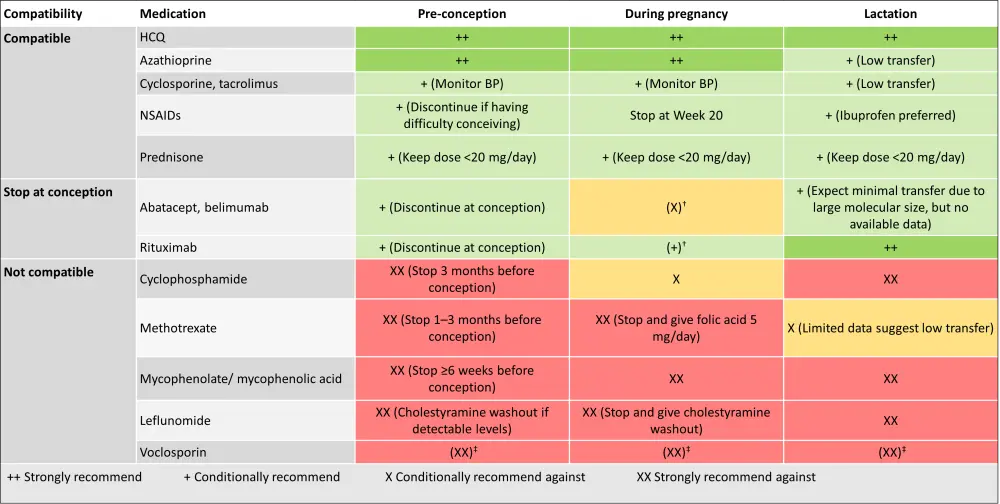

Treatment

Treatment approaches should be tailored based on patients’ disease activity, response to medication, and potential pregnancy complications. Medications, such as hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, low-dose glucocorticoids, and low-dose aspirin with or without low-molecular-weight heparin, are considered safe during SLE pregnancies; while cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and mycophenolate are contraindicated. Of note, the continuation of hydroxychloroquine during SLE pregnancies has proven effective in controlling disease activity and reducing the risk of preeclampsia, IUGR, and preterm birth. Therefore, it should not be discontinued during pregnancy as this could potentially trigger a disease flare.1

The drug compatibility during pregnancy and lactation, as per the 2020 American College of Rheumatology guidelines, are detailed in Figure 4.1,4

Figure 4. Drug compatibility during preconception, pregnancy, and lactation*

BP, blood pressure; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

*Adapted from Zucchi, et al.1; Sammaritano, et al.4

†Continuation during pregnancy should be decided on an individual basis.

‡Due to the alcohol content in the formulation.

Conclusion

Pregnant patients with SLE are at a higher risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes compared with the general population. Various risk factors have been identified, such as uncontrolled disease activity at conception, concomitant antiphospholipid syndrome or aPL positivity, and LN. Improving pregnancy outcomes in patients with SLE requires thorough preconception counseling, close clinical monitoring, and potential medication adjustments.1,3

Further studies are required to assess additional biomarkers capable of identifying those at higher risk of pregnancy complications. Additionally, the potential utilization of novel drugs in the management of SLE pregnancies needs to be investigated.

Key guidelines

- 2017 European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology recommendations for women’s health and the management of family planning, assisted reproduction, pregnancy and menopause in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus

- 2024 KDIGO guidelines for management of lupus nephritis

- 2020 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the management of reproductive health in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content